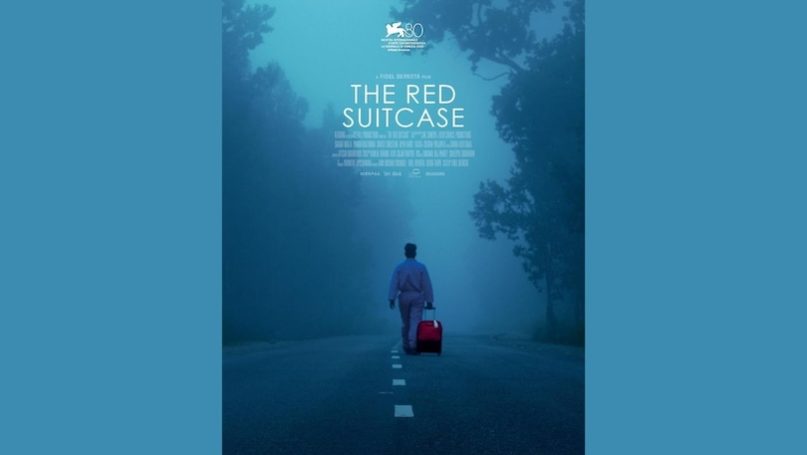

The Red Suitcase

Directed by Cyrus Neshvad, 2022

While new Iranian filmography consistently challenge orthodoxies, “The Red Suitcase” first launched in 2022, is a welcome vehicle of international protest. Iran has been rocked by civic protests confirming that a long-silenced public have reached a point of no return in their opposition to the regime. Only a ubiquitous and brutal security apparatus, and a vast secret service, is now holding the citizens of the Islamic Republic tenuously to ransom. In this brutal, secretive theocracy, women have suffered disproportionately from the callous tentacles of a moralistic police.

Their invasive networks of neighbourhood informing, effectively suffocate public life. Into this depressing theatre of moral suppression comes the positive feedback about this Oscar-nominated short film which (conversely) puts Iran in a more positive focus. For those in despair, it is a reminder that the Ayatollahs are not beyond overt international lampooning, or indeed targeted global opprobrium, on the greatest of world stages, Hollywood.

Oscar-shortlisted, “The Red Suitcase” demonstrates the potential of protest filmography to place injustices powerfully on the global agenda, It revels more in a cinematographic instant than the past torturous year of sporadic street war against the Iranian authorities. Set in Luxembourg’s airport, it tells the story of a 16-year-old Iranian girl from Tehran nervously shedding her headscarf in defiance of a medieval male dictatorship. For film director Cyrus Neshvad, born in Iran but raised in Luxemburg, his film: “exposes the virus of a regime cancerous to the beautiful body of my birth country….Once we get this virus out, the body will be flourishing again,” he told AFP. The movie includes stark photo-imagery of Iranian state repression, and a film montage of police battening retreating female protestors.

Vociferous demonstrations in Iran were sparked by the 2022 death in custody of a young Iranian woman, Mahsa Amini, detained for incorrectly wearing the headscarf mandated by religious chiefs. The scale and intensity of street rioting genuinely threatened the Islamic theocrats who took power in 1979. The Red Suitcase carries forward the momentum of the current uprising in Iran but was filmed a year before it started. Despite the cuff-holds of a ubiquitous morality brigade, Iranians felt that Mahsa must be avenged. The regime has responded by cracking down with arrests and executions – including covert intimidation of the country’s sportspeople and filmmakers. Film studios note plain-clothed police monitoring their operations, and discouragement of the fragile acting industry.

Iran’s Oscar-nominated protest filmography has its roots in the injustices faced by the director’s own family – who as Bahais are systematically persecuted in Iran. Cyrus also directly identifies among his own relatives the neurosis and angst long experienced by Iranian girls and women. Amini’s catastrophic death has again brought these patriarchal injustices to global attention. As Neshvad notes: “women in Iran being under domination of the man…If a woman wants to do something, or go visit something, the man (her father or husband) has to consent and write the paper and sign it…For the girl in my film to take her veil off…was a moment of courage…for her to rebel against a path forced upon her, but also to inspire those watching….It will be a message: ‘Follow me – like me, take your hijab off, don’t accept this domination, and let’s be free, at least have the free will to decide.”

Leading actress of “The Red Suitcase”, Nawelle Evad, 22, is French-Algerian, and herself protests the issue of women and Islamic headscarves – and the debate in the West around them. “I had a Muslim upbringing and I used to wear it,” she told AFP in Paris. “That’s what I find so beautiful in this film… the doubts that anybody, in any country, in any culture, faces… What do I choose for myself? Do I listen to my family? Am I making my own choices?” There is also an implicit word of criticism for the west too in the movie.

Neshvad’s French scriptwriting partner, Guillaume Levil, also suggested that the sexualised airport advertisements in the film exploit women. The final image of the film, an ad showing a blonde model is emblematic of both social diktats. The director notes “The closer we go with the camera on her face, slowly we see that she’s not happy, and when we are very, very close, we see that (she) is even frightened….And with this, I wanted to finish the movie. So (we criticize) not only one side, but both sides.”

The Iranian regime systematically discriminates against women, engages in violence and sexual exploitation of girls; jails, flogs women, and even conducts extra-judicial killing —for ‘crimes’ like appearing in public without head covering. It harasses activists for women’s rights; forcibly segregates women from men; disproportionately punishes women in the judicial system; denies women political and economic opportunities; and favours men over women in family and inheritance law. Islamic head covering is violently enforced by the regime. Since shortly after the 1979 Islamic Revolution, the Iranian regime has mandated those women and girls above the age of nine wear a hijab (Islamic head-covering) in public. The government has brutally crushed protests against the requirement.

Iran’s Islamic Penal Code states: “Women, who appear in public places and roads without wearing an Islamic hijab, shall be sentenced to ten days to two months’ imprisonment or a fine of fifty thousand to five hundred [thousand] Rials,” (Article 638). The article also authorizes a sentence of “two months in prison or up to 74 lashes” for “[anyone] who openly commits a harām (sinful) act, in addition to the punishment provided for the act.” Women who fail to wear headscarves and other attire covering their bodies in public may be harassed by the “Morality Police” (MP), detained, fined, and/or flogged. Many Iranians have expressed opposition to mandatory hijab, including through the “White Wednesdays” campaign (begun in 2017), in which Iranians wear white clothing in street protest. Videos of these acts of defiance by women dubbed “The Girls of Revolution Street” have gone viral worldwide. In response, President Ebrahim Raisi has only sharply increased enforcement of the hijab.

The arrest and state murder of Mahsa Amini appears all the more poignant in the light of the Oscar nomination of The Red Suitcase. It is important to note the forensic pathology of these tragic events. On September 13, 2022, the Morality Police arrested 22-year-old Kurdish Iranian Mahsa Amini in the street in Tehran while she was visiting the city with her family. They dragged her from her family and told Amini’s brother that they were detaining her for “improper” hijab and taking her to an “educational and orientation class.”

The police threw her into a van and, according to eyewitnesses, beat her to death in the vehicle while en route to the police station. It is suggested the police fabricated the crime-scene to make it appear she had collapsed with a cardiac arrest. The recovered corpse was so badly bruised her coffin had to be closed. Thousands of Iranians across the country have taken to the streets to protest against the regime after Amini’s death. Ever since this brutal action, public demonstrations have chanted “Women, life, freedom,” “Death to Khamenei,” “Death to the dictator.”

Women are increasingly going outside without a hijab, with some publicly removing and even burning their hijabs. The regime promptly arrested the female journalist who drew attention to Amini’s death (Niloufar Hamedi). She spent a period in solitary confinement at the notoriously brutal Evin Prison, and lives in daily risk of further state action. There is a flicker of hope that the prominence of The Red Suitcase at major film festivals, including the resonating buzz of favour at the Oscars, may force the religious leaders to ameliorate the worst excesses of police brutality. Recently there has been an unprecedented mass pardoning of street protestors.

However, it would be naïve to hope that this embattled regime is capable of genuine change. As The Red Suitcase shows, the only conceivable option for the lucky few, is escape. Like the girl in this Oscar-nominated movie, the makers had to flee Iran in order to genuinely express themselves. If there is to be a new and indigenous Iranian filmography of protest, it is likely to be sustained by expatriates rather than by indigenous film-crews. Nevertheless the unprecedented success of The Red Suitcase, one of few Iranian movies short-listed for an Oscar in recent memory, demonstrates the potential of cinematography as a vehicle of protest against a corrupt, brutal theocracy.