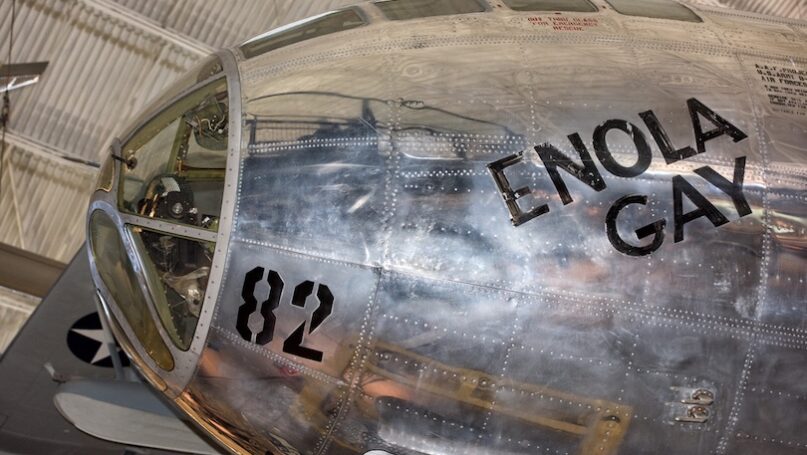

In the last days of the Second World War, on the 6th and 9th of August 1945, the United States deployed nuclear bombs against the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. This first and only use of nuclear weapons in the history of warfare proved to be highly destructive; the exact number of fatalities is a matter of debate, but estimates range between 130,000 and 230,000 people – roughly half of whom were killed at the time of the explosions, while the other half perished in the subsequent months from the injuries they suffered during the events, primarily severe burns and radiation sickness. Despite the US government’s argument that the nuclear bombings effectively brought an end to WWII (Japan surrendered on 15 August 1945) and saved hundreds of thousands or even millions of lives – American and Japanese – the fact that the overwhelming majority of victims were civilians continues to make the ethical and legal justification for the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki a matter of sharp controversy. What receives far less attention but proves equally contentious are the strategic considerations of the United States’ political and military leadership at the time and, ultimately, the question whether the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was justified from a strategic perspective.

The Unites States was the first – and only – country to deploy nuclear bombs against another country during war. As such, the US leadership had no means to make recourse to experience and historical evidence regarding the political and military effects of deploying nuclear bombs against enemy population centres and military bases. To navigate these uncharted waters, the US leadership developed certain assumptions about the probable political and military impacts of such an act. The two main expectations were that it would shock the Japanese leadership into surrender, and that it would at the same time intimidate the Soviet Union’s leadership.

Numerous factors indicate the US leadership’s conviction that the severe destruction of entire cities through the use of single pieces of ordnance would seriously “shock and awe” the Japanese political and military leadership, which, by the end of the war, primarily consisted of Emperor Hirohito as the formal head of state, as well as the Supreme War Council, an inner cabinet consisting of the six ministers most directly involved in military affairs. The destruction caused by the nuclear bombs would be so demoralising that it would clearly demonstrate to the Japanese leadership the unquestionable military superiority of the United States, crush their morale and make them realise the futility of their resistance.

While bringing an end to the Pacific War was almost certainly the main justification for the deployment of atomic bombs, there is evidence that Washington also assumed that the destructive effects of such an unprecedented event would highly impress the Soviet government (Walker 2001, 70), who’s communist doctrine stood diametrically opposed to the United States’ notion of a liberal, capitalist world order – a bitter fault line that constituted the foundation of the upcoming Cold War. The US government had predicted this impending confrontation. In the three months between Nazi Germany’s unconditional surrender on 8 May 1945 and the nuclear bombings in Japan, the Soviet Union occupied the areas it had liberated, including all of Eastern Europe as well as crucial parts of Central Europe. It soon annexed parts of the former, including them into the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), while the remaining regions under Soviet control were turned into socialist satellite states. This development caused major concern among Washington and its western allies. Sending a strong signal to Moscow that the United States had an enormously powerful weapon at its disposal, it was assumed, would intimidate the Soviet leadership. Demonstrating the US government’s capability and resolve to inflict enormous destruction to anybody who threatened its core interests would give the United States significant diplomatic leverage, thereby furthering US geo-strategic interests (Alperovitz 1965).

The United States, provoked by Japan with the surprise Attack on Pearl Harbor, was paying a tremendous price in lives and money to defend its interests and retaliate against Japanese aggression. While its geography and military power protected the American people from the large-scale destruction of civilian and industrial infrastructure, the financial and emotional burden that was placed on US society was nevertheless immense. The US government pictured the nuclear bombing of Japanese cities as a way of ensuring that the home front would not collapse before victory against Imperial Japan was achieved.

The covert efforts to develop nuclear weapons, code named “Manhattan Project,” cost the US tax payer close to USD 2 billion (Hewlett and Anderson 1962, 723) – a significant amount of money for the US treasury. James F. Byrnes, a close ally of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, warned the latter that “if [the nuclear bomb] proves to be a failure, it will be subjected to relentless investigation and criticism” (Bernstein 1995, 135). Contemporary treasury experts, however, calculated that the spending for the Manhattan Project “represents the cost of less than nine days of war” (Edmonton Journal 1945, 1). Indeed, even if the nuclear bombs would have failed to detonate, by the time of their deployment the US government was certain that Japan had no chance of winning the war. Emerging victorious from WWII and becoming one of the world’s most powerful nations, it is doubtful if the US government would get into serious trouble about a failed military project.

Far more so than government spending, the devastating Japanese surprise Attack on Pearl Harbor enraged many Americans. This, in addition to the Pacific War’s high toll in blood and highly publicised Japanese war crimes against US soldiers, led to increasing anti-Japanese resentment and at times outright racism among large parts of the US population throughout WWII. After years of public dehumanisation of the enemy, many Americans, including many members of its political and military leadership, felt little empathy for the suffering of Japan’s civilian population. According to historian James Weingartner (1992), “the widespread image of the Japanese as sub-human constituted an emotional context which provided another justification for decisions [to use nuclear weapons against Japan] which resulted in the death of hundreds of thousands” (67). The American public largely welcomed the nuclear bombings, particularly as they were commonly associated with the defeat of Japan.

The inevitable clash between East and West looming at the horizon, the great powers began to jockey for position immediately after the defeat of Nazi Germany. Moscow’s control over Eastern Europe brought the United States in a difficult strategic position, impeding its efforts to contain the Soviet Union’s global influence. The US government therefore hoped that the nuclear display of power would improve its negotiating position against the Soviet Union regarding a growing number of concerns, particularly the post-war order in Europe, as “the possibility of using America’s nuclear advantage in the short run to secure other goals naturally appealed to politicians frustrated by what they regarded as Russia’s obstructive behavior” (Maddox 2001, 61). Far from achieving this objective, however, the Soviet leadership turned out to be hardly intimidated by the deployment of nuclear bombs against Japan. Instead, Stalin grew determined to speedily develop Soviet nuclear weapons to counter the US threat, and the United States gained little diplomatic leverage in the negotiations about Eastern Europe’s fate as it had to accept the uncomfortable realities that the Red Army had created on the ground.

The American government’s geopolitical interests were not limited to Europe. Eager to establish the United States as the dominant power in the Pacific and Southeast Asia, Washington soon realised that Imperial Japan’s collapse and withdrawal from these regions would open up spheres of influence that not only the United States wanted to fill. The experience of Soviet expansionism in Eastern Europe fresh on its mind, the US government was determined to limit the Soviet Union’s eastern expansion of its sphere of influence as much as possible.

Despite being in opposite camps, both Tokyo and Moscow had far more pressing concerns than each other and in 1941 signed a non-aggression pact. However, by mid-1945 the Soviet Union’s concerns had largely been addresses, and, the neutrality agreement notwithstanding, the US government “anticipated Moscow’s intervention in mid-August, but the Soviets moved up their schedule to August 8, probably because of the Hiroshima bombing” (Bernstein 1995, 149). However, the date of the Soviet invasion of Manchuria was not necessarily influenced by the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima – it happened precisely three months after Germany’s surrender on 8 May 1945 (9 May, 00:43 Moscow time), exactly as Stalin had previously assured his western Allies. The Soviet leadership was likely eager to get combat operations against Japan started quickly to extract gains in the Far East before the inevitable surrender of Japan and the cessation of hostilities. Washington was keen to hamper this aspiration and, believing that the nuclear bombing of Japanese cities would shorten the Pacific War, destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki at least partially with the intention to advance its strategic objectives in the Pacific region.

The primary strategic objective of the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was undoubtedly the defeat of Japan, thereby bringing an end to WWII. The US leadership wanted the war to end quickly – particularly before the Soviet Union was ready to launch an amphibious invasion of Japan – but, at the same time, hoped that Japan’s unconditional surrender would be secured without a costly American invasion of the Japanese home islands.

Often named the single most decisive encounter in the Pacific theatre, the Battle of Midway constituted the turning point of the war between Japan and the United States. In the following three years, the US military and its allies conquered almost all of Japan’s strategic positions in the Pacific and launched a devastating bombing campaign against Japanese cities, making it indisputably clear to the Japanese leadership that military victory against the United States was outright impossible. Despite this harsh reality, Tokyo proved unwilling to admit defeat and accept the terms of the Potsdam Declaration, but instead fortified the southern beaches of Kyushu, Japan’s southernmost main island, where the Japanese military – correctly – anticipated that the first part of the American invasion was planned to take place. Tokyo’s strategic prognosis lagged far behind its tactical predictions, however, as the Japanese General Staff believed in July 1945 that “it is unlikely that the Soviet Union will initiate military action against Japan this year” (Senshishitsu 1974, 328). Confident in the security of its northern flank, the Japanese General Staff intended to inflict such heavy casualties on America’s forces during their invasion of Kyushu that Japan could reach a negotiated peace with a war-weary United States before a Soviet entry into the Pacific War.

The US government was well aware that the Japanese leadership had realised it was fighting a losing battle. Intercepted communications between Tokyo and Moscow informed Washington that the Japanese leadership had made “tentative proposals to the Soviet government, hoping to use the Russians as mediators in a negotiated peace” (Stimson 1947, 101). To the United States, however, a conditional surrender would be unacceptable. The memory of a defeated, yet speedily recovering Germany that, only 21 years after being defeated in WWI, was capable of unleashing WWII and swiftly conquering most of continental Europe was still fresh on President Truman’s mind, “and he was determined not to accept terms with Japan that would provide what he referred to in one of his speeches as a ‘temporary respite’” (Maddox 2001, 60).

Henry L. Stimson, US Secretary of War during WWII, seconded President Truman, stating that, “the principal political, social, and military objective of the United States in the summer of 1945 was the prompt and complete surrender of Japan” (Stimson 1947, 101). The destruction of two Japanese cities with nuclear bombs was deemed as the fasted way to achieve this objective and to thereby bring an end to WWII; while it was clear by mid-1945 that Japan’s defeat was merely a matter of time, the US leadership began to fear that the American populace might grow overly war-weary if the fighting wasn’t ended soon, as every additional day of fighting cost more American lives. Under such public pressure, the US government might have found itself compelled to grant Japan a conditional surrender, something the it was not willing to accept (Pearlman 1996, 25).

The US military and political leadership was particularly concerned about the projected casualties of Operation Downfall, the planned invasion of the Japanese home islands, starting at the southern island of Kyushu. In a radio address to the nation, President Truman therefore justified the deployment of nuclear weapons “to shorten the agony of war, in order to save the lives of thousands and thousands of young Americans” (Walker 2001, 69). Not everyone in Washington bought into this argument, though, and many “high U.S. officials were [not] convinced in the summer of 1945 that victory would be accomplished without a landing on Kyushu” (ibid, 67). However, even this assessment was likely incorrect, as subsequent “information and testimonies that appeared after the war suggested that neither the bomb nor the invasion was essential to force a Japanese surrender” (ibid).

Even without access to such information at the time, a better assessment of Japan’s strategic situation would have been possible, as, unbeknown to Japan, Stalin had reassured the Allies during both the Tehran and Yalta Conferences that the Soviet entry into the Pacific War would follow three months after Germany’s surrender. The United States was therefore well aware of the impending Soviet entry into the Pacific War. However, as Bernstein (1995, 148-9) notes,

Most American leaders did not believe that the Soviet entry into the war against Japan would make a decisive difference and greatly speed Japan’s surrender. Generally, they believed that the U.S.S.R.’s entry would help end the war — ideally, before the massive invasion of Kyushu.

Considering the untenable military and diplomatic situation that Japan would be in after a Soviet entry into the Pacific War, it is surprising that US leaders failed to see that Japanese hopes for a conditional surrender would be completely shattered. A better understanding of Japan’s strategic reasoning could have made it clear that with the impending Soviet entry into the war, the Supreme War Council would had no options left but to surrender unconditionally – or decide to fight until the bitter end, in which case the destruction of entire cities with nuclear weapons would not have brought about any change to the Supreme War Council’s suicidal mindset.

While the traditionalist interpretation argues that the devastation caused by the nuclear bombs forced Tokyo to surrender before an American invasion, revisionists raise the point that there is little evidence that the Supreme War Council was sufficiently shocked by the nuclear bombs’ destructive effects. They underline this point by emphasising the marginal attention the Japanese government paid to the devastating conventional air raids and fire bombings of Japanese cities in the 14 months prior to the nuclear attacks: After small scale bombings in 1942 and the following year yielded only marginal results, the United States’ Army Air Force began its strategic bombing campaign against Japanese cities and military installations in earnest in June 1944. Particularly the deployment of firebombs proved highly effective against Japan’s predominantly wooden residential structures, causing significant damage to its infrastructure and high casualty rates amongst its population. Historian Mark Selden (2009) attributes the devastating intensity of the strategic bombing campaign against Japan’s cities to an amalgamation of “technological breakthroughs, American nationalism, and the erosion of moral and political scruples about killing of civilians, perhaps intensified by the racism that crystallized in the Pacific theater” (87). Importantly, Wilson (2013) reminds that “the first of the conventional raids, a night attack on Tokyo on March 9-10, 1945, remains the single most destructive attack on a city in the history of war. Something like 16 square miles of the city were burned out” – more than in Hiroshima and Nagasaki combined. He continues that “an estimated 120,000 Japanese lost their lives — the single highest death toll of any bombing attack on a city.”

The overall effects of the strategic bombing campaign against Japan offers another strand of the revisionist argument that the strategic bombing, nuclear and conventional, of Japanese cities had much less influence on Tokyo’s decision to surrender prior to a US invasion than traditionalists assume. According to Wilson (2013),

In the summer of 1945, the U.S. Army Air Force carried out one of the most intense campaigns of city destruction in the history of the world. Sixty-eight cities in Japan were attacked and all of them were either partially or completely destroyed. An estimated 1.7 million people were made homeless, 300,000 were killed, and 750,000 were wounded. Sixty-six of these raids were carried out with conventional bombs, two with atomic bombs.

While many Japanese cities were devastated, its army was still largely intact and well stocked. Japan’s economy had already suffered a severe blow following the American sea blockade, which effectively reduced the impact of strategic bombing. Moreover, there were little signs of a diminishing resolve among Japanese civilians, who were, as post-war surveys show, willing to continue the war (Houston 1995, 178). Moreover, according to the United States Strategic Bombing Survey (1946), “ninety-seven percent of Japan’s stocks of guns, shells, explosives, and other military supplies were thoroughly protected in dispersed or underground storage depots, and were not vulnerable to air attack.” The impact of the nuclear bombings on Japan’s fighting force and its defences in Kyushu, which was the primary consideration of the militarist government, was therefore negligible.

Critics of the traditionalist account therefore argue that not the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but instead the Soviet Union’s entry into the war against Japan constituted the final stroke to Japan’s hopes for conditional surrender, rendering any further fighting futile. Since Japan’s government had “signed a five-year neutrality pact with the Soviets in April of 1941, which would expire in 1946,” (Wilson 2013) some of its civilian members were hoping for the option of negotiated peace after a conditional surrender, brokered by the neutral Soviet Union – which had her own interest of keeping the United States out of East Asia as much as possible. However, with the Soviet declaration of war and invasion of Manchuria, this hope was immediately off the table. Instead, Japan now faced the risk of a Soviet invasion in the unprotected northern part of its home islands. Suddenly surrounded by enemies, the General Staff was forced to accept that the prospects of a “glorious” last stand against an American invasion – with the hopes of inflicting heavy casualties and reaching a negotiated peace with the United States – were utterly shattered. In order to avoid a Soviet occupation and to end the now completely pointless suffering and death of Japanese soldiers and civilians, unconditional surrender was the only viable course of action.

Eighty years on, the available information suggest that the US leadership overestimated the strategic impact of the nuclear bombings on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. A more proficient reflection of Japan’s strategic situation could have led the US government to the conclusion that the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was unnecessary. Being aware of the imminent Soviet entry into the Pacific War, President Truman could have postponed the deployment of nuclear weapons by only a few days to wait for the effects of the Soviet declaration of war. Had Tokyo shown no reaction to this, the United States could have still deployed its nuclear bombs to try and force a Japanese surrender.

Bibliography

Alperovitz, Gal. Atomic Diplomacy: Hiroshima and Potsdam. The Use of the Atomic Bomb and the American Confrontation with Soviet Power, 2nd ed. London: Pluto Press, 1994.

Bernstein, Barton J. The Atomic Bombings Reconsidered. Foreign Affairs, 74:1 (Jan./Feb. 1995).

Edmonton Journal. “Atomic Bomb Seen as Cheap at Price.” 7 August 1945.

Hasegawa, Tsuyoshi. “The Atomic Bombs and the Soviet Invasion: What Drove Japan’s Decision to Surrender?” In The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol 5, Iss 8 (1 August 2007).

Hewlett, Richard G., Oscar E. Anderson. The New World, 1939–1946. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1962.

Houston, John W. “The Impact of Strategic Bombing in the Pacific.” In Journal of American-East Asian Relations, Iss 4 (Summer 1995), 169-79.

Maddox, Robert James. “A Necessary and Justified Decision.” In Maddock, Jane J. (ed.): The Nuclear Age. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2001.

Pearlman, Michael D. Unconditional Surrender, Demobilization, and the Atomic Bomb. Combat Studies Insulate, 1996.

Selden, Mark. “A Forgotten Holocaust: U.S. Bombing Strategy, the Destruction of Japanese Cities, and the American Way of War from the Pacific War to Iraq.” In: Yuki Tanaka, Marilyn B. Young (eds.), Bombing Civilians: A Twentieth Century History. New York City, NY: The New Press, 2009.

Senshishitsu, Boeicho Boeikenshujo. Kantogun,Vol. 2, Kantokuen, Shusenji no taiso sen. Tokyo: Asagumo shinbunsha, 1974.

Stimson, Henry L. “The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb.” Harper’s Magazine, 194:1161 (Feb. 1947).

United States Strategic Bombing Survey – Summary Report (Pacific War). Washington, D.C., 1 July 1946. Available at http://www.anesi.com/ussbs01.htm.

Walker, J. Samuel. “A Hasty Decision with Multiple Motivations.” In Maddock, Jane J. (ed.): The Nuclear Age. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2001.

Weingartner, James J. “Trophies of War: U.S. Troops and the Mutilation of Japanese War Dead, 1941–1945.” In Pacific Historical Review, Iss 61, No 1 (February 1992): 53-67. doi:10.2307/3640788

Wilson, Ward. “The Bomb Didn’t Beat Japan… Stalin Did. Have 70 years of nuclear policy been based on a lie?” Foreign Policy, 30 May 2013. Available at https://foreignpolicy.com/2013/05/30/the-bomb-didnt-beat-japan-stalin-did/.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- (Re)Imagining Japan: Hiroshima, Nagasaki and Victimhood Nationalism

- From Hiroshima to Ukraine: Nuclear Taboo and Strategic Morality Under Pressure

- Opinion – Reassessing Military Misconceptions in the American-Japanese Alliance

- Opinion – The Potential of Strategic Ambiguity for South Korean Security

- Opinion – Japan’s 3/11: Ten Years On

- Opinion – The US Doesn’t Need More Nuclear Weapons