It was a nightmare for Americans. First there were the contested Florida election results that required Supreme Court intervention to resolve, then the horrible terrorist attacks on New York City and Washington DC that took so many innocent lives, then the two retaliatory wars where quick battlefield successes turned into brutally costly, dragged out contests with bands of criminal, ethnic, and religious fanatics, then the awful storm destruction along the Gulf Coast and the flooding of New Orleans that placed governmental ineptitude on global display, and finally, an financial bubble that when it burst destroyed millions of jobs and many more dreams. The George W. Bush years are not remembered fondly.

It was a nightmare for Americans. First there were the contested Florida election results that required Supreme Court intervention to resolve, then the horrible terrorist attacks on New York City and Washington DC that took so many innocent lives, then the two retaliatory wars where quick battlefield successes turned into brutally costly, dragged out contests with bands of criminal, ethnic, and religious fanatics, then the awful storm destruction along the Gulf Coast and the flooding of New Orleans that placed governmental ineptitude on global display, and finally, an financial bubble that when it burst destroyed millions of jobs and many more dreams. The George W. Bush years are not remembered fondly.

Throughout it all there was the ersatz cowboy backslapping informality, the mangled sentences, and the misplaced loyalty to hopelessly bad appointees that grated. He often displayed a deer caught in the headlights quality in his big public moments that did not help generate confidence in his leadership. He was in the end as he said “The Decider,” but in being that he never conveyed the notion that deciding involved much deep thinking or carried with it any lingering doubts. Instead, there was just a pouty combativeness when things did not turn out well as too frequently was the case.

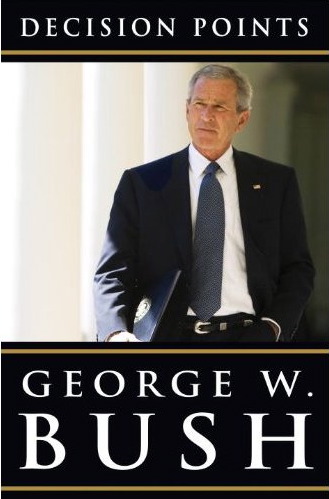

Decision Points is George W. Bush’s well received memoir. The favorable reception needs some explaining. It is not that the book is very revealing or insightful about his time as president. There are some big gaps in its degree of frankness as I will discuss later. It is also not that Bush has many friends left from that time. Conservatives now remember him as a big spending, big deficit president who tried to buy acceptance with public dollars from those who thought him a heartless rich kid. Liberals are still bitter over the lost 2000 election and the two Bush initiated wars. And moderates hold against him the deep recession and the divisive political environment. He promised before coming into office to be a “uniter,” but no one, except perhaps for his successor, was a better divider than was Bush the Second.

More likely the book’s appeal lies in the warm sections about family and the lack of rancor in which Bush offers a defense of his administration. In contrast with many political autobiographies, including Tony Blair’s, Bush doesn’t attempt to belittle his rivals or demean his opponents. He admits many errors and avoids blaming others for the big failures. He doesn’t trash his Secretary of Defense or his generals for things going badly in Iraq and Afghanistan even though they also made important mistakes, nor does he attempt to pass on a major share of the responsibility for the Katrina catastrophe to state and local officials although well he could given the way they behaved. He notes problems he had with other people, but only in the mildest way and usually adding some complement as well. Mostly, he provides a straight forward and familiar defense of why he ordered water boarding of captured terrorist leaders, deposed Saddam Hussein, or bailed out the biggest financial institutions. He is sure that history will be his vindication. He is, as he likes to say often, at peace with himself for what happened during his presidency, and thus not looking for excuses or fault.

Unfortunately, Bush offers no real insight into the crucial war decisions. Take the decision to invade Iraq. Yes, there are the standard explanations: Saddam was an evil man who harbored some terrorists and was ruthless with his own people; we all thought there were WMD in Iraq; and wouldn’t it be better if the Middle East had democratic governments. It is also obvious that the world knows many evil men, that the WMD was the issue that some Democrats and Tony Blair demanded as cover, and that the test of the Democratic Peace theory in the Middle East is far off and potentially frightful. The decision to go after Saddam seems to have been closely held and taken just after 9/11. President Bush, Vice President Cheney and perhaps no one else made the commitment to include regime change in Iraq in the Global War On Terror, and it is not clear why. Missing are discussions about the likely impact on or involvement of Saudi Arabia and Iran in the decision. Many of the costs of removing Saddam were indeed anticipated by senior US officials and military planners as well as by allied governments, dissenting or not, but we are not told much at all about the gains that were anticipated by President Bush that would justify paying those costs. There has to be more to the story than what Bush provides in the book.

With the refusal of the Taliban to hand over Bin Laden, the Afghan invasion was inevitable. Bush could not continue the Clinton’s policy of retaliatory cruise missile strikes. Bin Laden had to be hunted and the Taliban driven from government. The American people would have tolerated nothing less. Given this context, the actions Bush took in invading Afghanistan seemed reasonable as he tried to limit the size of the American force used and the project’s goals, not wishing for Americans to be viewed as occupiers by the Afghans as were the Soviets. The task of rebuilding Afghanistan was largely left to international organizations including the UN and NATO. But then the rhetoric began to exceed the design. Bush said often, and repeats in the book, that the US would never abandon Afghanistan and Pakistan again as it supposed did after the Soviets were driven out, but he also decided that the Afghan forces that the US were training were to be kept modest in scale so as, he asserts, not to burden the Afghan government with unsustainable expenses. What was it? Were they to be on their own or weren’t they? Soon the Taliban began drifting back into Afghanistan from their Pakistan retreat and the violence escalated. Bush doesn’t try to explain the contradiction or suggest how the US can ever extricate itself from Afghanistan.

Image by Beverly and Pack

Hauntingly, it seems that the Bush years will never go away. Combined, the wars have already cost a trillion dollars and both meters continue to run. Bush created new entitlements at home and abroad, and then cut the taxes needed to support them. On his watch the economy went into a lingering, deep recession and the government’s budget shifted from substantial surpluses to deficits that soar beyond likely redemption. A familiar George W. Bush phrase which hardly appears in the book is “Stay the Course.” This should have been the title of his memoir instead of Decision Points. For good or bad, America is still on the course George W. Bush set.

Harvey M. Sapolsky is Professor of Public Policy and Organization, Emeritus at MIT and was until recently the Director of the MIT Security Studies Program. He has been a visiting professor at the University of Michigan and the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. In the defense field he has served as a consultant or panel member for a number of government commissions and study groups. His most recent books are US DEFENSE POLITICS written with Eugene Gholz and Caitlin Talmadge and US MILITARY INNOVATION SINCE THE COLD WAR edited with Benjamin Friedman and Brendan Green, both published by Routledge.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- George H.W. Bush and International Relations: A World in Motion After the Berlin Wall

- The PNAC (1997–2006) and the Post-Cold War ‘Neoconservative Moment’

- Analysing the Bush Doctrine Through Carl Schmitt’s Concept of the Political

- Opinion – International Humanitarian Law Should Have Been Part of the Taliban Deal

- The Afghan Peace Agreement and Its Problems

- Peace in Afghanistan?