This interview is part of our Black History Month features. The interviews speak to the fundamental aims of Black History Month and discuss current research and projects, as well as advice for young scholars.

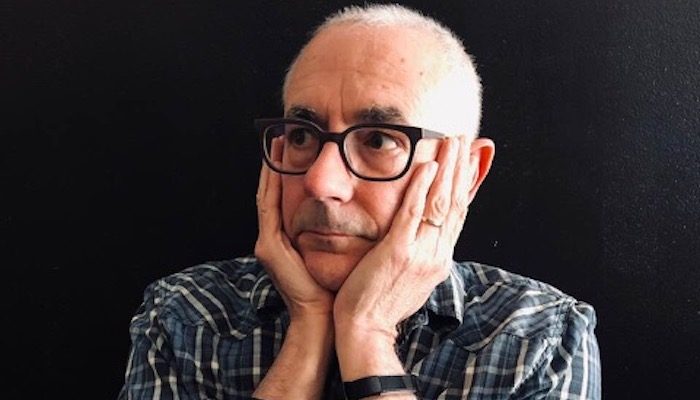

Robert Vitalis has a PhD in Political Science from MIT and is currently full Professor of Political Science at the University of Pennsylvania. He began his career as a specialist in the political economy of the Middle East, but in the late 1990s he began to explore records that appeared to upend the history that international relations scholars told about the origins of the field. His growing interest in racism as a force in world politics and in the works of W. E. B Du Bois influenced the writing of his account of the Jim Crow organization of life under the western oil companies in the Persian Gulf (see America’s Kingdom: Mythmaking on the Saudi Oil Frontier, 2005) and culminated in his revisionist history of the IR discipline and its black internationalist counter-tradition, White World Order, Black Power Politics: the birth of American International Relations (2015). His latest book, Oilcraft: The Haunting of U.S. Primacy in the Gulf, will be published later this spring.

Where do you see the most exciting research/debates happening in your field?

This is probably not what young and ambitious theorists want to hear but I hardly identify with a field at this point in my career, and no longer organize my undergraduate teaching as if disciplines matter. The critical area studies and political economy traditions with which I identified are dead. Political science has turned its back on what area studies after Edward Said’s Orientalism understood as essential to challenging power. See Zach Lockman’s Contending Visions of the Middle East for details.

International Relations is in a worst state since critical voices and perspectives have faced even more formidable opposition. Consider the new mission statement by the current leadership of the Centre for Advanced International Theory at Sussex, which identifies the essential need for research “free of the requirement for direct policy relevance and reflexive of the knowledge/power nexus.” And now think how impossibly wide the gulf is between what they call for and what every leading political science and international relations department in the United States considers to be the prime directive of their research, teaching, and institution building since 9/11. I have tried attending job talks and seminars, since my department chases the same six “star” candidates that its competitors do in each field each year, but no longer do so.

Basically, I’ve stopped reading journals and teaching articles as well. I teach books exclusively, and get great pleasure and inspiration from reading across disciplines. Quinn Slobodian’s The Globalists: The End of Empire and the Birth of Neoliberalism, Kathleen Belew’s Bring the War Home: The White Power Movement and Paramilitary America, and Amy Offner’s Sorting Out the Mixed Economy are next on my list. I’m looking forward to reading Dan Nexon’s new book, which he has co-written with Alexander Cooley, Exit from Hegemony. I love Patricia Owen’s new project on women in international thought. I’ve done what I can to make sure the work of folks like Isaac Kemola (Making the World Global), Neha Vora (Teach for Arabia) and Pascal Menoret (Graveyard of Clerics) make it into print. And I’ve made it a point to support the hiring and promotion of those in the United States who come closest to the Sussex ideal in their combining theory and international relations (e.g. Jairus Victor Grove, Alex Barder, Dan Levine) even though the approach in my own work is far different from their own.

How has the way you understand the world changed over time, and what (or who) prompted the most significant shifts in your thinking?

The question makes it easy to invent or romanticize my past, which I will try to avoid. I suppose I have been wrestling with my original ready embrace of two different although at times intersecting fields – maybe genres is better – in the study of U.S. imperialism and where and how they lead us astray. The first is the revisionist tradition in what used to be called diplomatic history associated with William Appleman Williams and the Wisconsin school. I was still an undergraduate, back from a year study abroad in Egypt and Israel (not a common thing in 1976), and took a seminar in diplomatic history with Carolyn “Rusti” Eisenberg, then a young scholar working on Cold War foreign policy. I have been wrestling with the adequacy or not of their and the more brutalist neo-Marxian variants of societal or innenpolitik or instrumentalist or structuralist answers to what drives U.S. foreign policy since. The second is what we used to call historical comparative political economy or dependency and post-dependency approaches to roughly the same issue as seen from and experienced by places like Egypt and Saudi Arabia. I suppose there is a third literature or genre, namely Said’s critique of Orientalism and its afterlives, although it played a less important role than the others in what I do.

In my book America’s Kingdom, I depicted the same intellectual trajectory as follows: “When I started this project I described myself as a political economist, and I thought of political economy as a kind of excavation project of material lying beneath the surface of ideology and culture. Now at the end of a decade-long endeavor, I tend to use a different metaphor, and think of my work more in terms of reverse-engineering of particular processes of mythmaking.” I called White World Order a sequel to America’s Kingdom and its account of the unbroken past of hierarchy on the world mining frontiers. I said that professional international relations did something similar to what the oil companies’ agents did in rewriting history, even if “some may still believe the oil sector orders of magnitude more important to the twentieth century than the knowledge industry.”

In my newest book, Oilcraft—we are still going around with the marketers about the subtitle, but roughly How Scarcity and Security Haunt U.S. Energy Policy – due out next summer, I return to the “raw materialism” that has misled the left now for decades. Thirty years ago, Fred Halliday skewered the “vulgar Marxist explanations of American foreign policy” that reduce complex determinations to the quest for “raw materials and markets.” It has only gotten worse since as I show activist intellectuals as actively engaged in mythmaking as clients of the Saudis are.

What is the importance of Black History Month and what does it represent to you?

It invites us to set the record straight. It has mattered to the way my daughter, who is in third grade, is learning US history in comparison to how I did in the early 1960s. Yet two often repeated criticisms make sense to me. One is that the changes are less than ought to be the case and the effect of having a black history month is paradoxically to prevent more sweeping and comprehensive changes in how we view the past. The other is the inevitable romanticization of figures such as Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, and others in the rewritten textbooks and on the History Channel, and so forth. What my work represents is an effort to take seriously the challenge that black studies presents us all, in fields that folks have long argued are far removed from the issues raised by it.

Recently you engaged in a historiographic debate on the development of the discipline of International Relations in the United States. What are the most common myths surrounding the origin of the discipline and how has its teaching contributed to erasure of its racial and imperialist character?

Was there a debate? No one has challenged the book so far on any point raised in it. As I said in White World Order the findings are or ought to be considered banal. We have a discipline that historically takes as its raison d’etre resolving the security dilemmas of the state (and critics might think legitimating its exercise of power), emerging at a time when the great however irrational fear was as Lothrop Stoddard put it and was celebrated for doing so, “The Rising Tide of Color Against White World Supremacy.” My book “discovers” exactly what we would expect, all else equal. What troubles various leading figures in the discipline and such intellectual middlemen as Gideon Rose in Foreign Affairs is my suggesting that the ideas that undergird hierarchy, including belief in the superiority of some, the inferiority of others, ones that animated the disciplines’ forgotten leaders, have a long half-life. A venerable tradition in Americans self-understanding, both in popular culture and in the high scholarly arts is to presume we have turned the corner on the past of racism, segregation, and the like. It is my suggesting otherwise that has generated the only not serious and rather emotional criticism of the book to date. Rose told his readers that I have made an important contribution to rethinking the past but I clearly believe that the U.S. today is “evil.” Ironically, it is precisely the same claim that true believers made about my alleged motives or unstated views in my last book America’s Kingdom.

In the preface of your book you explain how you discovered that Foreign Affairs was originally called the Journal of Race Development, whose editorial board was composed by controversial scholars such as Ellsworth Huntington, who openly embraced environmental determinism. How influential was biological and geographic determinism in the making of American International Relations?

First, there was nothing controversial about Ellsworth Huntington at the time. Rather he was considered required reading and his ideas about environmental determinism were taken as gospel. The only controversial scholar on the first editorial board was W. E. B. Du Bois, both because some saw his 1903 essay collection Souls of Black Folk as beyond the pale save until his later book Darkwater, which was even more controversial. And as I note in the book, another reason why Du Bois was controversial was because Harvard actually trained him. That said, I think we haven’t actually ever assessed the continued influence of biological/geographic/environmental determinism on the field from then till now. Kaplan was busy resurrecting selected parts of Mackinder who is still treated as some kind of great father of geopolitics; there was “lateral pressure” theory for a while treated as essential to the discipline when I was a graduate student. Many other examples might be cited. In addition, as I note in the book, no one has traced the significance of U.S. political scientists writing in Mankind Quarterly, a journal of scientific racism founded in 1961 and still around today.

Could you explain the Howard School and its main proponents? How does their work contribute to the understanding of racism in world politics?

Acknowledging the conceit (“school”), Howard University in Washington DC was a kind of flagship or most prestigious of the country’s historically black colleges and universities, and what I show in the book is that a set of scholars not usually recognized as having any role to play in the discipline of international relations understood themselves as seriously concerned with theory and dedicated to upending key parts of the then dominant paradigm. That dominant paradigm was that imperialism was a blessing bestowed on inferior folks or a necessity due to that inferiority. They—Alain Locke, Ralph Bunche, E Franklin Frazier, Eric Williiams, and Merze Tate—whatever their differences in approach, Marxist commitments, and so forth, savaged these ideas. Reading them would require us minimally to rewrite the history of the critique of imperialism to recognize that they got there first, before the William Appleman Williams and Immanuel Wallersteins of the world. They influenced African and Caribbean intellectuals for sure, but the white academy didn’t read them because they wouldn’t hire them or publish them in their journals. Consider my claim that Ralph Bunche is probably the only president of the American Political Science Association who was never published in the discipline’s journal. Political science embraced him as a symbol of its own enlightened attitude toward diversity without knowing a thing about his scholarship.

How important is it to deconstruct and retell the disciplinary history of International Relations?

Here is why I think it is. You or your readers may disagree. It exposes the pretense of originality and the seemingly upward curve of knowledge at the hands of those that the TRIPS survey and other star-making machinery rank as the top five or ten or twenty greatest minds of the field. It helps deflate the dream that IR is or is becoming a “science” and not, as it always has been and will be, an “art.” I don’t blame younger scholars for believing otherwise or acting “as if” it were the case. To do so would be to sabotage one’s own career. It is still fiction.

A second consequence, as I hope my book makes plain, is to reveal just how parochial or perhaps provincial is the better term IR is in the United States. It is no less culturally constituted and blinded than that world that we like to imagine beyond the “ivory tower.” I should say that I now realize that it is these consequences and not simply that I was bringing forgotten or unknown black scholars into the tradition that led leading lights to work overtime to keep my project from getting funded.

What is the most important advice you would give to young scholars of International Relations?

I was reluctant to answer this question because I have grown so cynical about the profession, which indeed now operates like other parts of the cultural economy of stars, high salaries, exploitation, and the like. But there is one thing I would urge them to consider, as I make clear in my book. What we do matters and has consequence primarily in the classroom, the department, the university, and the professional association, and we ought to strive for a fairer, less sexist, less racist academy. The dream of mattering to the state or to social movements is mostly if not completely a fantasy.