The reflection on this question isn’t new. Since the 1980s, the Subaltern Studies group studies and publishes about postcolonial societies and, since the 1990s, Cynthia Enloe questions “Where are women in International Relations”? This concern isn’t disconnected to the new dynamics of the post-Cold War context and the insertion of new themes (feminism and human rights, for example) in the international agenda – previously considered as part of the domestic sphere. In this way, since then, there is a wide scientific production about the theme. The intention in this paper is to rescue what has been produced recently departing from Latin America, seeking, as well, to offer an answer that befits especially the decolonial feminism thinking.

The Global South Theory comes up in the 2000s, updating the World Systems Theory, which, between 1945–1989, offered the perspective of classifying countries from the economic development point of view. From a critical position, the theorists of the Global South perspective seek to present the “South” as a geopolitics space composed of countries located in the periphery of the World System, as well as, political, economically, and intellectually dependents on countries that compose the “North”. Besides, this still indicates that inequalities do not occur only between States, but also in the interior of groups of countries that adopt different forms of international insertion (Muñoz; Coelho; Villamar, 2019).

In that way, they highlight the fact that traditional International Relations theories (neoliberalism and neorealism) weren’t able to consider the different matters that affect the South countries, being, a lot of them, the results of the center-periphery relations. These theories also failed in understanding and realizing the “South” as a space of existence and resistance, and not only as a space of vulnerabilities, as sometimes is pointed by the hegemonic theories. In that way, it is worth to highlight the words of Echart and Villarreal:

‘The South perspective is, therefore, also a way to make visible the invisible world of resistance, resilience, and creativity everyday practices from indigenous, women, migrants, young people, among others’ (Echart e Villareal, 2018, 2019) (own translation).

In this way of production of critical knowledge and complementing the theory of Global South, Feminism emerges in the International Relations area in the 1980s, related to other theories that already existed at the time (such as Liberal, Radical and Marxist theories, among others). However, it is not just about a simple addition, considering that feminist theorists brought considerable changes to the theoretical paradigms set from the rejection to the traditional method of knowledge, fighting power with the mainstream, by claiming there aren’t neutral lenses to see the reality and that the global perception of the traditional theories banishes women from the political field.

Once it is understood that both Global South Feminism perspectives dispute theoretical and praxis power with the mainstream, it’s necessary to demonstrate this space of knowledge that intends to reflect on what the International Relations have to learn concerning the feminist policies in Global South. In this way, Latin America’s gender policies depart from experience, from the “local” and then get a long reach, unlike the North-hegemonic policies that intend to be universal.

Enloe (2013) highlights the fact that International Relations scholars have historically dedicated themselves to Security studies, thinking about wars and revolutions emphasizing male protagonism and making invisible the women’s role in these events, whether by actively participating in the conflicts between states and/or by caring activities in the conflicts’ backstage. This women’s invisibility, as the author stated, is part of a male privilege set in a global misogynistic society, in which the people who create the narratives (authors, people who appear in the media, among others) are, mostly, men. As a consequence, what women have to say about different topics, especially in the public and international spheres, does not have the same value as the men’s narrative. Therefore, the author defended the need of having a feminist vision about International Relations matters, because, only this way, the scholars of the area will understand the events completely. Besides this, the author also highlighted the matter of watching the daily lives of women and children to understand the practical policies (ENLOE, 2013). So, from this point, we will think about Latin American women.

In pre-Colombian societies, Federici (2017) explained that women were in an equal economic position. From the arrival of Europeans, the colonizers transformed the indigenous women in slaves, forcing them to work hard in mines and to prepare meals. Besides this, Federici (2017) highlighted that no woman was safe from rape. In this context, called by Federici (2017) as “witch-hunting”, indigenous women fought against the colonizers’ practices and were the mainly responsible for the survival of the native American bond with the land, local religions and with nature, being a source of anti-colonial and anti-capitalist resistance for more than five hundred years.

In a complementary way, María Lugones (2019) is an important decolonial feminist who dedicates herself to theorize the different forms of resistance to oppression. In her paper “Rumo a um feminismo decolonial”, she proposed a colonial capitalist modernity reinterpretation, understanding that the colonial imposition of genders goes through ecological, economical and government issues, different forms of knowledge, religiosity and daily practices that teach communities how to preserve the world or how to ruin it (LUGONES, 2019).

The idea of modernity, in the author’s perspective, thinking of the relationship of the European people and those colonized from Latin America and the Caribbean, organized the world ontologically in atomic, homogeneous and separable categories, in a way that only white European men and owners were considered as “humans”, which brings the black and third world feminism criticism about the intersection of race, social class, and sexuality exceeding the modernity categories. To the author, it’s still necessary to consider in the analysis of colonizer vs. colonized interaction, the role of Cristianity’s dissemination and the presence of an ideological conception that the “man” was the human being by excellence, meanwhile females were noticed by the normative understanding “woman” as the inversion of men. Quoting the author:

The colonial civilizing process was the euphemistic mask of the brutal access to people’s bodies by the unthinkable exploration, violent sexual violation, reproduction control […] the Christian confession, the sin and the Manichean division between good and evil marked the female sexuality as evil – colonized females were related to the devil (LUGONES, 2019, p.360) (own translation).

Lugones (2019, p.360) mentioned that this project of civilizing process contributed to the colonization of the memory and of the people’s understanding about themselves, about reality, and their relationship with the world. Despite this scenario, colonized indigenous women did not give up easily to the violations that were committed, and, as a community, they acted in resistance to Europeans. About this matter, the author commented:

No one resists to the coloniality of genders alone. It’s only possible to resist it by understanding the world and life experience that is shared and able to understand its own actions – assuring the right recognition. The communities, and not the individuals, make it possible to do; people produce with each other, never isolated. The oral history, the passing from hand to hand of the experienced practices, values, beliefs, ontologies, spacetime, and cosmologies compose people. The daily life production, in which we exist, produces who we are, as it provides us clothes, food, economies and ecologies, gestures, rhythms, habitats, and space and time notions; all of them are significant products to us. But it is important to highlight that these paths are not only different: they confirm an ideal of life that is beyond profits, a community beyond individualism, a “being” instead of a development; beings in relation instead of being separated dichotomously over and over again in hierarchically and violently ordered fragments. These ways of being, of giving value and believing established themselves as part of the resistant answer to coloniality (LUGONES, 2019, p.372-3) (own translation).

In this way, recovering Latin America history, we realize that looking at the events from a Global South perspective is to show that this geopolitical space isn’t just about vulnerabilities, but also about the power of agency that these countries have to solve their own problems.

It is possible to say that one of the articulation strategies of feminist movements is through networks. Echart Muñoz (2017, p.132) claimed that the process of human rights progress in the international sphere had a diversity of women, such as suffragists, soviets, proletarians and free women, leaders of independence movements in South countries, in movements for civil rights, in transnational nets present in international women’s dome, among others.

These women are part of what Ballestrin (2017, p.1051) named “feminismos subalternos”, or subaltern feminisms. In other words, the different articulation of women movements, academic or not, including post-colonial feminism, third world feminism, black feminism, indigenous feminism, community feminism, mestizo feminism, Latin-American feminism, African feminism, Islamic feminism, South feminism, decolonial feminism, feminism on the border, transcultural feminist engagement, among others, and that, in general, were represented by the Anglo-Saxon and European feminism as movements of women who were either poor, workers, poorly schooled, dominated and/or victims.

Thereby, Echart Muñoz (2017, p.137) and Ballestrin (2017, p.1051) both say that these women movements had a strong involvement in defending their rights, in the domestic sphere as well as in the international one, through transnational networks, showing, this way, their capacity to build a fair, democratic, and according to their own realities, feminist agenda.

In the case of Global South feminism, between the 1970s and 1980s, groups of women from the region did not feel benefited joining other women from “Third World” countries around the perspective of “Women in Development” (MED) aiming to point out the inequalities in the labor market – related to the reproductive world – and to point the lower flow of women in the International Political Economy (except in the cases of women trafficking and caring tasks). The “MED” perspective criticized the liberal vision of the North about a woman’s role – it didn’t see her as an economic agent -, and formed a political agenda that dedicated itself to give visibility to projects that formalized woman in the labor market, in a way to stimulate an economic resistance. However, the demand for the insertion of women in the labor market as well as in the International Political Economy consequently generated double and triple working hours, since the caring tasks remained under their responsibility (Arrieta, 2000).

The performance of feminist movements at this time was manifested in the forms of information sharing, mutual support, and the combination of lobbying, advocacy, and direct action for the realization of their equality and empowerment goals, such as social justice and society democratization (Arrieta, 2000).

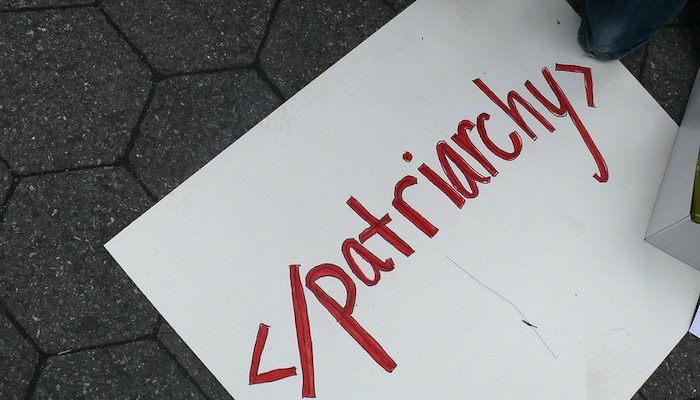

Saffioti (1987) also intersects the matter of classes indicating that feminism is not oppressed only by the social relations of domination, but by an even bigger system of oppression called patriarchy, defined as:

(…) the patriarchy is not just a system of domination, modeled by the sexist ideology. More than this, it is also an exploration system. While the domination can, for analysis effects, be situated essentially in the political and ideological fields, the exploration concerns directly the economic field’ (Saffioti, 1987) (own translation).

Therefore, when analyzing the oppression in women’s relationships, it’s important to highlight her relation with the patriarchy, in other words, with the domination system of men over women and although this dynamic is prior to the historical process of capitalism, it’s reinforced by this system both in the sphere of private relations (Perona, 2010) and in the logic of the global division of labor, as already mentioned.

It is still important to highlight that the feminist contributions from the South were essential in this renovation process of debate from the change of perception of “Women in Development” to “Gender in Development” (GED), a wider perspective that includes political rights, material development recognition and that intended to transform social, political, and economic patriarchal structures (Echart Muñoz, 2017).

The ‘GED’ proposal was articulated in the context of the formation of globalization in the 1990s, denouncing the negative effects of neoliberal policies and the minimal State to the Global South countries. Criticism also extended to the idea of a hegemonic feminism behavior as women’s spokesperson, assuming the existence of an inequality pattern between genders, but keeping in invisibility the intragender questions, such as race differences (or ethnicity) and class, that influence women in different ways concerning vulnerability. This way, they resume the debate about human rights universality as universal values, questioning the neutrality of this reality that is put to other countries by the United Nations, in the women’s conference held in Beijing in 1995 (Arrieta, 2000).

Federici (2019, p.248-51) highlighted that the Beijing Conference brought positive points as the internationalization of the feminist movement; the increase of multiple experiences Exchange and that resulted in a wider knowledge about international politics, making it possible for women who attended the Conference to establish political ties and to create networks outside the UN.

Despite these contributions, the author highlighted that the UN, a liberal institution, colonized the feminist agenda, which initially was related to criticisms of the neoliberal system and land redistribution. This way, Federici (2019, p.248-51) understands that institutions, like the UN and/or governments, by absorbing the struggles of feminist movements, weakened and disconnected them from the mass movements.

In the same sense of rescuing mass movements as resistance processes, Rivera Cusicanqui (2016) defends a revolution of episteme that runs through the creation of autonomous knowledge construction, with better articulation with community, popular, and collective practices, highlighting that knowledge is not only academic and that, when thinking about the space of Latin American knowledge construction, it is important to distance ourselves from the traditional European episteme and to think an episteme from the Latin American location.

Considering these questions, it is clear that the Global South gender policies can teach International Relations the multiplicities of legitimate knowledge, recognizing that the knowledge produced from the South does not have the goal to reverse the hierarchical logic but to complement the existing knowledge, showing the need to make visible problems that have not been overcome in these countries yet. The Global South Theory goal is also to show that this geopolitical space is not characterized only by vulnerabilities, but by the power of agency that actors in these countries have to solve their own problems, as well. The resistance, in this case, feminist resistance, still teaches how to rescue basic social movements, that go beyond borders and change the state logic disjointed from institutions, to create a history that cannot be based on the imaginary of dominant structures and that can aggregate new values for the international community.

References

ARRIETA, I., 2000. El Feminismo y los Estudios Internacionales [online]. Avaiable at: <https://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/RevEsPol/article/viewFile/46644/28128>. [Accessed 29 April 2020].

BALLESTRIN, L., 2017. Feminismos Subalternos [online]. Avaiable at: <http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0104-026X2017000301035&lng=pt&tlng=pt>. [Accessed 29 April 2020].

RIVERA CUSICANQUI, S.; DOMINGUES, J.; ESCOBAR, A; LEFF, E., 2016. Debate sobre el colonialismo intelectual y los dilemas de la teoría social latinoamericana [online]. Avaiable at: <http://www.cuestionessociologia.fahce.unlp.edu.ar/article/view/CSn14a09>. [Acessed 29 April 2020]

ECHART MUÑOZ. Movimientos de mujeres y desarrollo. En: Marta Carballo de la Riva (coord.): Género y desarrollo: cuestiones clave desde una perspectiva feminista. Madrid: IUDC/Catarata, 2017.

ECHART MUÑOZ, E.; Coelho, A. C. F; Villarreal, M.C. (Org.) . Sulatinidades: Debates do GRISUL sobre a América Latina. 1. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Périplos, 2019. v. 1, 257p .

ECHART MUÑOZ, Enara e VILLARREAL, Maria del Carmen. Women’s Struggles Against Extractivism in Latin America and the Caribbean. Contexto Internacional, p. 303-325, vol. 41(2), 2019.

ENLOE, Cynthia. Banana, beaches and bases: making feminist sense of International Politics. Berkeley University of California Press, 1990.

_______. Seriously! investigating crashes and crises as if women mattered. London: University of California Press, 2013.

FEDERICI, Silvia. Calibã e a bruxa: mulheres, corpo e acumulação primitiva. São Paulo: Editora Elefante, 2017, p.380-413.

________. O ponto zero da revolução. São Paulo: Editora Elefante, 2019, p.190-238.

LUGONES, María. Rumo a um feminismo decolonial. In: HOLLANDA, Heloisa Buarque de. Pensamento Feminista conceitos fundamentais. Rio de Janeiro: Bazar do Tempo, 2019, p.357-379.

SAFFIOTI, Heleieth. O Poder do Macho. São Paulo: Moderna, 1987.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Gender as a Post-Conflict Condition: Revisiting the Three Waves

- Opinion – Coming in from the Soviet Cold: Feminist Politics in Kazakhstan

- Notes for Thinking about Feminist Foreign Policy from a Decolonial and Communitarian Feminist Perspective

- Climate Justice in the Global South: Understanding the Environmental Legacy of Colonialism

- The Global South and UN Peace Operations

- International Relations Theory after the Cold War: China, the Global South and Non-state Actors