Why do States behave the way they do? The question has lied at the core of the theories of International Relations and Foreign Policy Analysis. Explanations range from systemic variables to State political dynamics and individual psychological factors. Perspectives have been expanding, including new disciplines and causes, transforming this area in one of the most innovative in this domain. This article departs from that intriguing question exploring decision-making processes in China and Argentina. In the first section, a brief summary of the main theories and models of foreign policy analysis will be stated, as these constitute the frame for the scholars’ research. In the second section, the main characteristics of the decision making process in China will be described. In the fourth section, the Argentine case will be explored, noting its particularities. In the fifth and concluding section, a comparative analysis of these two states will be conducted, noting similarities and differences.

Theoretical Framework: Foreign Policy Analysis

Hudson (2014) traces the development of foreign policy analysis back to 1950 with the formation of three broad groups. In the first place, group decision-making, analysing the structure and dynamics of groups at the moment of deciding a particular foreign policy. The second group of scholars is related to comparative foreign policy, which reflects the wave of scientism extended in American academy. Departing from the assumption that foreign policy behaviour can be aggregated, these theorists foster the recollection of data of different states in different moments to find determined patterns. The final group mentioned by the author underlines the idea that “the mind of a foreign policymaker is not a tabula rasa” (Hudson, 2014, p. 23). It is important to consider the beliefs, attitudes, values, conceptions, emotions and experiences, among others, of the decision makers.

Mintz and Sofrin (2017) also enumerate the key theories and models of foreign policymaking in an encyclopaedic work for Oxford University. Firstly, the rational model, where the decision-maker tends to maximize utility after analysing pros and cons of each alternative. Secondly, the cybernetic theory, stating that individuals most likely select an acceptable alternative based on their own decision procedures. Thirdly, the prospect theory sustains that decision-makers are risk-averse in terms of gains and risk-acceptant in terms of losses hence deciding from the alternative that deviates less from their reference. In the fourth term, the authors state the poliheuristic theory based on a two-stage calculus, declining ideas that are unacceptable and choosing from the remaining options. Fifthly, the aforementioned bureaucratic model with agencies maximizing their own interest in domestic politics. Related to this last one, finally, Mintz and Sofrin (2017) mention the organizational politics, where decisions are made based on standard operating procedures (SOPs).

International Relations theories have also attempted to provide explanations to general behaviours of the State. Among them, the realist paradigm with its three main branches, classical realism (Morgenthau, 1987), neorealism (Waltz, 1979) and neoclassical realism (Ripsman, Taliaferro, & Lobell, 2016) rank as the most popular. Liberal approaches have also managed to stand strong, emphasising cooperative and institutional aspects (Keohane & Nye, 1988). However, in terms of foreign policy analysis, cognitive perspective highlighting the importance of perceptions are widely used (Jervis, 1976) as well as constructivist approaches that stress identity and shared beliefs (Wendt, 2003)

In general, within these models the scholars have moved trying to explain China and Argentina’s foreign policy. Without getting involved in discussions about the explanatory power of these models, the next sections will propose, based on a review of the existing literature about the decision-making process in these countries, its main determinants.

Chinese Foreign Policy

Although the increasing importance of China has fostered the analysis about its foreign policy and its implications for the world order, this fructiferous field has more to be explored as it accounts great complexity. This section will present relevant variables about the Chinese decision-making process.

The first pertinent aspect stated by the academia is related with the importance of history and the constructed narrative surrounding it in the formulation of Chinese foreign policy. Garver (1993) underlines three aspects in this regard. Firstly, the deep studied myth of Chinese humiliation. Since the First Opium War in 1839 until the Chinese Communist Revolution, China suffered a series of humiliating acts, like indemnities, tariffs, extraterritorial jurisdiction and loss of territory. The Communist Party of China stands at the core of this “rejuvenation”, being the actor who managed to accomplish the first victory against a foreign power after the capitulation of Japan in 1945, finishing the humiliation period and giving birth to a raising pride (Wang Z. , 2008). Furthermore, this is complemented by a sentiment of cultural superiority based on the long-time extension of Chinese civilization.

The second dimension that provides insights to Chinese foreign policy is constituted by the structural constrains. Principally based on neorealist assumptions (Waltz, 1979), this perspective settles that the distribution of capacities constrain the “room for manoeuvre” (Seitz, 2007). The position a state is located in the international system, whiles no determining, helps to clarify its behaviour, no matter the internal characteristics of a state. In spite of its determination, the external dimension constitutes an essential part in the definition of Chinese foreign policy, as reflected by many scholars (Cheng & Zhang; Chen & Wang 2011). The big strategies of China, namely “leaning to one side”, “fighting with two fists”, “one united front”, “independent and peaceful”, “adopting a new profile” and “world multipolarization”, can be partially explained by structural constrains. It is possible that Chinese relative power, mainly based on its economy, military, territory, population and geographic position, reduced the effects of the international structure, allowing these changes.

The third important characteristic of Chinese foreign policy is given by the centrality of the process, based on the dynamics of its political system centred around the Communist Party of China. There is almost an agreement among chinese scholars studying this topic regarding the prominence of the paramount leader in this regard. Especially analysing the role of Mao Zedong, scholars enhance his personality and leadership characteristics as a feature that should be taken into account when explaining foreign policy strategies. This is reflected also in Deng Xiaoping’s case (Ning, 1998).

While the leadership of Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao pointed towards a more diversified and bureaucratic decision-process (Ning, 2001; Miller, 2008; Lai & Kang, 2014), the election of Xi Jinping has put the leader back at the centre. Wang (2018) highlights once again the importance of the leader in the definition of the Chinese external relations strategy when analysing the new “Major Country Diplomacy”. This particularity is also emphasized by Tao (2017), who explores “Chinese Foreign Policy With Xi Jinping Characteristics”. Consequently, it is pertinent to mention how bureaucracies deal with day-to-day decisiones (Braybrooke & Lindblom, 1963) but, at the same time, necessary to discuss if this fact generates a real impact in the high level decision-making process.

The position of some scholars about the relation between the leader and the country’s foreign policy opens the debate towards their personality. If the Chinese domestic structure is still centralized, then the different styles of commanding can explain different ways of managing the foreign affairs. An approach in this regard is provided by Zhang (2014) who builds a bridge between personality types and foreing policies..

Not withstanding the aforestsated variables, scholars tend to consider other aspects. In this sense, the role of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), the bureaucracies and the media and public opinion have been stated as relevant. However, there is evidence to support the idea that the PLA, although with a great influence especially in their expertise area, still answers to the Communist Pary leadership (Nan, 2015). Moreover, as mentioned before, while agencies are important in the definition of less relevant decisions and the implementation of the foreign policy, centrality stands as the main characteristic of Chinese decision-making process. Regarding the role of the media and public opinion, it can be considered limited mainly because of the censorship process.

In conclusion, the foreign policy decision-making process in China shows three main characteristics. Firstly, the importance of the use of history, underlined by the construced narrative of the 100 years of humiliation and, as the counterface, nationalism. The “Chinese rejuvenation” guided by the Communist Party of China gets significance under this historicla exegesis. Secondly, it is imperative to consider the structural constrains given by the distribution of power in the international system, reducing or increasing the range of options the country has. These constraints limit the possible options for China. Thirdly, it is necessary to bear in mind the prominence of the leader in the main foreing policy definitions, as particularly noticed in Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping and Xi Jinping. The State and party tend to concentrate the power in the leadership, reinforcing this aspect. This last point, finally, stresses the cruciality of approaching leaders’ personalites.

Argentinian Foreign Policy

Academia has not devoted much attention to the foreign policy decision-making process in Argentina; in some cases it is even questioned whether the country has a foreign policy (Deciancio & López Franz, 2008). In general terms, this theme can be firstly approached from a regional perspective due to the historical, geographical, political and socio-economical similarities among the countries (Holsti, 2004). Secondly, there are studies that can provide national insights for this tematic.

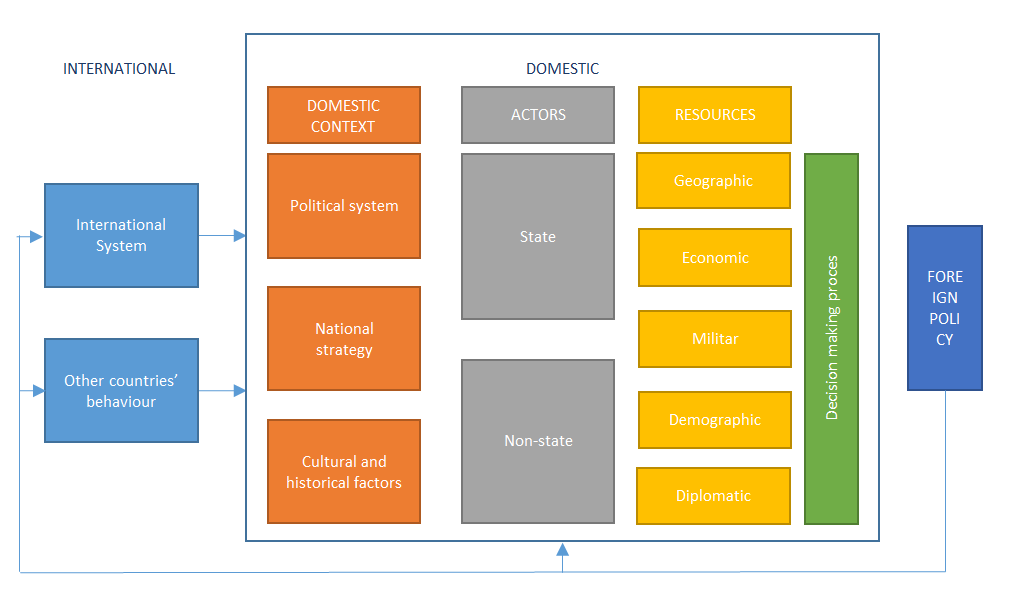

Van Klaveren (2013) proposes a division between the structure and the decision-making process to analyse this theme in Latin America. The first one is related with the external and internal conditions, while the second is associated with the actors, institutions, groups and interactions that shape a particular foreign policy action. In this sense, the author suggests the following scheme[1]:

Among the great amount of variables, some stand stronger in the Argentinian case. Regarding the international domain, the structure settles the limits for this country’s foreign policy. According to Seitz (2007), the “room of manoeuvre” is constrained in South American countries due to their limited relative power. This freedom to act internationally depends, according to this author, on three variables: structural characteristics, conjuncture or opportunity and perception of them. Of this, the first one has presented more challenges to Argentina.

On one hand, after the Spanish colonization and independence wars Argentina gained a political independence but not an economic one. Following Sunkel and Paz (1970), Argentina is characterized by an “outside developing economic model” where the emphasis is put on satisfying external demands without considering the local necessities. In this model, that stands since the colonial age but continues nowadays, Argentina internationally sells raw materials and agribusiness products and imports manufactured goods, depending completely on the international demand of its products, which implies a great limitation to its actions. For an economy to expand a limitless international demand is needed. Even more, this economic matrix is directly associated with the deteriorating terms of trade where more non-manufactured products are needed to buy the same amount of manufactured ones, restricting the possibilities of development (Krugman & Obstfeld, 2003).

Furthermore, the Spanish mercantilist economic approach to South America, extracting silver and gold, prevented the development of an accumulated capital. Without the means to build the necessary infrastructure and heavy industries, the dependence of Argentina increased significantly, leading as well to debts complications with Great Britain, United States, the International Monetary Fund and the Paris Club (Galasso, 2008). Since its foundation then the international economic structure and division of labour constrained Argentine foreign policy possibilities. The absence of proper economic power and, henceforth, dependence has direct political implications, as noted by Armstronagd (1981) and Hey (1993).

Besides the historical structural limitations, Argentina has been, on one hand, under the influence of the United States. Directly detailed in the Monroe Doctrine in 1823, this global power has exercised a tight hegemony over Latin America for almost two centuries, constraining countries’ foreign policies. In this regard, some alternatives either are “prohibited” or include high costs ranging from economic sanctions to diplomatic offensives. Therefore, is not surprising the alignment of Latin American countries with United States’ foreign policy. On the other hand, Great Britain since Argentinian independence has exercised great influence because of the complementarity of the economies and the loans provided by the insular country (Deciancio & López Franz, 2008). Once again, this reality limits Argentinian’s opportunities, in other words, in the menu of foreign policy options some are too expensive to be afforded.

In addition to international variables, are several internal dynamics must be considered when analysing Argentine foreign policy (Amorim Neto & Malamud, 2015). Russell (1990) sustains that, in a continuum between centralization and decentralization in the decision-making process, Latin American countries are located closer to the unity extreme, with a great centralization and a preponderant figure of the president. This is particularly important in Argentina, which witnesses a high centralization in its leader. (Alice, 2009; Schenoni & Ferrandi Aztiria, 2014).

According to the Constitution, the Argentine President has several functions: naming of ambassadors, ministers and business representatives with Senate agreement; signing of treaties; exercising the command of the armed forces; and declaring war with congress agreement. However, according to Barreiros and Maisley there is a grey area with functions not defined, such as that is responsible for the planning of the foreign policy strategy. The President, as being the most powerful figure within the domestic structure, might easily occupy this vague zone. Consequently, the profile of the foreign policy answers to the vision, interest and values of the current leader. In this sense, as aforementioned, it is necessary to address the president’s personality, background and formation (Soukiassian, 1994).

Furthermore, it is essential to address the participation of certain interest groups (Van Klaveren, 2013). Latin America stands as the most unequal region in terms of distribution with a high concentration in a small percentage of the population. Indeed, according to a report from the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) in 2014 the 10% of the population accounted more than 70% of the wealth of the country (Bárcena, 2016). This theme is straight related with the economic model explained above, as a concentrated economic group controls the main economic production of the country.

These corporations are, hence, an important non-state actor that seek for influence and pressures the executive power, even to the extreme of promoting military coups in order to prevent changes to the economic matrix (Valenzuela, 1978). The economic lobby groups have a considerable power as the development of the economy relies heavily on their actions. In the case of Argentina it is worth noticing the role of the Sociedad Rural, where the most important exporters of agribusiness products are nucleated. According to Miller (2000), for example, during the Uruguay Round of World Trade Organization negotiations the Sociedad Rural provided the Argentine negotiators relevant information but also conducted parallel negotiations with other actors. In addition, historically the Foreign Services has been dominated by the Argentinian economic establishment (Soukiassian, 1994).

As in the case of China, other variables can be enumerated, although they do not seem to collect the relevance the aforementioned have. Particular is the case of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which is supposed to conduct the foreign policy. Without bureaucratic force, the Minister will only stand as an important figure if there is a delegation of power from the President (Soukiassian, 1994). Not surprisingly considering the economic model and the importance of certain economic corporations, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs sometimes even lose its relevance giving the centre of the scene to the Ministry of Economy (Schenoni & Ferrandi Aztiria, 2014).

In conclusion, the decision-making process of Argentina tends to be explained by three predominant variables. In the first place, structural constrains given by the economic insertion of the country and the hegemony of United States and Great Britain in the continent. Limited are the options for Argentina in this context, where the lack of relative power does not allow major room for manoeuvre. In the second place, the role of the President as the primordial figure in the political system, falling within their responsibility the major definitions and the conduction of the foreign policy. In the third place, the role of economic corporations in the foreign policy definitions and continuation of the “outside developing economic model”, pressing the leadership towards certain directions of foreign policy and perpetuating structural dynamic.

Among China and Argentina

Notwithstanding the 20.000 kilometres that stand between Buenos Aires and Beijing, the cultural differences and the dissimilar global positioning, a comparison between the decision-making processes in these two countries can provide new perspectives about the thematic. Far from an exhaustive comparative analysis, this section intends to explore similarities and differences, wishing to open the field for future in-depth researches.

In the first place, the domestic structure implies an interesting feature. Although the Chinese political system positions closer to authoritarianism and Argentina reflects a democracy since 1983, both countries present a highly centralized structure. This domestic disposition derives in the importance of the leader, namely the General Secretary or President of the Republic, in the definition of the foreign policy. As stated above, the Chinese paramount leadership has been extensively examined, usually underlined as the main characteristic of the decision-making process (Ning, 1998; Zhang, 2014; Wang , 2018). In Argentina, although this field is still understudied, the strong presidentialism implies a special role of the leader (Russell, 1990; Soukiassian, 1994; Deciancio & López Franz, 2008; Schenoni & Ferrandi Aztiria, 2014).

This first point leads directly to another consideration mentioned in both cases. The importance of the leaders makes necessary the study of their personality, as the most important features of the foreign policy are related to its values, history and culture. While there have been attempts to analyse closely this relation in China (Zhang, 2014), Argentinian academy lacks deep revisions referring to this linkage. Comparisons between political leaders of these two countries, as slightly explored by Baschetti (2017) relating Mao Zedong with Juan Domingo Perón, can shed light upon this field.

In the second place, a similarity that also encounters differences is related with the structural constrains both countries suffered. The bipolar system limited the options both for China and Argentina, setting the framework among alternatives could be chosen. In this dimension Baschetti (2017) analysis is showing how both Mao Zedong and Juan Domingo Perón followed at some point a “third position” strategy trying to keep a neutral position facing both United States and the Soviet Union. The countries’ choice of an innovative foreign policy while dealing with a close hegemon is indissoluble of the structural variable.

However, this sphere also displays some differences. The relative capacities of each country impacts directly in the connection with the Powers of the system and the “room of manoeuvre” they have. For instance, Chinese relative power allowed China to brake with the Soviet Union while standing against the United States. Latin American countries, on the other hand, suffered direct repercussions when they decided to go against United States’ interest (Kryzanek, 1987). The distribution of power then seems to be more limiting to Argentina than to China, suffering the former one for more structural constrains.

Furthermore, as explained before, Argentinian’s economic model and international economic insertion generates a great dependence. A matrix based on exportation of agribusiness products and importation of manufactured goods implies several economic and political limitations beyond the scope of this article. However, it is worth noticing the political inferences, reducing the freedom of the country to follow national strategies. This is a radical difference with the Chinese case, which has experienced a great development in the previous years, being able to move towards an industrialized model (Erickson, 2018). The new global position of China is, in fact, largely based on its economic importance.

In the third place, a thought-provoking difference is related with the countries’ history and the political use of it. China was an established state when it witnessed the bloody encounter with the West, giving birth to what historiography postulates as “100 years of humiliation”. Argentina, although non-existent at that time, also suffered the Spanish invasion and colonization since 1492 then continued by a British economic domination. In spite of the fact that both countries transited very different destinies, it is crucial to analyse the political use of its historical evolution. While Chinese political elite has constructed a comprehensive historical narrative about its humiliation and regain of pride guided by the CPC, Argentina has failed to build up a national narrative to unite the people behind a political objective.

Lastly, a final difference that must be address concerns the role of corporations in the decision-making process. As mentioned in the third section, economic groups, especially the Sociedad Rural, play an important role in Argentinian politics. The incidence of this corporation in defining the parameters of the foreign policy to ensure the continuity of an economic model that benefits them, although barely studied, is significant. The Chinese case, on the other hand, does not present this particularity. As the most important economic activities are under control of the State the private and public interests merge. In spite of this, it is important to conduct further studies about the interactions between large Chinese private companies and the state.

In conclusion, interesting similarities and differences can be enumerated between China and Argentina. Within likenesses, in both countries the role of the leader and his/her personality is a key variable that must be addressed. Furthermore, the structure of the international system given by the distribution of power also stands as a crucial aspect, although it affects in a dissimilar way each country. As the relative power of each is not the same, China enjoys major freedom for maneuvering in the international scene. Argentina, in addition, is even more constrained by its economic dependence. As well as this, a relevant difference is given by the political use of history, vibrant in the Chinese case and absent completely in Argentina. Finally, explanations of Argentinian’s foreign policy are incomplete if the role of economic corporations is not considered, while this factor seems to be lacking in the Asian country.

As above-mentioned, foreign policy decision-making processes present great complexity. This works against the finding of a unique answer to the original question that served as departure point. This brief article attempts to contribute to this sphere by exploring comparatively the process in two different countries.

References

Acharya, A., & Buzan, B. (2010). Non-Western International Relations Theory: Perspectives On and Beyond Asia. New York: Routledge.

Alice, M. (2009). El funcionamiento del proceso de toma de decisiones y las características del negociador argentino. Buenos Aires: Consejo Argentino para las Relaciones Internacionales.

Amorim Neto, O., & Malamud, A. (2015). What Determines Foreign Policy in Latin America? Systemic versus Domestic Factors in Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico, 1946–2008. Miami: University of Miami.

Armstronagd, R. (1981). The political consequences of economic dependence. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 401-428.

Bárcena, A. (25 de January de 2016). Economic Comission for Latin American and the Caribbean . Obtained from: https://www.cepal.org/en/articulos/2016-america-latina-caribe-es-la-region-mas-desigual-mundo-como-solucionarlo

Barreiros, L., & Maisley, N.. Las relaciones exteriores en la Constitución Argentina.

Baschetti, R. (December 12th 2017). Mao y Perón. Paradigmas de una Tercera Posición. http://dangdai.com.ar/joomla/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=8501:mao-y-peron-paradigmas-de-una-tercera-posicion&catid=3:contribuciones&Itemid=11.

Braybrooke, D., & Lindblom, C. (1963). A strategy of decision. New York: The Free Press.

Brummer, K., & Hudson, V. (2015). Foreign Policy Analysis beyond North America. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Chen, D., & Wang, J. (2011). Lying Low No More: China’s New Thinking on the Tao Guang Yang Hui Strategy. China: an International Journal, 195- 216.

Cheng, J. Y.-S., & Zhang, F. W. Chinese Foreign Relation Strategies Under Mao and Deng: A Systematic and Comparative Analysis.

Coleman, K., & Quiros Varela, L. (1981). Determinants of Latin American Foreign Policies: Bureaucratic organizations and development strategies. En E. Ferris, & J. Lincoln, Latin American Foreign Policies: Global and regional dimensions. Boulder: Westview Press.

Cox, R. (1986). Social Forces, States and World Orders: Beyond International. En R. Keohane, Neorealism and its Critics (p. 204–254). New York: Columbia University Press.

Deciancio, M., & López Franz, F. (2008). Política exterior argentina e interés nacional: una mirada a Latinoamérica. San José.

Erickson, D. (2018). Why So Many Underestimate China’s True Economic Power. http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/almost-everyone-underestimates-true-economic-power-china/: University of Pennsylvania.

Ferris, E., & Lincoln, J. (1981). Latin American Foreign Policies: Global and regional dimensions. Boulder: Westview Press.

Galasso, N. (2008). De la banca Baring al FMI. Historia de la deuda externa argentina. Buenos Aires: Colihue.

Garver, J. (1993). Foreign Relations ofthe People s Republic ofChina. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Hey, J. (1993). Foreign Policy Options under Dependence: A Theoretical Evaluation with Evidence from Ecuador. Journal of Latin American Studies, 543 – 574.

Holsti, K. (2004). The state, war, and the state of war. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hudson, V. (2014). Foreign Policy Analysis. Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield.

Keohane, R., & Nye, J. (1988). Poder e interdependencia. Buenos Aires: Grupo Editor Latinoamericano.

Krugman, P., & Obstfeld, M. (2003). International Economics. Theory and Practice. Boston: Pearson Education.

Kryzanek, M. (1987). Las estrategias políticas de Estados Unidos en América Latina. Buenos Aires: Grupo Editor Latinoamericano.

Lai, H., & Kang, S.-J. (2014). Domestic Bureaucratic Politics and Chinese Foreign Policy. Journal ofContemporary China, 294-313.

Lampton, D. (2001). The Making of Chinese Foreign and Security Policy in the Era of Reform. Stanford : Stanford University Press.

Lijphart, A. (1971). Comparative Politics and the Comparative Method. The American Political Science Review, 682-693.

Miller, A. (2008). The CCP Central Committee’s Leading Small Groups. China Leadership Monitor, l-21.

Miller, C. (2000). Influencia sin poder. el desafio argentino ante los foros internacionales. Buenos Aires: Grupo Editor Latinoamericano.

Mintz, A., & Sofrin, A. (2017). Decision Making Theories in Foreign Policy Analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Morgenthau, H. (1987). Política entre las naciones. Buenos Aires: Grupo Editor Latinoamericano.

Nan, L. (2015). Top Leaders and the PLA: The Different Sty les of Jiang, Hu, and Xi. En P. Saunders, & A. Scobell, PLA Influence on China’s National Security Decision-making (p. 120-140). Stanford : Stanford University Press.

Nathan, A., & Scobell, A. (2012). China’s Search for Security. Columbia: Columbia University Press.

Ning, L. (1998). The Dynamics of Foreign-Policy Decision-making in China. Boulder: Westview.

Ning, L. (2001). The Central Leadership, Supraministry Coordinating Bodies, State Council Ministries, and the Party Department. En D. Lampton, The Making of Chinese Foreign and Security Policy in the Era of Reform (p. 39-60). Stanford : Stanford University Press.

Rosenau, J. (1966). Pre-Theories and Theories of Foreign Policy. En B. Farrell, Approaches in. Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

Russell, R. (1990). Política exterior y toma de decisiones en América Latina. Buenos Aires: Grupo Editor Latinoamericano.

Schenoni, L., & Ferrandi Aztiria, A. (2014). Actores domésticos y política exterior en Argentina y en Brasil. Confines, 113-142.

Seitz, A. M. (2007). MERCOSUR, Relaciones Internacionales y Situaciones Populistas. Argentina Global, 7-24.

Snyder, R., Bruck, H. W., & Burton, S. (1954). Decision-making as an approach to the study of international politics. Oxford: Princeton University Organizational.

Soukiassian, C. (1994). Proceso de toma de decisiones y política exterior argentina hacia Gran Bretaña. Relaciones Internacionales.

Sprout, H., & Sprout, M. (1965). Man-Milieu Relationship Hypotheses in the Context of International Politics. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Sunkel, O., & Paz, P. (1970). El subdesarrollo latinoamericano y la teoría del desarrollo. Ciudad de México: Siglo XXI.

Taiana, F. (2015). Julio Argentino Roca. Un lugar incómodo en el pensamiento nacional. Quilmes: Universidad Nacional de Quilmes.

Tao, X. (2017). Chinese Foreign Policy With Xi Jinping Characteristics. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Valenzuela, A. (1978). The Breakdown of Democratic Regimes: Chile . Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Van Klaveren, A. (2013). El análisis de la política exterior: una visión desde América Latina. En T. Legler, A. Santa Cruz, & L. Zamudio González, Introducción a las Relaciones Internacionales: América Latina y la Política Global (p. 96-109). Ciudad de México: Oxford University Press.

Waltz, K. (1979). Teoría de la política internacional. Buenos Aires: Grupo Editor Latinoamericano.

Wang, J. (2018). Xi Jinping’s ‘Major Country Diplomacy:’ A Paradigm shift? Journal of Contemporary China, 1-16.

Wang, Z. (2008). National Humiliation, History Education, and the Politics of Historical Memory: Patriotic Education Campaign in China. International Studies Quarterly, 783–806.

Zhang, Q. (2014). Towards an Integrated Theory of Chinese Foreign Policy: bringing leadership personality back in. Journal of Contemporary China, 1-21.

Zhao, Y. (2008). Reconfiguring party-state power: Market reforms, communication and control in the digital age. New York: Rowman & Littlefield.

Notes

[1] Scheme adapted and translated from Van Klaveren, 2013.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – Argentina’s Pivotal Decision

- Opinion – Javier Milei’s New Social Contract for Argentina

- Opinion – Argentina’s Javier Milei Shows his Teeth

- COVID-19 and the Economic Crisis in Argentina

- Opinion – The Civilisation Narrative: China’s Grand Strategy to Rule the World

- China-Venezuela Relations in the Context of Covid-19