Since his official arrival to the presidency of Venezuela in 2013, Nicolás Maduro has been underestimated both inside and outside his country. As the political heir to Hugo Chávez, a charismatic leader who enjoyed the benefits of history’s biggest oil boom, Maduro has had to contend with high expectations of his political performance. These expectations have not been met and Chavismo is today a discredited political movement for a significant part of Venezuelans and Latin Americans. Nonetheless, Maduro has managed to stay in power despite the collapse of the oil industry, the biggest recession in the Venezuelan economy, and opposition from much of the Western Hemisphere, including U.S. sanctions and naval presence in the Caribbean, and an obscure amphibious operation by contractors. How has this leader, without charisma and with a ruinous economy, managed to sustain the Bolivarian Revolution?

The answer to the question that motivates this essay is multifactorial. Here I summarize what my years of observation have allowed me to distinguish as keys to the survival of the Bolivarian Revolution. The first of these precedes the revolution itself and is a structural condition: Venezuela is a petro-state. Perhaps the most relevant and influential study on this type of state is The paradox of plenty… by Terry Lynn Karl, who used Venezuela as the main case study. Karl’s main finding is that petro-state institutions are severely damaged by the centralization of power that oil booms entail. Upon entering the bust phase of oil prices, the petro-state is left with centralized national authority, no institutional controls, and a fragile economy.

Karl’s finding is consistent with later works, which reaffirm the existence of obstacles, created by high oil dependency, for the establishment and stability of democracies. And although it has been shown that the oil curse is not inevitable, the case of Venezuela has been emblematic for the pathological thesis on the dependence on oil. The Venezuelan petro-state before Chávez had left a presidential office with important controls over the oil industry. Chávez himself expanded these powers through the politicization of the state-owned PDVSA (Petróleos de Venezuela), reinforcing the centralization of economic and political power in the government party and its main leaders.

This process of capturing the oil state was ideologically motivated. A normally omitted factor is that the Chavista movement is indeed a revolution that includes the components of transformation and violence that characterize them. Thus, the ideological motivation of a socialist revolution determined to transform Venezuela and challenge the global liberal order has brought about the use of all available means of the oil-state. The result has been consolidation of the assertive political movement, and evolution from a competitive authoritarian regime to one without adjectives.

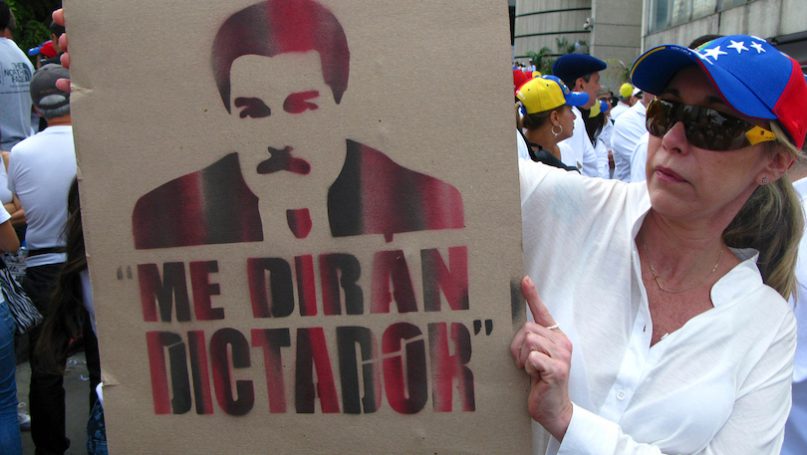

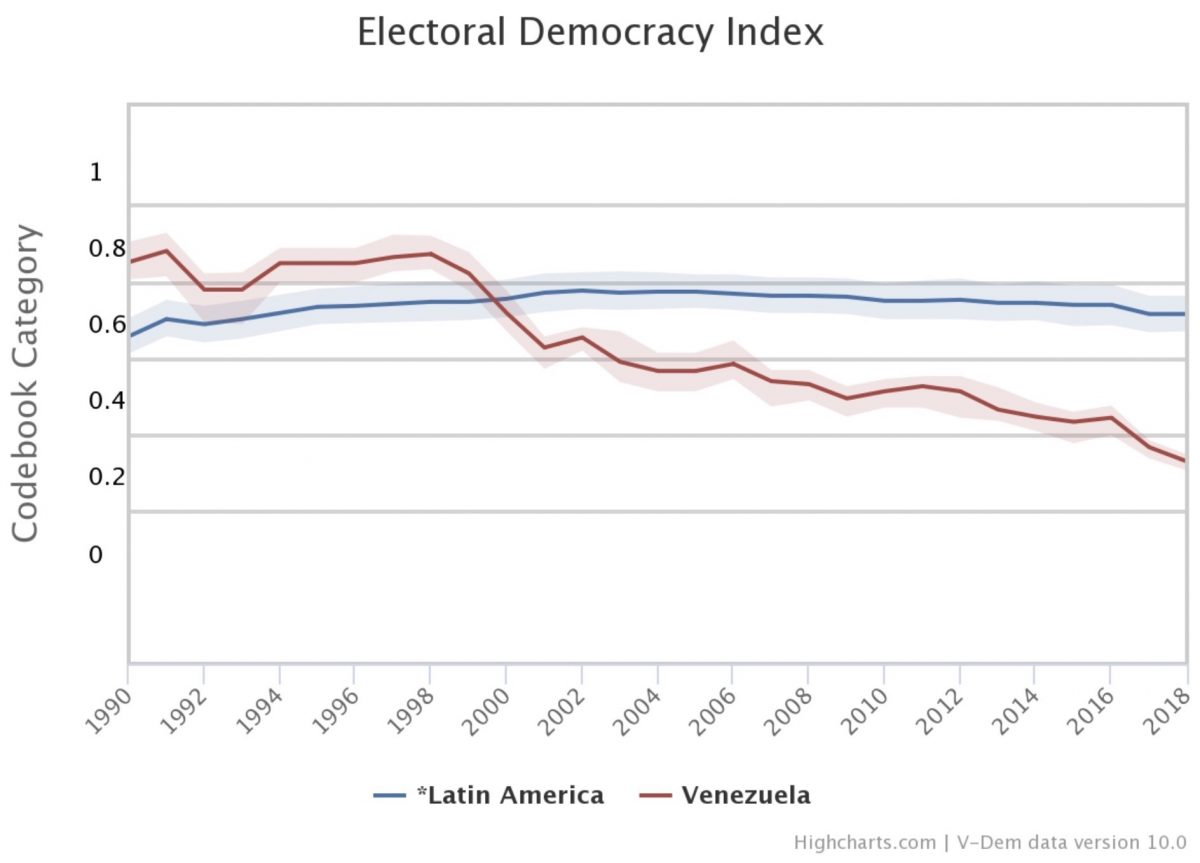

The authoritarianization trend of Chavismo is evident in the figure above, but also, a recently published investigation shows how electoral irregularities have increased, undermining institutions and suffocating the few remaining possibilities of democratic transparency in Venezuela. This, however, goes through a long process of opposition division and the construction of a tailor-made opposition by Chavismo. In his progressive authoritarian dynamic from a model of competitive authoritarianism, backed by abundant elections, an important part of the Venezuelan and world intelligentsia, and public opinion, did not automatically associate Chávez with authoritarianism. This provided significant room to maneuver to shape the opposition through a system of political and judicial rewards and punishments that have generated loyal opposition, in the style of its main ally, the Cuban regime.

For several years (1959-1999) Venezuela was indeed a historical exception in the Global South, since we see functional multiparty systems in only a few OPEC member petro-states. The combination of authoritarianism, clientelism, and neo-patrimonialism limits their democratic possibilities. In oil-exporting countries, this can translate into authoritarian stability, provided that the conditions for civil conflicts are avoided. In the Venezuelan case, Chavismo has managed to avoid a major civil conflict by alternating income distribution, when possible, and repression, when necessary. This has allowed it to have advantages in terms of power asymmetry in the attempts and negotiation processes it has faced. Thus, the Maduro regime plays with opening possibilities of negotiation or elections whenever the conditions are widely favorable.

This has been possible thanks to a long process of revolutionary civilian control over the armed forces. When Chávez was the target of an attempted overthrow in April 2002, a process of co-optation of the armed forces was activated through ideological penetration and control by intelligence bodies associated with the government party and with Cuban support. This has resulted in the persecution of military personnel who may be averse to government practices and has created coup proofing mechanisms in Venezuela, ensuring the governance of Maduro and the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV), and guaranteeing the actions of the government inside and outside the country without a realistic threat of overthrow.

These internal guarantee mechanisms have allowed Maduro’s Venezuela to continue a soft balancing policy vis-à-vis the U.S., with the support of great powers such as China and Russia. The loyalty shown by Venezuela to its Eurasian partners has allowed Maduro to have extra-regional recognition at a time when the West and most of Latin America denied his legitimacy after the 2018 irregular election. This eastward policy was born with Chávez but has been deepened by Maduro, serving as an alternative of diplomatic solidarity, a source of financial and military-technical support and, in some cases, as a mechanism to evade the sanctions imposed by Washington. This has highlighted authoritarian governance mechanisms that facilitate cooperative ties based on transnational corruption, as in the case of Russian-Venezuelan relations, especially in the energy sector.

But as the state-owned PDVSA production decreases and oil rent declines, the participation of other actors and sectors to diversify income becomes necessary. Radical rentierism related to precious and strategic metals, as well as cryptocurrencies, are part of the export basket in this increasingly informal economy. The collapse of the petro-state economy leads us to think about the possibility of a failed state, in this case, that of a failed petro-state. The alternative incomes are not effective in sustaining government spending due to their decentralized nature. But they have served to create new types of clientelist practices to satisfy the selectorate, that is, groups and individuals capable of contributing significantly to the stability or instability of a regime.

The COVID-19 pandemic must be added to the list of key factors. The Maduro government has taken advantage of the lock-down to close the already meager possibilities of social and political protest. Even in dilapidated economic conditions, the most important source of benefits for the vast majority of impoverished Venezuelans is the state. Thus, the food distribution system that has politically exploited the economic crisis becomes more important in a completely collapsed national economy. And although some scholars specialized in Latin America have raised the possibility of a scenario in which the pandemic may have favorable effects for democracy in the region, since it exposes the most authoritarian and inefficient leaderships, this does not seem to fit with the reality of Venezuela. There are no functional institutional mechanisms for the effective accountability that reinforces democracy.

Finally, the situation has exposed the underestimation of the Maduro regime by the U.S., Latin America, and much of the Western world. The Bolivarian Revolution of Venezuela and its authoritarian resilience can be interpreted as manifestations of a larger global process corresponding to the decline of the liberal order. This was perceived early by Chávez himself and motivated him to carry out a policy of defiance of what he already considered a declining order in the 1990s. Thus, embedded in the survival of Chavismo under Maduro, lie deep theoretical confusions and path dependence of Political Science and IR, which operate with a traditional, normative, and unrealistic strategic mindset that omits the aspirations and practices of emerging movements and leadership worldwide.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – Venezuela’s Migrants and the Challenges of Trinidad and Tobago

- Disputing Venezuela’s Disputes

- US-Venezuela Relations in Light of the July Election

- Venezuela: A Difficult Puzzle to Solve

- China-Venezuela Relations in the Context of Covid-19

- Regional Responses to Venezuela’s Mass Population Displacement