Since the 1960s, over 5,500 research centers have been established within Turkish universities. As of July 2025, only 573 have been closed, leaving nearly 5,000 active today. A significant number—more than 300—are thematically linked to international politics. These include 30 centers focusing specifically on the European Union (five of which were closed after 2014), around 100 dedicated to specific regions (Asia, Africa, Middle East etc.) or countries like Russia, Palestine, and Germany (11 closed), and 46 addressing migration and related issues (only four closed). More than 75 centers include the word “strategic” in their title, signaling a preference for broad, often security-oriented themes over narrower and more conventional topics such as diplomacy. Given Turkey’s role as one of the top host countries for migrants—especially after the Syrian civil war—alongside its large diaspora population in Europe, the prominence of migration-related centers is understandable. Yet, despite Turkey’s active diplomatic presence (the number of embassies etc.) and the frequency with which its leaders travel abroad, Turkish universities have shown little interest in establishing centers devoted to classical diplomacy.

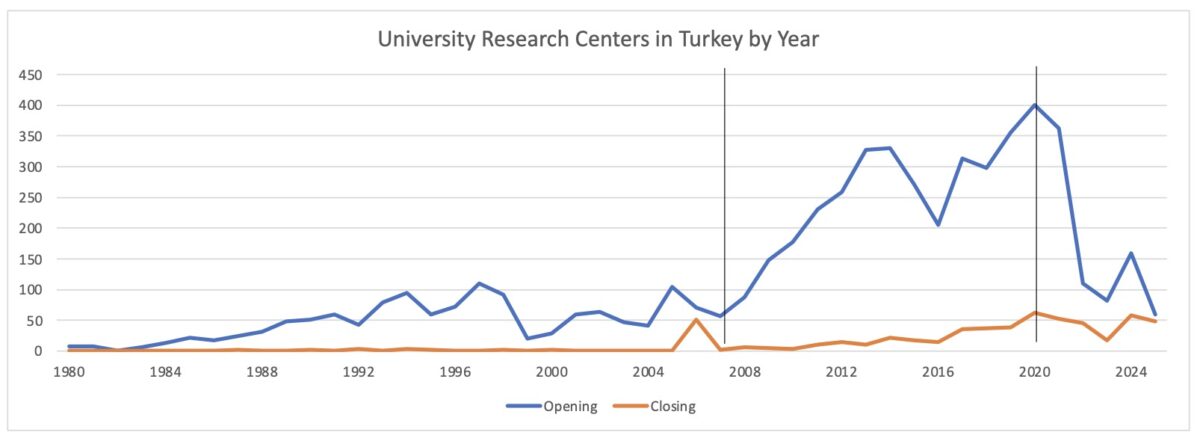

Why, then, do Turkish universities continue to open centers with broad mandates like “strategic studies” instead of focusing on more precisely defined areas as in the case of migration? One explanation lies in what can be termed a “research center inflation,” particularly evident in the surge of new centers established between 2006 and 2013. This period coincides with the rapid expansion of Turkish higher education. Many IR scholars seemingly felt compelled to establish new centers—often without a clear or focused agenda. The post-2007 era can thus be characterized as one of unchecked institutional growth. The total number of research centers jumped from approximately 1,250 in 2007 to around 2,400 by 2013. However, since 2020, this trend has reversed: fewer centers are being established, while closures have become increasingly common (see figure). Notably, while 14 new centers with “strategic” in their title were established after 2020, 7 such centers were also shut down—highlighting both the persistence and volatility of this broad thematic category. The continued absence of diplomacy-focused centers amid this institutional boom and bust raises critical questions about the thematic and intellectual priorities of Turkish academia.

It is time to critically reassess the purpose, output, and thematic focus of university research centers in Turkey, particularly those related to international politics. These centers are often closely aligned with the shifting priorities of Turkish foreign policy. For instance, the number of Africa-focused centers began to rise after 2006 and increased significantly after 2010—closely following the official designation of 2005 as “The Year of Africa” by Turkish leadership. Similarly, nearly half of the research centers devoted to the European Union were established between 2003 and 2005, a period during which EU accession was a central objective of Turkish foreign policy. Of the 31 centers focused on the Middle East, 21 were opened during the 2010s, reflecting Turkey’s heightened political engagement in the region following the Arab Spring.

These patterns clearly indicate that the establishment of research centers has been reactive to foreign policy agendas. However, this alignment has not translated into institutional interest in core themes of international politics. Despite Turkey’s proximity to several active conflict zones—particularly during and after the 2010s—only eight centers focus on peace and conflict, and one of them has been closed. Likewise, Turkey’s growing emphasis on soft power and public diplomacy in the past decade has led to the creation of only two centers dedicated to these topics. The only notable exception is the relative proliferation of migration-related centers, yet even these are primarily housed within political science departments and rarely adopt a broader IR perspective.

American universities host numerous centers and laboratories dedicated to the study and practice of diplomacy. Notable examples include the Institute for the Study of Diplomacy at Georgetown University and the Weiser Diplomacy Center at the University of Michigan. Additionally, several institutions—such as Virginia Tech, Indiana University, the University of Texas, and Purdue University—operate diplomacy labs that combine academic research with practical training. Centers focused on classical diplomacy are also common across universities in other countries, underscoring the international academic interest in this foundational aspect of international relations. In stark contrast, Turkish universities lack even a single center explicitly dedicated to the study of classical diplomacy.

This absence may be attributed to three interrelated factors. First, diplomacy in Turkey is often narrowly understood through the lens of diplomatic history—the history of relations among states—rather than as a living, evolving practice. While diplomatic history remains a standard component of undergraduate curricula, the practical aspects of diplomacy are rarely, if ever, taught. Second, Turkish IR education tends to be heavily abstract and theory-driven, often at the expense of applied or practice-oriented content. Third, studying diplomatic practices requires labor-intensive methods such as data collection, fieldwork, archival research, and elite interviews. These demands may discourage scholars who primarily conduct method-free, desk-based or literature-summary research from engaging deeply with the field.

Given that diplomacy has long remained under-institutionalized and under-explored within Turkish academic structures, there is a clear need to reconsider how it is studied, taught, and researched. While Turkish universities have shown institutional responsiveness to foreign policy shifts—establishing centers on the Middle East, Africa, and the European Union in step with evolving national priorities—they have largely ignored diplomacy itself as a coherent subject of inquiry. This omission is particularly striking given Turkey’s expansive global diplomatic presence and its active engagement in international affairs. Establishing dedicated research centers on diplomacy would not simply fill a thematic void; it would represent a vital step toward elevating the analytical and methodological standards of the IR discipline in Turkey. Such centers could help shift the field away from commentary-driven, ideologically charged discourse and toward more systematic, empirically grounded research. In what follows, I outline three interrelated reasons why Turkish universities should invest in creating diplomacy research centers—each pointing to how they could contribute to a more rigorous, relevant, and globally connected IR scholarship.

First, diplomacy constitutes one of the most resource-intensive components of Turkish foreign policy. The maintenance of embassies, consulates, and international missions—alongside the frequency of high-level foreign visits—places a considerable burden on the state budget. Yet, paradoxically, there is little systematic academic scrutiny of how these diplomatic activities are designed, justified, or evaluated. According to the Lowy Institute’s Global Diplomacy Index, Turkey possesses the third largest diplomatic network in the world, surpassed only by the United States and China. It ranks ahead of traditional great powers such as Russia, the United Kingdom, and France. Despite this vast diplomatic apparatus, there is a striking absence of empirical research analyzing its structure, strategic rationale, or operational effectiveness. A dedicated research center could address this gap by studying the organization, reach, and outcomes of Turkey’s diplomatic efforts, including its bilateral and multilateral engagements, consular networks, and foreign policy signaling.

Second, the discipline of International Relations in Turkey continues to lag behind in producing data-driven and empirically grounded research. While the number of IR scholars and publications has grown significantly in recent decades, the field remains dominated by policy commentary, descriptive accounts, and interpretative approaches, rather than systematic, replicable research. According to Aydınlı and Biltekin (2017), a striking 82,5% of IR articles published by Turkey-based scholars between 2008 and 2014 employed qualitative methods, while only 6% used inferential statistics and a mere 2% employed formal modeling. This lack of methodological diversity has stifled debate and knowledge accumulation within the community. A dedicated research center on diplomacy could directly help address this gap. By developing long-term data collection initiatives—on topics such as bilateral visits, embassy activities, treaty negotiations, or soft power engagement—such centers can generate original datasets that enable rigorous empirical research. They can also serve as institutional platforms for training scholars in advanced research methods, facilitating cross-institutional collaboration, and hosting interdisciplinary projects that combine theory with practice.

Third, Turkish IR remains entangled in abstract theorizing, ideological narratives, and policy polemics, often at the expense of systematic, evidence-based scholarship. Many scholars gravitate toward strategic studies or critical theories, favoring broad, ideational analyses that are less concerned with empirical rigor or policy evaluation. As a result, classical topics such as diplomacy, alliances, negotiation, and international institutions—core pillars of the IR discipline globally—are largely marginalized within Turkish academia. Instead of cultivating analytical depth and theoretical precision, the field frequently becomes a venue for reproducing national ideologies, endorsing conspiracy-laden accounts of world politics, or participating in short-term political debates. The proliferation of “strategic” research centers in Turkish universities reflects this tendency: they often serve as extensions of state discourse or media-driven agendas rather than as engines of independent, cumulative knowledge production. In contrast, a dedicated diplomacy research center could anchor the field in a more scientific ethos—one grounded in conceptual clarity, methodological rigor, and sustained engagement with global scholarship.

Figure 1: Annual Number of Research Center Openings and Closures in Turkish Universities (Data compiled from Resmi Gazete).

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – Turkish Foreign Policy after the 2023 Elections

- Opinion – Spain’s Request For NATO Coronavirus Aid: Will Turkey Answer?

- Religion and Secularism in Turkey, and The Turkish Elections

- The Fragility of Turkish Democracy

- Opinion – Virtual Diplomacy in India

- Tech-Diplomacy: High-Tech Driven Rhetoric to Shape National Reputation