President Trump has fundamentally upended the international order, forcing states to reassess their foreign policy alignment. In Australia, the US alliance is almost an article of faith – there is probably no policy area with stronger bipartisan support. Yet, my analysis of Australian MPs’ e-newsletters shows that MPs from the governing centre-left ALP have been conspicuously silent about President Trump, creating a significant rhetorical gap between the two major political parties in their approach to Australia’s most important ally. I argue that this silence reflects the ALP’s dilemma: the need to remain responsive to its electoral base – many of whom are hostile to Trump – while simultaneously maintaining the responsibilities that flow from the US alliance. Situating this in the broader “responsiveness vs. responsibility” debate in comparative politics offers a new way to think about how domestic political structures shape foreign policy discourse.

On 25 January 2026 Australian Senator Ralph Babet opened his e-newsletter with “America is back baby!” and spent the entirety of his e-newsletter talking about the ditching of the “woke left” and embracing of “liberty, merit and common sense”. At the other end of the political spectrum, Max Chandler-Mather (Australian Greens) wrote “It’s been a big, depressing few weeks of politics… I know many of us are concerned at the prospect of another Trump presidency.” MPs from the mainstream centre-right Liberal-National coalition (the main opposition) were a mix between cautiously welcoming his election, and active support. But what about MPs from the governing centre-left Australian Labor Party (ALP)? In their e-newsletters they were mysteriously quiet, busy burying their heads in the sand.

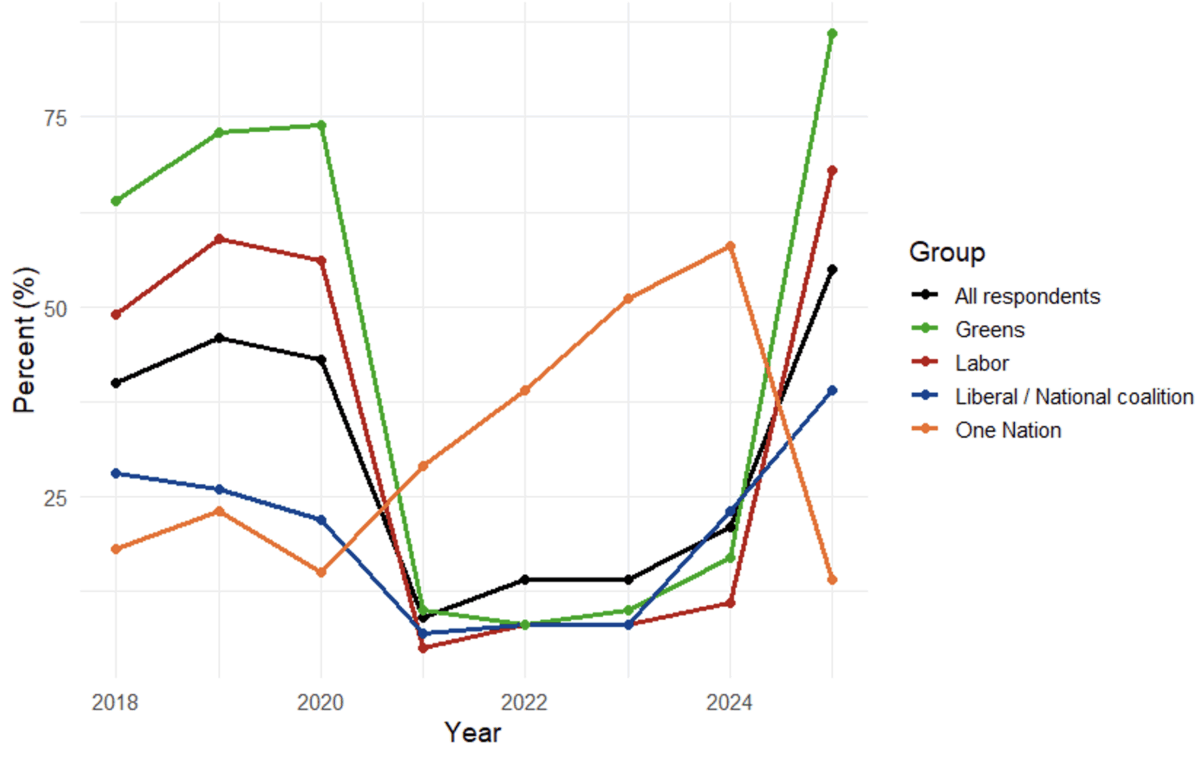

President Trump is a polarising figure across the globe, with various international studies showing that American influence has declined, with people losing trust in American leadership. This pattern is the same in Australia. The proportion of Australians expressing either “No confidence at all” or “Not too much confidence” in the US President rose from only 27% at the start of President Biden’s term (2021) to 72% at the start of President Trump’s second term (2025). Notably, this is similar to Australians’ perception of Chinese President Xi (71% expressing either “No confidence at all” or “Not too much confidence”) and only slightly better than Russian President Putin (88%).

While 55% of all respondents indicated they had “No confidence at all” in President Trump, these views differ markedly between political parties (Figure 1). Supporters of the left-wing Greens display the least confidence in President Trump, with 86% reporting “No confidence at all”, compared to 68% for the centre-left ALP. On the centre-right, the supporters of the main opposition party, the Liberal-National coalition are much less negative, with only 39% indicating “no confidence at all”. Equally important is the change over time. Looking at the Biden administration, there was a much more cross-partisan approach, with supporters of all of the major parties expressing similar views of President Biden (while One Nation supporters were much more negative about President Biden, they make up only around 9% of the electorate).

This ambivalence was also reflected across the academy and foreign policy analysts. James Curran criticised the “panicked” pundits and “the usual suspects… [who] betrayed an extraordinary lack of confidence in the American alliance” (Curran, 2025: 6), while former Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull (2025: 29) criticised the Australian political establishment for: “Want[ing] to believe that nothing has changed. That our ‘hundred years of mate-ship’… will ensure that nothing bad happens and we can ride out the four years of Trump 2.0 without undue inconvenience.”

So, how have Australian political parties responded to this significant change in public opinion? There are two competing factors, which impact parties differently. Firstly, there is the importance of being responsive to your voters and party membership. This is one of the key functions of a political party – “articulating interests, aggregating demands, translating collective preferences,” (Mair, 2009: 5). For those parties that seek to form government, there can be a separate, potentially contradictory factor – the need to act as a ‘responsible’ government. This requires parties-as-governments to “take into account (a) the long-term needs of their people… [and] (b) the claims of audiences other than the national electoral audience, including the international markets [and] the international commitments” that countries have entered into (Bardi et al., 2014: 237). Similarly, a ‘responsible’ government will act consistently with legal requirements and accepted political norms and conventions.

These two factors can conflict and present a dilemma for parties and Mair (2009) has suggested that this conflict is growing, as globalisation has increased, and states (particularly in Europe) become bound by a growing web of international commitments and obligations. The result is that “in certain circumstances the government’s hands are tied” (Karremans & Lefkofridi, 2020: 276).

Responsibility, in this context, necessitates Australia maintaining a close relationship with the USA, because of the significant level of treaty obligations and economic interdependency. While this is a bipartisan position politically, it is not a universally accepted. The USA remains our most important defence ally, and our defence posture relies on the deterrence of the US’s nuclear umbrella. There is also bipartisan support for the AUKUS agreement, Australia’s most significant defence treaty in more than 70 years. This is not saying that this is the ‘best’ foreign policy position, merely that it is the prevailing bipartisan consensus.

Given President Trump’s willingness to threaten tariffs against supposed allies who take contrary foreign policy approaches; some level of uncertainty about Trump’s commitment to AUKUS; and President Trump’s willingness to lash out at foreign politicians who criticise him, all international politicians therefore need to tread a very fine line. Turnbull (2025: 44) captured this dilemma:

If Albanese stands up to Trump… he will be attacked by both the right-wing media and the Opposition, who will say that Labor cannot get along with our most important ally. On the other hand, if he looks like a sycophant, the criticism will be that he is too weak to stand up for Australia.

As I showed before, the Liberal-National coalition and One Nation voters (the major parties of the right) are the most supportive of President Trump and the US, while voters on the left (Australian Labor Party and the Greens) were much more hostile to both President Trump and the US. This presents a challenge for the ALP between being responsive to their voters’ views and the need to maintain a relationship with the Trump Administration. It does not present a challenge for the Greens, as they do not need to be ‘responsible,’ as they have never been part of a federal government, and currently only hold 1 seat in the 150 House of Representatives. Similarly, the right-of-centre parties are not challenged, as they can be both responsive to their voters and supportive of the Australia-US alliance.

To consider how parties address this, we turn to a new dataset of e-newsletters of all Australian MPs, CanberraInbox (Casey, 2025a). Over the period March 2024 to August 2025, CanberraInbox received approximately 1700 e-newsletters from 84 MPs (just over a third of all MPs). This period includes the 2025 Australian election, as well as all the major events of the 2024 US election cycle – the RNC nomination convention (July 2024); the assassination attempt (July 2024); the election (November 2024); swearing in (January 2025); and the first 8 months of his second administration.

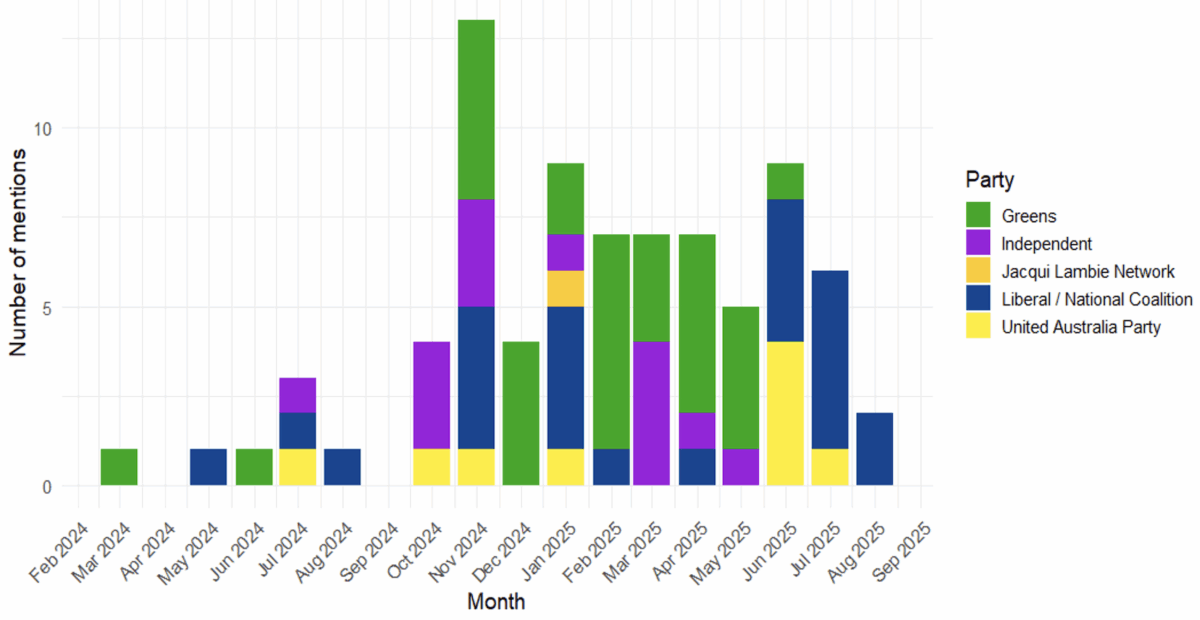

During this period, there were 80 e-newsletters from 26 MPs that mentioned President Trump, “Trumpism,” “Trumpist,” “Trump-style,” “Trump-inspired,” “Trumpian” or similar words (Figure 2). This compares to only 6 e-newsletters that mentioned President Xi, 8 that mentioned President Putin and none for our closest neighbour, Prime Minister Luxon of New Zealand. This clearly demonstrates the significance of President Trump in the e-newsletters.

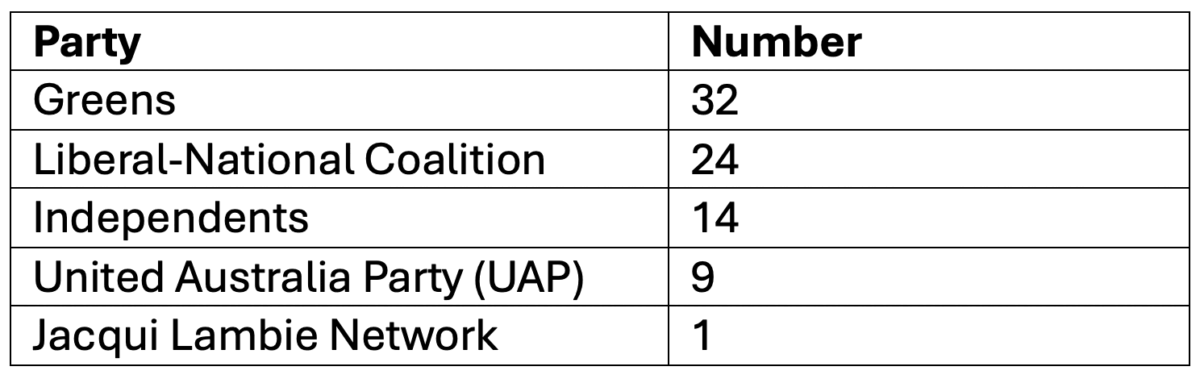

At a party level, the left-wing Greens, which make up only around 6% of our Parliament have been the most prolific (Table 1), with 32 of the 80 e-newsletters. The Greens mentioned President Trump in 25% of their e-newsletters. Outside the Greens, the most prolific writers have been Senator Ralph Babet (9), the sole MP from the United Australia Party; Senator Alex Antic (Liberal, 6); Melissa Price (Liberal, 5); Kate Chaney (Independent, 4) and Senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price (Nationals, 4). The 14 e-newsletters from independents are spread across 8 different independent MPs.

There is a natural peak in November 2024, coinciding with the US elections, and again in January 2025 with his inauguration. However, his presence continues throughout the first half of 2025, firstly with the Greens continuing to talk about him through until May 2025, and then the UAP and Liberal-National coalition continuing afterwards. Why? Because the Greens were trying to make Trump relevant to the May 2025 Australian election. The Greens’ mentions of Trump were universally negative, talking about “Trump-inspired Dutton” “Australia’s own Trump 2.0” and “Trumpian-style politics.” Their consistent approach was to link Trump to Australia’s conservative parties, for example:

I know a lot of people are anxious about what a Trump presidency in the US and a conservative LNP government here in Queensland might mean for the climate, the housing crisis, and women’s and LGBTIQA+ rights (Source: Greens MP, Stephen Bates via CanberraInbox).

It’s a shocking bill… if passed this bill will: Create a Trump-style travel ban… (Source: Greens MP, Max Chandler-Mather via CanberraInbox) (with similar language used by fellow Greens MPs Elizabeth Watson-Brown & Larissa Waters).

With a change in government in Queensland and Donald Trump in the White House again, there’s a real concern we’re heading in the wrong direction (Source: Greens MP, Elizabeth Watson-Brown via CanberraInbox).

We are on the brink of electing Peter Dutton, Australia’s own Trump 2.0 (Source: Greens MP and Leader, Adam Bandt via CanberraInbox).

I dread to think what the next few years would look like under a Trump-inspired Dutton (Source: Greens MP and Leader, Adam Bandt via CanberraInbox).

The Greens and independent MPs can afford to earn the ire of the President. They will never form government, or have to negotiate with the Trump administration, and therefore are free to energise their base. They can focus on being responsive. Significantly, none of the Greens mentioned (let alone condemned/criticised) the assassination attempt on President Trump, this is noteworthy, and indicates the degree of hostility towards Trump within this segment of the community. Surely there could have been a non-partisan position against political assassinations?

A few Australian MPs were explicitly positive about President Trump, with Senators Antic, Babet and Nampijinpa Price being the most prominent. Senator Antic talked about meeting President Trump – and then shared a photo of him with President Trump’s likeness at Madame Tussaud’s! After the election, he said that Trump’s “victory in the 2024 Presidential election is a resounding rejection of the absurdity and weakness of leftism in favour of strength, common sense, and prosperity.” Senator Babet, from the fringe United Australia Party, who received only 4% of the vote when he was elected in 2022 was gushing in his praise, “America is back baby!… The United States has entered a new golden age under President Donald Trump,” buying into his conspiracy theories, “[y]ou only need to look at how the Deep State has gone after Donald Trump,” and comparing himself to President Trump “And as long as I am in the Senate I will continue, in the words of Donald J Trump, to fight, fight, fight.”

Like the Greens, these MPs on the right of Australian politics can be responsive to their base without creating other significant risks. It is only the centre/centre-left of politics that is caught in this responsiveness-responsibility dilemma. This is not to say that ALP MPs are completely ignoring President Trump. The Prime Minister and other ministers regularly address US politics in media interviews. Similarly, ALP MPs have discussed President Trump inside parliament, but there also, they have been noticeably quieter than MPs from other parties, with only 17% of mentions of President Trump coming from ALP MPs, even though they made up 46% of the 47th Parliament (July 2022 – March 2025). This is what makes the analysis of e-newsletters particularly interesting, both because these are entirely discretionary communications, and because they are explicitly targeted at their constituency. When Trump was re-elected in 2024, both he and Prime Minister Anthony Albanese declared their confidence in a “perfect friendship” between the two countries. Yet MPs from the ALP largely chose silence, reflecting the challenge of balancing responsiveness to their voters with the responsibility of sustaining Australia’s most important alliance.

This article has shown how one segment of political communication – MPs’ e-newsletters – reveals this tension in practice. While parties on the left and right could afford to be openly critical or openly supportive of Trump, the governing ALP faced the greatest constraint, illustrating how foreign policy discourse is shaped by domestic political pressures. This finding connects to a growing body of research on the blockages to responsiveness (Casey, 2025b), suggesting that international commitments can function as another form of constraint on political parties. Of course, there are limitations. This is only one case study from one country. A comparative analysis would help refine the analysis, and exploring internal party communications would also provide important insights into how responsiveness and responsibility are negotiated behind closed doors. What the Australian case shows, however, is that one way parties attempt to manage these competing demands is simply by staying quiet – a strategy that avoids external confrontation but risks alienating their own supporters.

Figure 1. Confidence in US President: ‘No confidence at all’. Source: Lowy Institute Poll, 2025.

Figure 2. Trump mentions by party and month.

Table 1. Number of e-newsletters mentioning Trump, by party.

References

Bardi, L., Bartolini, S., & Trechsel, A. H. (2017). Responsive and responsible? The role of parties in twenty-first century politics. In The Role of Parties in Twenty-First Century Politics (pp. 1-20). Routledge.

Casey, D. (2025a) ‘CanberraInbox: Political Communication, the Personal Vote and Representation Styles—Studying Legislators’ e-Newsletters in Australia’, Legislative Studies Quarterly 50, no. 3: e70004. doi:10.1111/lsq.70004.

Casey, D. (2025b) ‘Responsiveness to the Public Opinion Expressed in Letters to Political Leaders: Insights from Australia’, Government and Opposition, pp. 1–26. doi:10.1017/gov.2025.11.

Curran, James. “Continental gift: Trump and Australia’s place in the world.” Australian Foreign Affairs 23 (2025): 6-25.

Karremans, J., & Lefkofridi, Z. (2020). Responsive versus responsible? Party democracy in times of crisis. Party Politics, 26(3), 271-279. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068818761199 (Original work published 2020)

Mair, P. (2009). Representative versus responsible government (No. 09/8). MPIfG Working Paper.

Neelam, R. (2025) Lowy Institute Poll 2025. The Lowy Institute. lowyinsitutepoll-2025.pdf

Turnbull, Malcolm. “Second coming: How to deal with Trump.” Australian Foreign Affairs 22 (2024): 24-46.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Trump, Tariffs and the Australian Federal Election

- Opinion – Getting Diversity ‘Right’ In Australia’s Nascent Space Industry Matters

- Opinion – Australia’s Recognition of Palestine as a Catalyst

- Revitalizing the Commonwealth Framework: A Political Tool for Australia and the UK?

- Opinion – Bangladesh at the Centre of Australia’s Focus on the South

- Opinion – Assessing Changes in How Australia Refers to Extremism