This is a part of the article series Decolonial Praxis: Going Beyond Empty Words, edited by Fernando David Márquez Duarte, Dulce Alarcón Payán and Javier Daniel Alarcón Mares. Editorial and Translation Assistant: Lorenia Gutiérrez Moreto Cruz.

The University is an institution that has evolved over time to fulfill various functions within society, where it is increasingly important to broaden its scope of action beyond merely transmitting theoretical and technical knowledge (De la Isla, 1991). For this reason, it is important to rethink the University not only as a space for knowledge creation and academic training, but also as an institution committed to social issues, actively involved in building citizenship, and promoting change that fosters social awareness and the implementation of projects with social incidence. Fostering synergies between teaching, research, and cultural dissemination, grounded in social commitment, facilitates the development of innovative ideas and proposals aimed to address a range of public issues, ultimately contributing to societal well-being.

In its relationship with Indigenous communities, the University holds an ethical responsibility to advocate for and protect Indigenous rights by creating institutional spaces that ensure their development, preserve their traditions, and contribute to the formulation of solutions for their specific challenges. These initiatives must honor the communities’ worldviews, avoiding the imposition of a Western perspective, fostering dialogues that promote interculturality, and respecting the knowledge, wisdom, and history of the communities.

The challenge for the University is to integrate the Indigenous perspective into all its objectives and cultivate a constructive relationship with Indigenous communities. This requires rethinking academic programs, promoting methodologies like participatory action research, collaborating with community leaders and social representatives, and addressing topics of interest such as sustainable development, self-determination, and food sovereignty, among others. Generating knowledge in collaboration with community members can not only serve as a catalyst for strengthening their capacity for self-management but also enriches academic production by incorporating a more comprehensive and diverse perspective.

In this regard, the University can play a crucial role in political and social advocacy by promoting the rights of Indigenous communities through the advancement of inclusive public policies. This social commitment enhances its position as a key actor in the political arena, where the exchange of knowledge and experiences with Indigenous communities enriches teaching and research, creating a positive feedback loop that enables the University to serve as an agent of change, contributing to social well-being.

Indigenous communities have faced violations of their rights and recognition as integral members of Mexican society, experiencing exclusion in social, economic, political, and even academic spheres (Castro Lucic, 2008). Their struggles throughout the 20th century and into the 21st century compel us, from within academia, to reconsider the ways in which we engage with them. The objective of this chapter is to reflect the importance of conducting participatory research in these communities, emphasizing the social responsibility of researchers and the University to collaborate with them, while moving away from epistemic and ontological extractivism.

This work employs a participatory methodology that actively engages the Indigenous community throughout all stages, from conception to implementation and analysis. Close collaboration with community members ensures the inclusion of their local perspectives and knowledge, thereby challenging epistemic and ontological extractivism. The central argument of this study is the need to move beyond this practices in research, emphasizing that community participation not only respects and values Indigenous knowledge but also enhances the quality and relevance of the research. The study advocates for more equitable and respectful collaboration between researchers and Indigenous communities.

This article is structured in four main sections that systematically examine the relationship between academia and Indigenous communities. The initial section contextualizes the Indigenous community of Tucta, Tabasco, and provides a comprehensive analysis of the Camellones program’s key components. Following this, the second section presents a theoretical framework examining universities’ social responsibility, emphasizing the importance of developing horizontal relationships with Indigenous communities to enhance social welfare. The third section analyzes a case study conducted in Tucta, exploring how this research initiative facilitated institutional partnerships between the community and Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana (UAM) through the Community Extension Project (PEC). This project specifically focuses on fostering equitable relationships with Indigenous, Afro-Mexican, and marginalized communities. The final section synthesizes key findings and presents critical reflections on the implications of this work.

This work is closely connected to Decolonial Praxis and theory, actively challenging colonial structures through its approach. The adopted methodology empowers the Indigenous community by ensuring their voice and autonomy are central to the research process. In line with decolonization principles, this approach seeks to transform conventional research dynamics, fostering authentic and respectful collaboration between academia and Indigenous communities. The study draws inspiration from the ideas of Linda Smith, a renowned Indigenous and Canadian scholar, whose work advocates for decolonial research approaches and encourages Indigenous researchers to critically reconsider their roles as both scholars and members of Indigenous communities.

The Indigenous Community of Tucta, Tabasco

This research focuses on the Camellones Chontales program, implemented in Tucta, one of the communities of the Chontales of Tabasco, or Yokot ‘ano ‘b (Yokot ‘anjo ‘b). Tucta is in the municipality of Nacajuca. The data presented in this section are derived from the 2010 Population and Housing Census, conducted by the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI) in Mexico, which recorded a total population of 2,015 people in Tucta. Of this population, 1,051 (52%) are men and 964 (48%) are women. Additionally, 1,600 individuals were reported to live in Indigenous households, representing 79% of the community.

In terms of basic education, 62% of the population has completed secondary or post-basic education, leaving a significant 34% without these levels of education. Additionally, only 47% of individuals aged 18 and over—out of a total of 1,282 people—have attained a secondary or higher education. It is important to highlight the disparity in educational attainment among women; only 116 women have completed their basic education compared to 274 men, and their representation in post-basic education is notably lower than that of men (INEGI, 2010).

Concerning employment levels by gender, women account for 73% of the 844 non-economically active individuals, while the non-economically active population represents 55% of those aged 12 and older. Among the economically active population, 181 individuals are unemployed, constituting a relatively high unemployment rate of 26%. In terms of healthcare services, Tucta is served by a single health center staffed by a doctor, a nurse, a social service worker—who is also responsible for health promotion—and a pharmacy manager. The health center operates Monday through Friday from 9 a.m. to 2 p.m. Regarding health coverage, data shows that 19% of the population lacks access to any health services, while Seguro Popular is the primary provider for 60% of the community. However, with the program’s termination in 2019, more than half of Tucta’s population has been left without healthcare coverage (INEGI, 2010).

The Camellones Chontales. An Experience of Self-managed Programs

The Camellones Chontales program for the exploitation of swampy for agricultural purposes, was initiated on June 28, 1977, when the President José López Portillo approved the 1977–1982 Action Plan of the General Coordination of the National Plan for Depressed Areas and Marginalized Groups (COPLAMAR) (Ovalle Fernández, 1980). The program was developed in response to the identified social problem of low socioeconomic development among the Chontal Indigenous communities in the municipality of Nacajuca. With limited employment opportunities, inconsistent income, and a lack of productive land near their place of origin, the program emerged as an innovative alternative to improve the living conditions of the Chontales of Tabasco.

The Camellones Chontales were designed to support productive activities in agriculture and fish farming. The agricultural component focused initially on the cultivation of various vegetables, including globe tomatoes, bulb onions, serrano peppers, cabbage, garlic, zucchini, cucumber, watermelon, and radish. In the fish farming component, the alligator gar was selected for cultivation. These products were intended for both self-consumption and commercial sale (Ovalle Fernández, 1980).

The program’s beneficiaries were organized into a rural society under the Social Solidarity Society (S. de SS) model, named Camellones Chontales, and registered with the National Agrarian Registry (RAN). The Social Solidarity Society Law, published on May 27, 1976, in the Official Gazette of the Federation, defines this type of organization as:

A collective entity whose members must be natural persons of Mexican nationality, including ejidatarios, community members, landless peasants, parvifundistas, and individuals with the right to work. Members contribute a portion of their labor to a social solidarity fund and are permitted to engage in commercial activities (Official Gazette of the Federation, 2018, Art. 1).

The purpose of the S. de SS is to generate employment opportunities, preserve and enhance the environment, sustainably manage natural resources, and engage in productive activities (Official Gazette of the Federation, 2018). In line with these objectives, the Camellones Chontales align well with the law, aiming to ‘achieve self-organization, self-administration, and self-financing of producers’ (Ovalle Fernández, 1980, p. 164).

The administration and governance of the Social Solidarity Society are composed of at least two entities: 1. The general assembly, which serves as the supreme authority of the society, with its resolutions binding on all members; 2. The executive committee, consisting of at least three principal members, each with an alternate, responsible for executing the general assembly’s resolutions, entering into agreements, representing the society, and performing other administrative tasks (Official Gazette of the Federation, 2018).

Tucta was the first community to benefit from the Camellones Chontales program. The construction took place in the western area of the Ramada lagoon, where a marine dredge was used to create the ridges. Organic fertilizers, such as chicken manure and cocoa husks, were applied to enrich the soil. The labor for the project was provided by community members (Pérez Sánchez, 2007).

In 2003, a tourism project was launched as part of the Biji Yokot ‘an Gastronomic, Cultural, and Craft Corridor, involving 30 camelloneros. The initiative sought to promote the area’s flora, fauna, and cultural heritage. The project included the establishment of a swimming pool, a palapa that served as a family restaurant-bar, craft stalls, and guided tours, either on foot or by canoe, allowing visitors to observe manatees. However, the project faced significant setbacks, such as the 2007 flood, which caused extensive damage and led to the disappearance of the manatees, as well as a fire that destroyed the restaurant’s palapa. These challenges, coupled with a lack of transparency regarding the profits, resulted in its gradual and eventually complete abandonment (Lara Blanco, 2016; Pérez Sánchez, 2007).

The University’s Role in Society

Contrary to certain decolonial perspectives that argue the university can consciously function to perpetuate the oppression of marginalized groups, this work adopts a view of the university as an institution with the potential to contribute to general well-being and drive social progress. While we acknowledge the critiques posed by scholars such as Castro Gómez (2007), our approach emphasizes the need to explore and amplify the university’s positive potential in fulfilling its social role. This section discusses the significance of the university’s social role and the imperative of embracing its social responsibility to generate positive impacts and foster well-being within communities.

The University can be seen as a dynamic organization that co-evolves with other entities and its socio-environmental context. Through these interactions, it continuously self-defines, self-regulates, and self-determines within the complexity of the world we inhabit (Tovar-Gálvez, 2013). In this context, the University becomes ‘a social, cultural, political, ethical-aesthetic, and cognitive arena where ideas, emotions, and projects are constantly contested, and, more importantly, where experiences, theories, and sensibilities are lived and shared’ (Tonon, 2012, p. 515). As such, its role in society has been, and continues to be, fundamental to driving major transformations through the advancement of science and technology.

More than just a center for higher education, the University serves as a space for generating knowledge, fostering research, and cultivating responsible and engaged citizens. Within these roles, building strong University-Community relationships presents a significant challenge, as it requires producing knowledge that is valuable to society—not just for the market or large corporations, as was predominantly the case in the 20th century and, to some extent, persists in the 21st century. A comprehensive transformation of the University’s functions is needed, one that prioritizes the human being and the common citizen, while contributing to the consolidation of democracy and citizenship (Tonon, 2012; Navarro-Martínez, 2018).

In a world where neoliberalism has undermined trust in the common good, collective action, and social justice—while disregarding history and championing individual freedom, even at the cost of oppressing and subjugating others (Sierra and Fallon, 2013)—the University must engage in social life and contribute to the well-being of people. To effectively influence society, the University must move beyond its laboratories and academic buildings and immerse itself in the community, where research agendas are developed with the people, not for them. In this collaborative context, various activities and projects can be undertaken to improve the quality of life of community members, preserve cultural heritage, and promote social innovation (Tonon, 2012).

Given the social role of the University, it is essential to address the concept of social responsibility. This presents a challenge, as beyond its core mission of educating new professionals and generating knowledge, the University must also contribute to societal well-being and address pressing social issues. This responsibility entails acting in an ethical and sustainable manner, fostering inclusion and diversity, and building collaborative relationships with other social actors to generate positive impacts. It also involves promoting community participation in the development and implementation of solutions (Mendoza Fernández, Jaramillo Acosta, and López Juvinao, 2020).

Universities not only shape the future by educating professionals and citizens, but also serve as key social actors and reference points, capable of driving progress, building social capital, and connecting student education with the broader social reality (Mendoza Fernández, Jaramillo Acosta, and López Juvinao, 2020, p. 98).

The social responsibility of the University is expressed in multiple ways, as it represents ‘a way of being and existing within society’ (Mendoza Fernández, Jaramillo Acosta, and López Juvinao, 2020, p. 99). Embracing this concept goes beyond ensuring equitable access to higher education for disadvantaged and marginalized groups; it also involves engaging in activities and projects that generate and disseminate knowledge, as well as implementing extension programs that bring the University’s presence into communities, actively influencing the social realities it intends to impact.

In the first instance, the University bears the responsibility of conducting socially relevant research. This means addressing the real problems and challenges faced by society through research that generates practical knowledge and concrete solutions. Socially relevant research may focus on areas such as community health, sustainable development, gender equality, social justice, and the preservation of cultural heritage, among other pertinent topics.

In the second instance, the University can fulfill its social responsibility through extension programs and community services. These initiatives should seek to transfer knowledge and resources to the community, offering support and solutions to local challenges. Examples may include health services, training and counseling, educational programs, as well as cultural and sports activities. To ensure that these extension programs remain relevant and effectively address the community’s real needs, the University must engage in ongoing dialogue and collaboration with community members, fostering a relationship of mutual learning.

The concept of linkage has gained significance in recent years, especially in discussions about the role that universities and research centers could play in addressing the major social, environmental, and economic challenges faced by the regions where they are located. A pronounced focus on ‘academicism’ has resulted in a clear separation between educational processes and the pressing issues—such as violence, environmental degradation, migration, and poverty—that large sectors of society encounter daily (Navarro-Martínez, 2018, p. 89).

The University has a fundamental social role and a responsibility toward society. By embracing its social responsibility, the University can generate a positive impact, promoting social justice, addressing real-world challenges, and shaping responsible citizens. Achieving equitable and sustainable development requires collaborative work with the community. Social responsibility is therefore an essential component of the University’s mission and purpose in the 21st century.

Organizational Changes in Universities for a More Horizontal Relationship with Indigenous Communities

Contemporary universities face the challenge of redefining their social role from a decolonial perspective to effectively contribute to the well-being of Indigenous peoples. Institutional transformation requires organizational changes that integrate the values, worldviews, and knowledge of Indigenous communities, creating spaces conducive to dialogue and the co-creation of knowledge. Non-Indigenous members of the university community must recognize the validity and importance of ancestral knowledge and actively engage in building equitable, collaborative relationships. Strengthening the university-Indigenous community bond demands concrete actions that go beyond inclusion and cultural respect, focusing on resolving specific issues and promoting structural changes in public policy, including the development of relevant regulatory frameworks.

The relationship between the University and Indigenous Communities was historically characterized by a dynamic of near-submission of the latter to the former. Early research efforts were grounded in a Eurocentric perspective aimed at ‘helping’ communities achieve progress and integrate into the capitalist market as productive members of society. This approach, coupled with the notion of Truth as derived solely through the scientific method, often marginalized or overshadowed other worldviews. As a result, a vertical relationship emerged between the University and Indigenous Communities. However, this model is no longer sustainable in the present era, as it is now recognized that we live in a complex, diverse world where alternative perspectives have valuable insights to offer about our shared reality (González Ortiz, 2011; Lezama H., 2015; Smith, 2016).

How can a horizontal relationship be established between the University and Indigenous Communities? A crucial step is for researchers and students to move away from epistemic extractivism, which involves rejecting the practice of subsuming Indigenous knowledge under Western frameworks, stripping it of its ‘political radicalism’ and ‘alternative’ critical cosmology, and then commodifying or depoliticizing it to make it more ‘romantic’ (Grosfoguel, 2016). Instead, universities must recognize and value the traditional knowledge of Indigenous communities, acknowledging its significance and embracing the possibility of coexistence and complementarity with Western academic knowledge.

The University must undertake efforts to decolonize the academic curriculum by questioning and reevaluating the dominant Western knowledge frameworks and integrating Indigenous perspectives. This can be accomplished by promoting Indigenous knowledge systems, incorporating their approaches into curricula, and including Indigenous literature and theory in reading programs. Additionally, it is important to encourage the active participation of Indigenous leaders and community members in knowledge production and academic decision-making processes.

In line with the above, the University must prioritize eliminating barriers that hinder equitable access to higher education for Indigenous students. Providing targeted support programs and scholarships, along with fostering inclusive and discrimination-free environments, are essential steps in this process. Additionally, encouraging the hiring and promotion of Indigenous staff, including faculty, researchers, and administrative personnel, and placing them in academic and leadership roles, helps to enhance representation and diversify perspectives within the institution (Smith, 2016; Macarena Ossola, 2010). This approach seeks to ensure that Indigenous members no longer…

accommodate the existing university scheme, even if they enter through special admission processes, because neither the curricula nor the academic practices have undergone substantial changes that enable them to actively participate in the organizational processes of their communities, explore the complexities of their cultures, or address the pressures of global issues affecting them today (Sierra and Fallon, 2013, p. 243).

Despite the current efforts of universities, the development of accessible and welcoming cultural spaces and resources for Indigenous communities must continue. This includes the establishment of Indigenous cultural and social centers, where events, conferences, exhibitions, and public activities can be hosted, along with libraries, specialized materials, databases managed by Indigenous communities, and community museums. Such spaces can foster interaction between the university and the community, encouraging dialogue, civic participation, and the exchange of academic and traditional knowledge. Additionally, these initiatives should aim to promote and preserve Indigenous languages and cultures by using educational materials in Indigenous languages, offering language courses at the university, and training Indigenous educators to teach language classes within their communities.

Finally, other actions aimed at achieving horizontality between the University and the Indigenous Communities is to promote the development of research work, on the one hand, and university extension, on the other. Both will be discussed later and two examples carried out at the UAM will be presented. But it should be mentioned that both are based on the collaboration and participation of the communities in all processes, seeking that the research directly benefits Indigenous communities on issues of importance, both for the community and for the university. Even more, it involves working closely with community members from the beginning of the project, respecting protocols and sharing research results in a transparent and accessible way.

It is important to emphasize that the proposed actions to create a more horizontal relationship between the University and Indigenous Communities must be grounded in the recognition that each Indigenous community is unique. Consequently, collaboration and relationships should adapt to the cultural context and specific needs of each community. Nonetheless, respect, cultural sensitivity, and open dialogue are fundamental in all cases for establishing a strong and meaningful relationship. Additionally, the University must acknowledge and address the historical and structural inequalities that have affected Indigenous communities.

The Dual Role of University Student and Indigenous Community Member

Research with social relevance is essential for the university to fulfill its social responsibility, contributing significantly to the progress and well-being of people and society in general. Here the experience of the research work titled ‘Analysis of the ‘Camellones Chontales’ program in the Indigenous community of Tucta, Tabasco will be presented. Proposal for improvement in matters of Public Policy ‘, carried out between 2019 and 2020. Likewise, it will be explained why it is important to carry out this type of research, because…

The education proposed for this century aims, among many other objectives, to foster student participation in communities through a reciprocal process, where what is learned in educational institutions (science) can be used to solve community problems, and where learning also takes place within the community itself. Viewed in this way, education becomes a reciprocal learning process in which everyone learns, and all knowledge is valued (Briceño Maldonado and Villegas Villegas, 2012, p. 35).

The research in question focused on public policy. Studies in this field aim to inform and improve public policies by evaluating government programs, analyzing social, economic, or environmental policies, and identifying effective strategies to address specific issues. Such research can provide decision-makers with evidence-based insights to tackle social challenges and enhance governance, while also empowering communities by increasing their knowledge and enabling them to participate more actively in the policymaking process.

Given the diversity of topics, socially relevant research aims to address real problems and challenges faced by communities, with a direct impact on society. Such research should have practical applications that improve the lives of individuals and communities, potentially leading to more informed public policies, effective social interventions, meaningful technological innovations, and best practices across various fields. Additionally, it requires collaboration and dialogue with relevant stakeholders from communities and other sectors of society to better align the research with the needs and perspectives of the groups involved, thereby increasing its relevance and potential for practical application. In essence, socially relevant research is crucial for the University to fulfill its role as an agent of change and progress in society.

In this context, the research on the Camellones Chontales was grounded in the recognition of the need to develop specific and cross-cutting public policies for Indigenous peoples and communities, from an alternative perspective rooted in their worldview. As Ávila Romero et al. (2016) note, ‘the knowledge of the peoples and cultures that existed, and still exist, is based on an immediate, practical, and emotional relationship with nature. This knowledge is constructed in place, it is situated or territorialized’ (p. 762). This approach acknowledges their autonomy and self-determination in rebuilding their spaces and defining their future.

Indigenous peoples have other stories to tell, which not only challenge the assumed nature of the ideals and practices they generate but also offer an alternative narrative: the history of Western research as seen through the eyes of the colonized” (Smith, 2016, p. 21).

The research was grounded in four key concepts. The first is governance and Indigenous communities, highlighting the importance of developing public policies where the role of the third sector is essential. The second concept is citizen participation, which defines the analytical framework used to examine the Camellones Chontales program. The final concept, public policies, emphasizes the creation of programs with communities rather than for them. This approach adopts a more participatory stance on public policy development and adapts the Logical Framework Methodology to ensure greater involvement of community members.

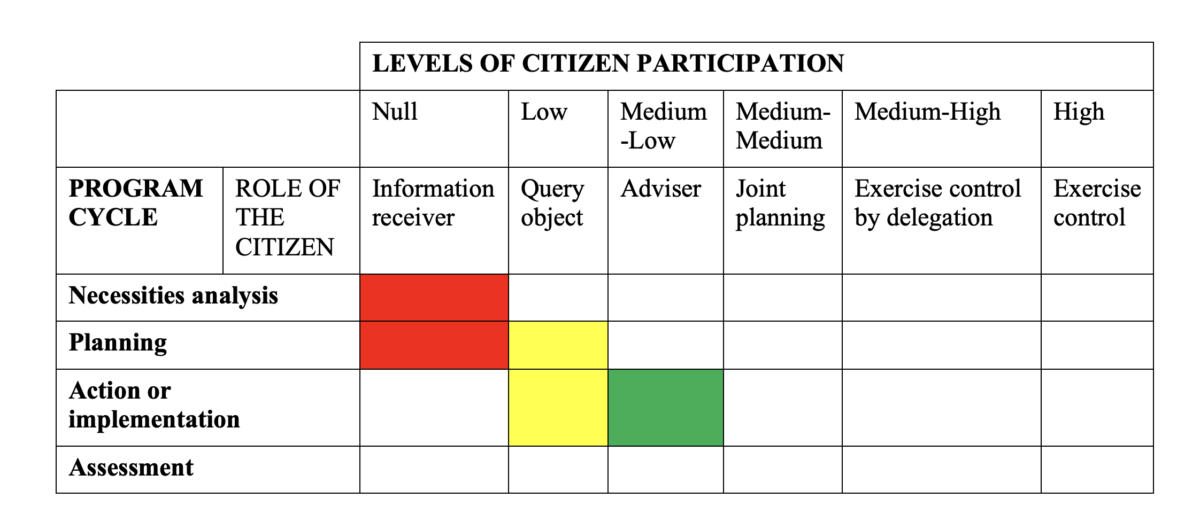

This study employs a participation matrix methodology to analyze citizen engagement, synthesizing two theoretical frameworks: Canto Chac’s (2002) participation matrix and Brager and Specht’s (1973) continuum of citizen participation, as referenced in Guillén et al. (2009). The analytical framework was specifically adapted to evaluate community involvement in the Camellones Chontales initiative. This methodological approach diverges from Canto Chac’s (2002) original conceptualization by rejecting the notion of participation as a linear progression, instead recognizing its dynamic nature across different program phases. While Canto Chac’s model effectively delineates citizens’ roles in policy and program development, it does not explicitly categorize participation levels. The integration of Brager and Specht’s (1973) participation continuum addresses this limitation by providing a structured framework for role identification. The resulting analytical tool incorporates additional intermediate levels, offering a more nuanced and comprehensive assessment of the participation spectrum.

The analysis of citizen participation in the development of the Camellones Chontales program was grounded in discussions and input from various community members. Based on the participation matrix (Table 1), the level of involvement of program beneficiaries can be identified across different stages, including the project, self-consumption, marketing, and tourism phases. The findings indicate that participation was generally low, posing a challenge for the community due to a lack of knowledge about managing non-organic agricultural products unfamiliar to the region, as well as insufficient training in administrative and organizational matters.

Methodologically, this investigation employed a multi-phase analytical approach combining focus group data with structural analysis tools. The diagnostic process utilized a Motricity and Dependency matrix coupled with Cartesian plane analysis, revealing four critical variables for examination. Through the application of a Problem Priority Diagram, the investigation identified the primary challenge as ‘cessation of productive activities in the Camellones Chontales.’ This finding informed the establishment of the central research objective: enhancing productive engagement within the Camellones Chontales system. The systematic analysis yielded five strategic interventions:

- Provide more public lighting in the Camellones Chontales area;

- Place surveillance means in the area;

- Provide accountability training;

- Provide legal training;

- Promote internal organization.

These activities would help establish a safe zone in the Camellones Chontales area, enhance the culture of accountability among the camelloneros, and create an internal regulatory framework for their activities. Collectively, these measures aim to reduce unemployment in Indigenous communities, particularly in Tucta. This proposal emerged from a collaborative and respectful process that engaged both researchers and community members.

Furthermore, this activity promoted increased participation among Indigenous community members in the development of public policies and programs. The decision-making processes were designed to be inclusive, respecting the community’s perspectives and knowledge while providing ample opportunities for involvement. This approach involved recognizing and strengthening the community’s resources, skills, and capacities to effectively identify solutions to their challenges.

This research aligns with the necessity of implementing culturally appropriate and relevant social programs for Indigenous communities. It is essential to consider their specific values, practices, and needs, adapting approaches and content accordingly. Collaborating with the Indigenous community can facilitate the identification of more effective and culturally sensitive strategies for addressing social challenges.

A key priority is developing targeted training programs for Indigenous community members in essential areas such as community leadership, project management, group facilitation, and business skills—competencies crucial for community empowerment and self-determination. Equally important is the implementation of robust monitoring and evaluation systems that allow both the Indigenous community and the University to assess program effectiveness and impact through continuous feedback loops.

This initiative led to the formation of new alliances and collaborations between the University, the Indigenous community, and other relevant organizations, such as government agencies, non-governmental organizations, and civil society institutions, aimed at expanding the scope and impact of social programs. This resulted in a connection with the Community Extension Project (PEC) of UAM.

To summarize, socially relevant research in Indigenous communities plays a crucial role in their well-being and sustainable development. Such research goes beyond merely generating academic knowledge; it is grounded in the needs and priorities of Indigenous communities and aims to address the challenges and inequalities they face. This approach helps to mitigate the skepticism that Indigenous communities often harbor toward research.

The belief that research will ‘benefit humanity’ reflects a strong sense of social responsibility. However, the issue with this belief is that Indigenous peoples are often extremely cynical about the ability, motives, and methodologies of Western research to provide any real benefits to them, as this science has historically viewed them as ‘non-human’ beings and, in fact, has classified them as such (Smith, 2016, p. 165).

The social relevance of this type of research lies in its inclusive, participatory, and respectful approach toward Indigenous communities. It is founded on a collaborative and dialogic relationship between researchers and communities, recognizing traditional knowledge and Indigenous perspectives as valuable assets. Moreover, socially relevant research aims to create a tangible positive impact on the lives of Indigenous communities, but it must be conducted within ethical frameworks that are culturally appropriate and respectful of the rights and autonomy of these communities. Researchers should acknowledge their role as guests on Indigenous territory and work closely with community members to ensure that research processes are inclusive and honor cultural protocols and Indigenous values.

Building Bridges: The Community Extension Project

The development of socially relevant research is one of the actions that universities in Mexico can undertake to establish more horizontal and collaborative relationships with Indigenous communities. Another significant initiative is university engagement, which not only helps to bring visibility to these populations and their challenges but also facilitates the co-construction of solutions that respect their knowledge and realities (Navarro-Martínez, 2018). This subsection analyzes the Community Extension Project (PEC) of the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana (UAM) as an example of this approach, illustrating how the horizontal relationship with communities—particularly with Tucta and its Camellones Chontales—has been pivotal in the development of institutional projects that integrate both academic research and community work.

The Community Extension Project (PEC) was established in 2013 with the purpose of fostering an authentic and horizontal relationship with communities, promoting the University’s social responsibility while creating a space where students and faculty can drive research and initiatives that benefit social well-being. This project brings together a multidisciplinary group of faculty from various academic units at UAM to collaborate on municipal and community initiatives in marginalized areas, particularly within Indigenous and Afro-Mexican communities. To implement and monitor its projects, the PEC employs two primary methods: 1) the Logical Framework Methodology and 2) the action-research method. Additionally, it categorizes its projects into three areas of collaboration: 1) ecological, 2) productive, and 3) social and educational (Community Extension Project, personal communication, June 28, 2023).

In this context, the PEC distinguishes itself from traditional university extension, which typically involves a one-way transfer of knowledge and resources to the community. While well-intentioned, this approach often prioritizes scientific knowledge over local wisdom, undervaluing the worldviews and knowledge inherent to Indigenous and Afro-Mexican communities (González Ortiz, 2011). In contrast, the PEC embraces a model of dialogue and co-construction, where the community actively participates in decision-making and project design, thereby allowing scientific knowledge and community wisdom to enrich one another. This collaboration not only provides solutions to specific problems but also strengthens cultural identity and promotes community autonomy.

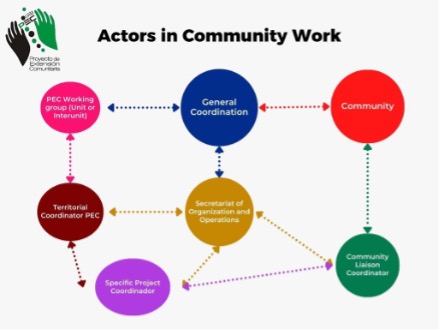

The PEC operates based on two key moments in its engagement with communities. The first is the process of outreach and trust-building with local actors, who play a crucial role in connecting with the communities. In the case of Tucta, this initial engagement has been facilitated by an understanding of the region and its challenges, enabling the identification of specific needs and opportunities for collaboration in the Camellones Chontales. Figure 1 illustrates the framework of actors involved in this process, highlighting the role of the PEC coordinator as an intermediary between the communities and university working groups, while the Secretary of Organization and Operations oversees the individual efforts of faculty members and coordinators of specific projects.

The second crucial moment is the participatory needs assessment, which identifies the areas where the University can effectively contribute. This assessment not only guides the projects but also involves community participation, incorporating their perceptions and local knowledge for greater impact. In the case of Tucta, opportunities were identified for training workshops in fish farming and land recovery in the camellones, alongside training in administrative and organizational skills. However, the COVID-19 pandemic interrupted the initial implementation efforts, prompting a resumption of discussions in 2023 to re-establish the connection, with the understanding that in-person collaboration is essential for strengthening trust.

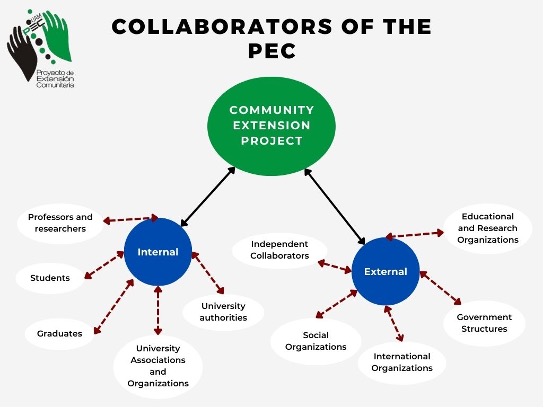

The PEC also engages with external actors beyond the university, recognizing that collaborative work requires the integration of multiple stakeholders, including educational, social, and international organizations, as well as government authorities. Figure 2 illustrates the network of collaborators interacting with the community of Tucta and other PEC projects, adapting their interventions to the specific context of each community and fostering genuine dialogue that respects their knowledge and expertise.

The engagement with the community of Tucta and the Camellones Chontales reflects a transformative approach to university extension. This model recognizes the university’s capacity as a strategic partner rather than a unilateral agent of change, promoting co-construction and respect for local culture and knowledge. However, it also faces challenges, such as the need for sustained funding to facilitate in-person visits, which are essential for strengthening collaboration and preventing the relationship from being limited to insufficient virtual exchanges.

The University extension in Indigenous communities, as exemplified by the PEC’s collaboration with Tucta, proves to be a powerful tool for promoting inclusion, sustainable development, and the strengthening of cultural identity. By establishing a relationship based on respect and horizontal dialogue, the university can effectively address local needs and aspirations, driving both scientific knowledge and community wisdom toward a common goal: the comprehensive well-being of Indigenous communities. This commitment to social relevance and ethical responsibility reinforces the university’s role as an active participant in building a more equitable society that respects cultural diversity.

Final Observations

This study analyzed the design of the program to identify areas of opportunity, with a significant finding being the participation of stakeholders—both state and civil society—that support the community’s success. The analysis highlighted the necessity of integrating these communities, particularly Indigenous populations, into the formulation, design, implementation, and evaluation phases of public policy. Additionally, this text invites reflection on the following five elements:

First: Alternative Epistemologies and Indigenous Knowledge Systems. A fundamental paradigm shift is required in the methodological approach to Indigenous studies, one that acknowledges and respects Indigenous communities’ autonomy and self-determination while recognizing their dynamic interactions within broader social contexts. This reconceptualization necessitates moving beyond traditional observational research paradigms toward a more nuanced engagement that embraces epistemological pluralism and validates diverse knowledge systems. The researcher’s role must evolve from that of a distant observer to that of an engaged scholar who demonstrates cultural competency, intellectual humility, and profound respect for Indigenous ways of knowing and being. This approach recognizes that Indigenous knowledge systems represent sophisticated theoretical frameworks developed through generations of empirical observation and collective wisdom.

Second: The Dual Role of the Indigenous Researcher. Indigenous researchers occupy a unique epistemological space that necessitates critical reflection on their multifaceted identity and responsibilities as both academic investigators and community members. Their distinctive position engenders heightened social and ethical obligations, as they navigate between insider and outsider perspectives within their communities. This dual positionality enables them to synthesize Indigenous and academic knowledge systems, facilitating nuanced understanding of community dynamics while serving as cultural mediators in the construction of cross-cultural dialogue. Their role transcends traditional research boundaries, creating opportunities for meaningful knowledge exchange between academic institutions and Indigenous communities, while simultaneously maintaining cultural integrity and academic rigor.

Third: The University’s Role as a Catalyst for Social Transformation. Academic institutions must fundamentally reexamine and strengthen their commitment to Indigenous, Afro-Mexican, and marginalized communities through the promotion of endogenous development initiatives and meaningful community engagement. This engagement should emphasize the co-creation of collective knowledge and collaborative solutions to pressing social challenges. While university extension programs serve as vital mechanisms for achieving these objectives, resource constraints—particularly related to field research and community outreach activities—often impede comprehensive engagement with communities and thorough understanding of their lived experiences. Despite these limitations, universities must prioritize sustainable partnerships that recognize and integrate local knowledge systems while fostering participatory approaches to community development.

Fourth: The Importance of the PEC. This university program acknowledges the complexity of communities, characterized by diverse worldviews, sociopolitical dynamics, and technological limitations. Nevertheless, it is committed to addressing microsocial issues through organizations that serve as vehicles for establishing social order and enhancing the University-Community relationship.

Fifth: The Indigenous Community-University Partnership. The university plays a pivotal role in rebuilding and maintaining trust with Indigenous communities. Historical experiences have left many Indigenous community members feeling marginalized by academic institutions, particularly when research conducted within their territories appears primarily motivated by academic credentials or funding requirements rather than community benefit. Indigenous communities seek tangible improvements in their quality of life and value meaningful partnerships with researchers who demonstrate authentic commitment to their well-being. Therefore, it is imperative that research transcends mere academic documentation and generates substantive social impact while fostering sustainable, reciprocal relationships between universities and Indigenous communities. Researchers must thus serve as bridge-builders, facilitating meaningful dialogue and collaborative partnerships between academic institutions and Indigenous peoples.

References

Lezama H., Elizabeth M. 2015. Interacción universidad-comunidad: La articulación estratégica de la UNEXPO Puerto Ordaz con la siderurgica del Orinoco y Pulpaca en el servicio comunitario. Revista Orinoco Pensamiento y Praxis (6): 1–21.

Ávila Romero, León Enrique, Alberto Betancourt Posada, Gabriela Arias Hernández, y Agustín Ávila Romero. 2016. Vinculación comunitaria y diálogo de saberes en la educación superior intercultural en México. Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa 21 (70): 759–783.

Briceño Maldonado, Yrinilde del Carmen, y Alberto Villegas Villegas. 2012. Vínculo Universidad-Comunidad en la Universidad de Los Andes, Núcleo Rafael Rangel (Trujillo). Educere 16 (54): 33–42.

De la Isla, Carlos. 1991. La Universidad: conciencia crítica. Estudios 69–76.

Diario Oficial de la Federación. 2018. Ley de sociedades de solidaridad social. Ciudad de México, 27 de mayo.

González Ortiz, Felipe. 2011. La vinculación universitaria en el modelo de educación superior intercultural en México. La experiencia de un proyecto. Revista de Sociedad, Cultura y Desarrollo Sustentable 7 (3): 381–394.

Grosfoguel, Ramón. 2016. Del <<extractivismo económico>> al <<extractivismo epistémico>> y al <<extractivismo ontológico>>: una forma destructiva de conocer, ser y estar en el mundo. Tabula Rasa (24): 123–143.

H. Ayuntamiento Constitucional de Nacajuca. 2019. Plan Municipal de Desarrollo Nacajuca.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. 2010. Censo de Población y Vivienda.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. 2016. Censo Nacional de Población y Vivienda.

Macarena Ossola, María. 2010. Pueblos indígenas y Educación Superior. Reflexiones a partir de una experiencia de jóvenes wichí en la Universidad Nacional de Salta (Salta, Argentina). Revista ISEES (8): 87–105.

Mendoza Fernández, Darcy Luz, Martha Cecilia Jaramillo Acosta, y Danny Daniel López Juvinao. 2020. Responsabilidad social de la Universidad de La Guajira respecto a las comunidades indígenas. Revista de Ciencias Sociales XXVI (2): 95–106.

Navarro-Martínez, Sergio Iván. 2018. Perspectivas y alcances de la vinculación comunitaria. El caso de la Universidad Intercultural de Chiapas, unidad Oxchuc. Revista LiminaR. Estudios Sociales y Humanísticos XVI (1): 88–102.

Ovalle Fernández, Ignacio. 1980. Camellones Chontales: proyecto para la explotación de zonas pantanosas. México: Instituto Nacional Indigenista.

Pérez Sánchez, José Manuel. 2007. Desarrollo local en el trópico mexicano. Los camellones chontales de Tucta, Tabasco. México: Universidad Iberoamericana.

Sierra, Zayda, y Gerald Fallon. 2013. Entretejiendo comunidades y universidades: desafíos epistemológicos actuales. Ra-Ximhai 9 (2): 235–259.

Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. 2016. A descolonizar las metodologías. Traducido por Kathyn Lehman. Santiago de Chile: LOM Ediciones.

Tonon, Graciela. 2012. Las relaciones universidad-comunidad: un espacio de reconfiguración de lo público. Polis, Revista de la Universidad Bolivariana 11 (32): 511–520.

Tovar-Gálvez, Julio César. 2013. Relaciones entre universidad y comunidades: hacia un currículo de educación ambiental contextualizado. Revista del CESLA (16): 109–122.

Figures and Tables

Table 1: Levels of Citizen Participation in the Camellones Chontales Program

Souce: Own elaboration

Figure 1

Actors of community work in the PEC

Source:Community Extension Project (personal communication, June 28, 2023).

Figure 2

PEC collaborators

Source: Community Extension Project (personal communication, June 28, 2023).

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Critical Consciousness Development through Indigenous Public Consultation in Baja California

- Indigenous Cosmographies: The Narratives of the Kukama Kukamiria of Peru

- Opinion – The Pope’s Apology for Indigenous Residential Schools

- Pluriversal Technologies: Innovation Inspired by Indigenous Worldviews

- Devouring Brazilian Modernism: The Rise of Contemporary Indigenous Art

- What is Decolonial Praxis?