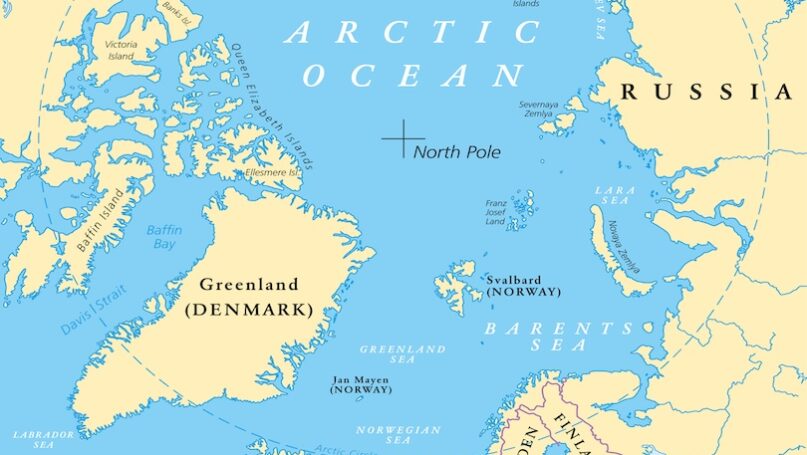

Russia’s Northern Sea Route (NSR) along its Arctic coastline has, for centuries, been as much a dream as a reality. The coastal corridor is a chance to cement Russia’s place as a polar energy superpower, and the presence of unexploited reserves of resources, the keeper of a possibly vital global artery. Yet the NSR’s story in the 21st century is not simply about ambition. It is about a paradox; two forces pushing in opposite directions. One force is geopolitical. A tightening of Western sanctions has cut Russia off from Western capital, technology, and partners that once underpinned its Arctic rise. The other is environmental: climate change. The melting of the sea ice at unprecedented rates is lengthening the navigable season and giving Russia a window of opportunity in the high north. Together they create a strange, almost theatrical tension – a stage where climate change is opening new Arctic pathways even as geopolitics seems to be closing them. This article traces how Moscow has adapted awkwardly at times and creatively at others to this paradox.

The question is not whether Moscow still wants to realise the NSR’s promise. It does. The question is whether it can, and if so, at what cost. The answer lies in how Russia has substituted partners, improvised workarounds, looked inwards for domestic substitutions and leaned on risky logistics to keep its Arctic ambitions alive. The years after 2007 (to capture the pre-sanctions baseline and the waves of sanctions that followed), when Russia planted a titanium flag on the seabed at the North Pole, tell a story of Russia’s NSR adaptation, dependency, and resilience under constraint.

The NSR’s economy runs on the same plumbing that moves everything from coffee to crude: finance, insurance, classification societies, maritime services, and high-end technology. When Western governments began sanctioning Russia over Crimea in 2014, the sanctions did not simply target individuals or issue symbolic bans. They went for the “nodes” in the global economy that Russia’s Arctic projects depended upon. This is a textbook case of weaponised interdependence. The theory explains how states that control critical financial and technological chokepoints in an interconnected global order can turn global connectivity into leverage. The effect was immediate. U.S. export controls banned Arctic offshore oil exploration technology, freezing ventures like ExxonMobil’s Kara Sea project. European and American banks withdrew. Insurers cancelled coverage for Russian vessels, and the International Association of Classification Societies expelled Russia’s maritime register. Without classification, many Russian-controlled ships lost their safety certificates and lost access to ports and insurance altogether.

The 2022 invasion of Ukraine supercharged this process. Energy giants such as Exxon, and Halliburton left Russia’s Arctic. Sanctions extended to almost every aspect of maritime trade. International Protection & Indemnity (P&I) clubs refused Russian risks, and the exodus of foreign expertise left Russia’s Arctic sector without many of the specialised tools it had once imported. In essence, sanctions acted as a structural stress test on Russia’s Arctic political economy, which raised financing costs, choking technology transfer, and narrowing partnership options for both upstream oil and gas exploration and midstream shipping and processing. Yet, the sanctions did not halt Arctic operations altogether. By 2023, the NSR cargo carried record volumes along the route. The moved cargo was roughly around 38 million tonnes of goods in 2024. This cargo was almost entirely Russian oil, gas, and minerals headed to Asia. The international shipping firms that had once dreamed of using the NSR as a global transit lane were seemingly gone. What remained was a “Russified” corridor: an export pipeline to friendly markets, sealed off from most of the world.

Sanctions forced Russia to find replacements for Western finance, expertise, equipment, and markets. The most obvious substitute was China. The two countries already had growing energy ties, and after 2014, Beijing stepped in where the West stepped out. Chinese state banks provided roughly $12 billion in loans after Western financing dried up for Yamal LNG, the Arctic’s first LNG megaproject. China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) took a 20% stake in the project in 2013, and the Silk Road Fund took another 9.9% in 2016. Chinese shipyards supplied modular components, and by late 2017, the project was completed on schedule despite the constraints. This model, to replace Western inputs with Chinese ones, was carried over to Arctic LNG 2 on the Gydan Peninsula. CNPC and CNOOC each took 10% stakes by 2019, and Chinese yards again won construction contracts. A secondary interdependence formed: Chinese capital, shipbuilding, and market demand for LNG in exchange for Russian resources and Arctic access.

But this substitution came with a catch. The relationship was asymmetric interdependence. Russia now relies far more on China than China does on Russia. For Moscow, the NSR and Arctic LNG capacity are strategic lifelines and Russia, under sanction, cannot so easily diversify its partners. But Beijing has other suppliers; the NSR is optional for Chinese trade. Beijing has used that leverage with a light but unmistakable touch by pressing for sanctions carve-outs and pausing when penalties threaten its global financial and commercial interests. When Washington sanctioned Arctic LNG 2 in late 2023, Chinese firms froze participation. CNPC and CNOOC invoked force majeure, and Wison (a Chinese manufacturer of LNG modules) recalled shipments and stopped work altogether. By 2023, roughly 95% of NSR transit cargo was bilateral Russia–China trade, mostly Russian oil moving east. When China pulled back, Moscow protested mildly; when Western firms did the same, the rhetoric was far harsher. The imbalance was clear. The NSR had become a lifeline for Russia, but only one option among many for China.

Alongside external partnerships, Moscow sought to fill the gaps domestically. The flagship is the Zvezda shipyard in the Russian Far East, which was meant to deliver a homegrown fleet of Arctic-class tankers and LNG carriers. Initially a joint venture with South Korea’s Samsung Heavy Industries, Zvezda lost access to many suppliers after 2022. Building the specialised Arc7 LNG tankers proved harder than planned, and delays created a shipping shortfall. So, Moscow improvised at sea. The workaround was a fleet few had anticipated: the so-called “shadow fleet.” These are ageing, often 20-year-old tankers. Reflagged under flags of convenience to Panama, Liberia and the Marshall Islands, they sail without reputable insurance or up-to-date safety certification. After the EU banned Russian oil imports and the G7 imposed a price cap, Russia’s traders bought up and reactivated such ships. Some sail with AIS trackers off, earning them the nickname “floating time bombs” from former NATO commander James Stavridis.

Regulators noticed. NATO began monitoring the dark fleet in 2023. The UK and Denmark tightened port inspections earlier; by mid-2025, Norway ordered inspections of all foreign tankers using its ports that had been involved in Russian Arctic trade. The cat-and-mouse is literal: AIS “spoofing,” loitering near transhipment points like Murmansk, and identity-masking tactics have all proliferated. The objective is simple – keep exports moving despite Western control over finance and insurance chokepoints. The method is naturally costly and risky.

The environmental risks are also obvious, especially in Arctic waters. Yet by 2023, this shadow fleet had helped Russia stage a dramatic comeback on the NSR. Transit cargo, which had collapsed to around 41,000 tonnes in 2022, hit a record 2.1 million tonnes in 2023, much of it oil to China. Of the 75 transit voyages (the most ever in a season) that year, 59 were in ships over 10 years old, and nearly 40% in vessels over 20. Three voyages were made by ships with no ice classification at all, possible only during the mildest late-summer window. This is resilience under constraint in action: maintaining volumes, but through seemingly riskier, costlier, and less sustainable logistics.

The paradox deepens when nature itself becomes a player. The Arctic is warming roughly four times faster than the global average, a phenomenon known as Arctic amplification. This is thinning and shrinking its sea ice. Late-summer ice extent has declined by about 12% per decade, and the September ice volume is almost half of what it was in 1980. In a warm year like 2020, the NSR can see up to 88 ice-free days, extending the season well into October. The distance savings are tempting. After the 2021 Suez blockage, Moscow pitched the NSR as the more sustainable and safer, with President Vladimir Putin setting targets of 80 million tonnes of cargo by 2024 and 130 million by 2035. Russia invested in infrastructure to shape the Arctic in its favour. Chief among those investments is the series of nuclear icebreakers in the LK-60Ya class, intended to widen and lengthen the navigable seasonal window.

Variability is the Arctic’s constant. In 2021, an early freeze trapped more than 20 ships in the Laptev Sea. A single harsh season or geopolitical flare-up could, according to one modelling study, cost up to $10 billion by closing the route for a year. Wind and currents can push ice into chokepoints, while storms and fog add further hazards. The message: averages entice; outliers punish. Major shipping companies remain unconvinced. The IMO’s Polar Code demands expensive safety upgrades, and giants like CMA CGM have sworn off the NSR, citing environmental and reliability concerns. Arctic shipping is feasible but rarely profitable for time-sensitive cargo under current conditions. In effect, climate change is lengthening the season but not guaranteeing it. Warm years can soften the impact of sanctions by enabling marginal ships to sail; cold years can erase those gains overnight.

Moscow treats most of the route as water where it can write its rules with Russian regulations. The legal scaffolding rests on UNCLOS Article 234. The clause gives coastal states extra authority over ice-covered waters to protect the environment and, in places, on claims of historic usage through narrow straits. That interpretation has teeth. In 2019, Russia demanded advance notice from foreign warships before NSR transits. In 2023, Russia proposed stretching that notice to 90 days. The counter-view in Western capitals is blunt: key passages function as international straits with transit rights. Call it legal geopolitics. The idea that in contested spaces, law becomes an instrument of statecraft.

With Western commercial presence all but gone since 2022, there have been few real-world tests of those competing claims. The ambiguity persists. So does the risk of friction if NATO navies decide to test freedom-of-navigation in the high north. The Arctic Council was built to keep geopolitics off the ice. War changed that. In early 2022, seven of eight members (everyone but Russia) paused participation, sidelining Russia’s chairmanship. Work resumed later that year without Russia; when Norway took the chair in 2023, that format stuck. The result: a governance gap where the Council once supplied common ground on search-and-rescue, spill response, and scientific cooperation. Into that gap have flowed unilateral and minilateral moves: EU sanctions to enforce oil price caps, national inspections of suspect tankers, NATO’s higher Arctic profile, and Russian military investments through the Northern Fleet. Moscow has doubled down on bilateralism, notably with China under a “Polar Silk Road” banner. Remove a pan-Arctic consensus, and states start to read the NSR less as a shared commercial asset and more as a strategic corridor. As long as the Council stays divided and the law stays fuzzy, the NSR looks less like a future global lane and more like a national project under duress.

One under-appreciated dynamic is how weather and policy interact. A warm, low-ice year can partially offset sanctions by letting Russia move more cargo with sub-optimal ships and fewer partners. A harsh ice year can erase those workarounds; no amount of reflagging gets a thin hull through new ice without icebreakers. 2023 offered mild late-summer conditions and newly assembled logistics. Hence, the record season. 2021 offered an early freeze that embarrassed seasoned operators. Climate acts as the swing variable in Russia’s resilience equation. Targets mirror the tension. 80 million tonnes by 2024 proved aspirational as sanctions deepened and ice conditions fluctuated. The reset to 130 million by 2035 admits the need for a longer runway. More LK-60Ya icebreakers, more Arc7 hulls, more trans-shipment capacity, and, crucially, more reliable partners. The Zvezda bet may pay off, but replacing the full Western stack in the form of financing, kit, and specialised metallurgy takes time that geopolitics rarely grants.

The shadow fleet moves oil, but at a cost. Older hulls, opaque ownership, weak insurance, and AIS dark zones each raise the chance of an incident. The high north does not forgive. A significant spill by an unclassed or uninsured vessel could slam shut political windows that the climate has opened. Every accident, real or narrowly avoided, argues for more scrutiny. For non-Russian shippers, reputational and compliance risk is decisive. The safety problem is moral, ecological and financial. Insurance premiums, capital costs, and compliance burdens spike when standards look variable and enforcement is vigilant.

If the NSR is to attract rather than deter global carriers, four shifts stand out. The first is stable multilateralism. A thaw in Arctic Council politics that restores full eight-member cooperation on search-and-rescue, spill response, and scientific collaboration would reduce risk premiums. Without it, patchwork national rules and military signalling will continue to overshadow commercial priorities. The second is legal clarity. Narrowing the gap between Russia’s interpretation of Article 234 and Western views on straits rights, whether through litigation, negotiated guidelines, or pragmatic practice, would help calm the concerns of navies and insurers. Ambiguity, in this case, is costly. The third is infrastructure at scale. Expanding the fleet of LK-60Ya icebreakers, deepening the Arc7 fleet, ensuring reliable trans-shipment hubs from Murmansk outward, and building robust rescue and response capabilities would turn the Arctic’s volatile weather from a crippling hazard into a manageable variable. The fourth is safer logistics. Replacing dark fleet tonnage with transparent, classed, and adequately insured ships is unlikely under current sanctions, but any easing or targeted carve-outs could logically be traded for higher operational and environmental standards.

Absent these shifts, the NSR will likely remain a niche corridor – reliable enough for Russia’s exports to a handful of partners – but not predictable or de-risked enough to attract the world’s container giants. In the end, the Route looks less like a global artery in waiting than a bespoke lane kept open by improvisation and political will. Russia has shown it can move volumes east without Western scaffolding. Still, the price is exposure: to China’s cautious leverage, to legal and governance ambiguity, to safety and insurance risk, and to a climate that can widen or snap shut the seasonal window with little warning. What emerges is resilience under constraint, capability sustained by workarounds rather than durable rules and partners. If geopolitics softens, the Arctic Council reactivates in full, and industrial bets from Zvezda to new icebreakers mature, the arc could still bend toward normalisation. Until then, this remains a sturdy yet narrow corridor; strategically vital to Moscow, serviceable for a few, and unlikely to host the time-sensitive traffic that defines a truly global route.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The End of an Exceptional History: Re-Thinking the EU-Russia Arctic Relationship

- Between Myth and Reality: Soviet Legacies in the Russian Arctic

- Neorealism’s Regional Blindspot: The Arctic and South China Sea

- Outsider Geopolitics: To Be, or Not to Be, in the Arctic

- Assessing China’s Strategy Towards Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine

- Post-Putin Russia: Five Potential Pathways