This article is part of a series on gender and sexuality in China. Read more here.

The year 2012 was known in the media as ‘The first year of China’s Feminist Activism’. I was part of a jury in the (2012) Fifth China Sex and Gender Event. We chose the year’s top ten activities, of which the tenth was “Feminists Are Active”. We covered a great number of actions that year: in February, one of the most vocal feminists in China who goes by the nickname Maizijia initiated a campaign to ‘occupy male bathrooms’ in Guangzhou; in April, Churan Zheng, a female undergraduate student of Sun Yat-sen University, wrote a public letter to the CEOs of the global 500 enterprises calling for a solution to gender discrimination in recruitment; in August, several women shaved their heads in Beijing to protest against the growing trend in Chinese universities where women must score higher entry marks then men and face unofficial but commonly acknowledged gender inequality; in November, some women and men uploaded their own nude photos and appealed to cyber citizens to eliminate violence against women and promote the legislation of Anti-domestic Violence Law; in December, in Guangzhou and five other cities, young women walked down the streets in wedding gowns covered in blood stains as ‘Injured Brides’, advocating people to protest against domestic violence.

I drafted the following announcement, which was then discussed and revised by the board of juries:

Feminists do not have enough channels to express their demands and opinions under the existing social system, so the younger generation of feminists has launched performance art activities in pubic spaces and on social media in order to advocate for women’s rights and to challenge China’s patriarchal culture. They have raised public concern regarding women’s rights, voicing concerns that have been repressed and despised, and challenging traditional gender roles through their performances. By shaving their heads, showing their naked bodies, and taking part in performances that shed light on the female body and women’s rights, they have subverted the traditional gender norms in China.

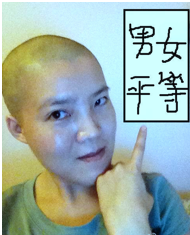

Although I work in an academic institute, I am not just an observer and researcher, I am also an activist. For example, I took part in the performance art of shaved heads in August 2012 with no hesitation. However I felt a bit shy to go to a hairdresser, so I ordered barber tools online and asked a colleague to shave my head for me at home. A photograph of my bald head was printed in postcards made by Chinese feminist activists. To this day, many of my friends still remember the time that I shaved my head, and challenge me saying that that act seemed to have very little connection to do with what we [feminists] were advocating for. While I have some regrets about this action, there remains a positive part – that also answers my friends’ challenge: it was a performative art that broke with gender stereotypes.

Yaya Chen, the author of this article, in 2012. The text reads ‘Gender equality’

For the ‘Injured Brides’ sub-performance in Shanghai in December 2012, I was one of the main planners. I recommended that the event take place to first at the Women’s Federation of Shanghai, and then at the Bund. This choice was a symbolic one: the former is an official organisation to protect women’s rights and the latter is a major landmark of Shanghai[1], both were meaningful for the project. When we arrived at the Bund, the area was large and exposed so even though the square was crowded (providing for a large ‘audience’), it was terribly cold and windy. After a short while, security guards walked up to us and told us to put down our signs. Even though they didn’t arrest us or force us to leave, for our own safety we soon left.

As a result of a photograph of me and others taken during the performance was posted online, I got a lot of pressure from people at work. I received several phone calls from an official who told me to delete this image because they had been contacted by the Women’s Federation of Shanghai[2]; the organisation possibly felt embarrassed by this, which is not the reaction I had expected. I thought they would have been pleased, since the movement was aligned with their concern for women’s rights – wouldn’t this be a positive thing? For this reason, I contacted the Women’s Federation of Shanghai via their official Sina Weibo[3] account. In the end, I had to delete these pictures from my own online account. Since all media outlets are policed to the same political standard, our feminist performance never made it to the printed press, and it looked as if we had only been doing this for our own entertainment.

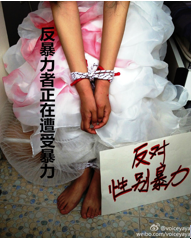

A performance of ‘Injured Brides’ against domestic violence, Yaya Chen (with short hair) and her feminist activism friend at the Bund, Shanghai, December 2012. The text reads: right side is ‘Love isn’t the beginning of violence’ (right), and ‘Violence is around you and me, are you still keeping silent about it?’ (rights)

A performance of ‘Injured Brides’ against domestic violence, Yaya Chen (with short hair) and her feminist activism friend at the Bund, Shanghai, December 2012. The text reads: right side is ‘Love isn’t the beginning of violence’ (right), and ‘Violence is around you and me, are you still keeping silent about it?’ (rights)

It is no surprise that women’s rights and related activities are monopolised by the official organisation, the All-China Women’s Federation (ACWF). Acting under the government of the People’s Republic of China, the ACWF and it’s branches have not only taken over some of the work on women’s rights, but on a different level it has also become a tool that exerts power on women and their organisation through the normal operation of state power. While the ACWF theoretically seeks a good balance between the responsibilities of feminist activism and representation of the state’s position, they tend to incline towards the latter duty, because they are civil servants whose political stance and funding come from the government.

With the central government’s backing, the ACWF considers that it has a stronghold on feminist activism; hence it does not welcome the performances of grassroots feminist activists. These not only bring no benefit to the ACWF, but on the contrary they even create some troubles for them. However, with the development of information technology and social organisation, the main force of the feminist movement seems to have returned to the people, and ACWF has been gradually forgotten. Somehow, grassroots feminists have developed a stronger social influence than the ACWF. In March 2015, five feminists were detained for 36 days for trying to advocate against harassment on International Women’s Day. They all came from non-governmental organisations, including Tingting Li (Maizijia) and Churan Zheng whom I mentioned above, and Man Wang, Tingting Wei and Rongrong Wu. They are important planners and participants in a lot of China’s feminist activist movements.

The famous political cartoonist Bajincao made this poster to support ‘Free the Five’ International Movement.

The famous political cartoonist Bajincao made this poster to support ‘Free the Five’ International Movement.

In 2006, I built a website with friends for publishing feminist news. We then thought about launching some other forms of activities. One of my partners had researched and proposed a kind of radical action in public bathrooms that was very similar to the feminist activists’ street performance ‘occupy male’s bathrooms’ but we never got a chance to carry it out. After 2012, I gradually reduced my involvement in feminist activist actions, because for a person like me who doesn’t like the:e ordinary social activities taking part in radical performances in the streets was too challenging.

In 2006, a young girl who was studying overseas interviewed me about women’s rights at a conference in Beijing. She asked me where I thought the ‘hope of Chinese feminism’ was. I told her that it was in the non-governmental groups, like our grassroots website. At that time, I had a negative attitude towards the ACWF, I thought they were hopeless and had no future. But now, the NGOs are in a similar situation. For example, for financial and personal reasons, our website can only provide basic functions like being a platform for women’s rights news and information, and a forum for feminists. There is nothing more that we that can do.

Even though I am less and less involved in these activities, I still follow the news about feminist activism in China. They are always doing things; not only have they focused on performances and demonstrationsbut they have additionally launched a national speaking tour, organised workshops on different topics, recruited and trained new members. Some of their activities are based on previously effective actions for example academic papers or conferences, and some of them are new ‘battlefield’ actions, such as working against (female child) sex abuse, supporting the strike of female cleaners, advocating anti-harassment laws on university campuses, and so on. The ranks of activists are growing larger: almost every city has prominent feminist figures who take part in activism, even in small and medium cities.

Wei Wei, the author of “Street, Behaviour, Art: Advocating Gender Rights and the Innovation of a Social Movement Repertoire”[4], interviewed as many participants as he could for this paper. He described a common character of these feminist performances that cannot be ignored: walking in the streets conveying gender equality is a soft but creative way to spread the message. The impact of street art has been positive. For example, after the performance of ‘Occupying Men’s Toilets’, the government of Guangzhou introduced a new set of policies: ‘Implementing Opinions on Improving the Proportion of Female Public Toilets’[5]. Shortly after that, Shenzhen, Beijing and other cities followed suit. Some other advocacy activities have also seen a political response. For example, in 2013, the Provisions of Admission of Entrance Examination of Institutions of Higher Education gave clearer guidance and prohibition against gender discrimination.

The success of these activities is also due to the creativity of the performances. It is also important that the selected actions do not enter into conflict with national policies, as this ensures that they are acceptable to the government. Finally, people must be able to see the impact of these activities in the short term. The art of advocacy is broad: it not only works through language, by appealing to public opinions through the media or by pressuring the government to make reforms, it also relies on actions., such as applying for information disclosure, running petitions and lobbying for women’s rights. The repetition of these actions means that the activists have been taken seriously.

Wei Wei also said that street performance, in comparison to direct confrontation, has its own advantage: it requires less social and economic capital, and reduces legal and political risks. But after the ‘five feminists’ incident, his positive attitude can be questiones, as their performance didn’t get a green light from the government. It has been a very heavy blow for feminist activism, and the relevant NGOs have now been unable to continue their work, their staff has had to find another way out.

Nonetheless, the ‘five feminists’ incident has not marked an end, but a new start for protest. After this year’s International Women’s Day, my friends and I wore the same wedding gowns we wore in 2012 for another performance in the honour of the five feminists called ‘Injured Brides are Imprisoned’. The purpose was to appeal for an end of violence against feminists. The photos of this new performance were banned online, but they were not deleted. To accompany the images, we wrote the following: “They are injured brides, working against gender-based violence and appealing for gender equality. Now they are imprisoned, enduring violence for every woman who wants to be free from violence, losing freedom for all women to gain freedom. It is time to do something for them: release the five feminists, stop the violence against feminists.

The text reads, “Against gender violence” (red) and “Opposition to violence is being subjected to violence” (black).

Now, the new generation of Feminist Activism has lost its voice in cyberspace, their groups have been forcibly disbanded, and members have been forced to leave to try and find other jobs, but this is not the end of the whole story. The kindling of feminism and (performance) actions is strong and tough, just waiting for the next wave.

Weeds will be more vigorous during spring, having survived the winter, and that spring is coming soon. The grass cannot be burned out by a prairie fire but grows again with the spring breeze. This is the wish for Chinese Feminist activism.

Notes

[1] The Bund has been the most emblematic area of Shanghai for centuries. It refers to the waterfront area which hosts many historical buildings, formerly governmental and since the 1970s increasingly financial. Between 2008 and 2010, the Bund was completely reconfigured and updated to best accommodate tourism.

[2] The Women’s Federation of Shanghai is a branch of the All-China Women’s Federation, which is the official leader of the women’s movement in China. Their website can be found here http://www.womenofchina.cn/about.htm

[3] China’s most popular online social media

[4] Wei Wei (2014) “Street, Behavior, Art: Advocating Gender Rights and the Innovation of a Social Movement Repertoire”, Chinese Journal of Sociology, Volume 34 (2), 94-117

[5] In the past few years, a major topic in feminist activism across China has been the increase of female public toilets. Proposals for official reforms were presented throughout the country by political representatives in the National People’s Congress and in the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference. They argue that an equal proportion of male and female public toilets does not seem to match the actual needs, since women effectively wait in line for a much longer time.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Introducing Feminism in International Relations Theory

- Opinion – How Polish Women Fight Their Right-Wing Government

- Opinion – The Chinese ‘New Left’ as Statist Apologists

- The Fight Continues: New Access to Abortion Services in Ireland

- Opinion – The Gendered Consequences of Coronavirus

- Opinion – Coming in from the Soviet Cold: Feminist Politics in Kazakhstan