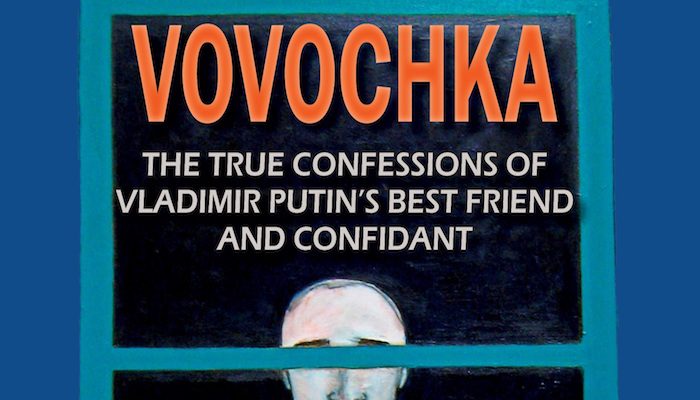

I recently sat down with Alexander J. Motyl to speak about his new book, Vovochka: The True Confessions of Vladimir Putin’s Best Friend and Confidant, as well as politics, popular culture, and the subject of this satirical romp through the end of Communism and the rise of the ‘new Russia’, Vladimir Putin.

Alexander J. Motyl is a writer, painter, and professor. Nominated for the Pushcart Prize in 2008 and 2013, he is the author of eight novels, Whiskey Priest, Who Killed Andrei Warhol, Flippancy, The Jew Who Was Ukrainian, My Orchidia, Sweet Snow, Fall River, and Vovochka, and of a forthcoming collection of poetry, Vanishing Points. He studied painting with Leon Goldin in Columbia University. Motyl’s artwork has been shown in solo and group shows in New York City, Philadelphia, and Toronto and is part of the permanent collection of the Ukrainian Museum in New York and the Ukrainian Cultural Centre in Winnipeg. His paintings and drawings are on display on the Internet gallery, Artsicle. As professor of political science, he teaches at Rutgers University-Newark and is the author of six academic books, numerous articles, and a blog ‘Ukraine’s Orange Blues’ at the online journal World Affairs.

The book’s description reads as follows:

Welcome to the Kremlin’s phantasmagoric world, where a heady mixture of Orthodoxy, socialism, imperialism, racism, sexism, homophobia, and Mother Russia worship defines and distorts reality. Vovochka is the fictional story of ‘Vovochka Putin’ and his intimate friend—a KGB agent with the same nickname. The two Vovochkas recruit informers in Berlin’s gay bars, spy on East German dissidents, survive the trauma of the Soviet Union’s collapse, fight American, Ukrainian, Jewish, and Estonian ‘fascists,’ and plot to restore Russia’s power and glory. As their mindset assumes increasingly bizarre forms, ‘Vovochka Putin’ experiences bouts of self-doubt that culminate in a weeklong cure in North Korea. A savagely satirical novel, Vovochka is also a terrifyingly plausible account of a Russian president’s evolution from a minor KGB agent in East Germany to the self-styled Savior and warmongering leader of a paranoid state.

In his review in the Spectator entitled ‘Russia’s Macho Leader Exposed’, Michael Johnson noted:

This book is long overdue — a sendup of Russian President Vladimir Putin, the macho horseman and judo master so often photographed with rippling pecs. The reality, says this comic novel, is quite the opposite…. Motyl pulls off a fine-tuned parody by using hackneyed Soviet language and blinkered thinking to recount historic and possible future events. The results are hilarious and often revealing of how the old Soviet mindset lives on…. Motyl’s story succeeds on two levels: it overlays actual events with a slightly skewed fictional story, and it exploits the bombast of Russian officialdom by pretending to take it seriously. The result is a parody in the great tradition of free expression.

Based on my own interest in how Putin in being portrayed in American and British popular culture, I asked a series of questions about the novel, beginning with why Motyl, a well-known critic of the Putin regime and particularly its position on Ukraine, decided to employ popular culture rather than the academician’s normal tools to go after VVP.

Saunders: You recently published a satirical novel entitled Vovochka: The True Confessions of Vladimir Putin’s Best Friend and Confidant (Anaphora Literary Press, 2015). While your previous novels have been overtly political, this one takes on one of the world’s most known political actors, the president of the Russian Federation. Why did you feel compelled to write this book now?

Motyl: I had the idea for the book sometime in the summer of 2014, as war was raging in eastern Ukraine and Putin was denying all responsibility for it. I had been criticizing Putin for his authoritarian ‘fascistoid’ tendencies in my academic and policy writings since he came to power in 1998-99; in late 2013 and early 2014, I increasingly claimed that his foreign policy was incompetent and, in fact, stupid, having resulted in the permanent loss of Ukraine and the reactivation of NATO. At the same time, Putin’s hyper-masculine blustering—his incessant Tarzan-like chest-beating—seemed to be on the rise, as he pranced and preened before his adoring Russian audience. As the man came to parody himself, it occurred to me that a parody of the man was necessary, for both artistic and political reasons. I first painted two parodies of him (one of which serves as the cover for the novel); a written parody seemed like the obvious next step.

RAS: In the book, you are at pains to state this is a work of fiction and not necessarily based on the ‘real’ Putin; however, the narrative assiduously follows the life and times of VVP. What is ‘true’ in these ‘true confessions’ and what is fiction, and on more philosophical level, is the line blurring between the two in a world where the popular and political increasingly collide and collude?

AJM: Putin shamelessly denies obvious facts and just as shamelessly proclaims the veracity of obvious falsehoods. My foreword, which emphatically denies that the fictional Vovochka has anything to do with the real Putin, was written in the spirit of Putin’s rhetoric and is, thus, a parody of that rhetoric—and, of course, of itself. The ‘true confessions’ format will be familiar to students of American pop culture. They’re rarely confessions and they’re almost never fully true. So, too, with Vovochka. It draws on and follows certain facts, but is otherwise an invention. And yet, this invention, which is an intentional distortion of the truth, is arguably a ‘truer’ depiction of today’s Russia and the people who misrule it than any non-fictional account. Putin’s Russia, like Putin himself, has become a parody of itself, and the best way to capture that ‘essential’ feature may be the parody genre. Your final point, about the blurring of lines between the popular and the political, is very important. Images and representations have become central to pop culture and politics, both in Russia and the West. Putin knows that, and therefore tries very hard to construct a cult of the macho personality that depicts him as Russia’s Super-Dude. He wasn’t the first to elevate his masculinity to the level of politics, of course: Mussolini was one of his predecessors.

RAS: What do you hope the reader will take away from the experience of reading a farcical treatment of Putin’s adventures which include pilfering underwear from political dissidents, dressing in drag, trolling gay bars for ‘converts’ to the cause of socialism, and seemingly endless massages from his ‘confidant’ and covert political advisor Vovochka?

AJM: My point, obviously, is to subvert Vovochka’s self-representation as Russia’s hyper-masculine, macho, gay-bashing Super-Dude. What better way to undermine this ridiculous pose than to hint at completely opposite sexual proclivities? As you know, some Putin-watchers have suggested that his macho pose may be a cover for deep-seated insecurities. My invented Vovochka may therefore be a more accurate depiction of the real Putin—accidentally and unintentionally, of course!—than the true-to-life image of Putin found in biographies.

RAS: Your book requires substantive familiarity with the geopolitics of the former Soviet Union. When writing the novel, were you worried that the casual reader would be turned off by in-depth discussions of the collapse of one-party rule in East Germany, Georgian regionalism, Ukraine’s Orange Revolution, and Aleksandr Dugin’s rather esoteric ideology of Eurasianism?

AJM: I should be so lucky as to have thousands of confused casual readers! My guess is that the vast majority of my readers have some background knowledge of the Soviet Union, Russia, and Ukraine. That fact aside, I think one can read and appreciate the book as a straightforward satirical depiction of a bizarre man’s even more bizarre political evolution. After all, all novels function on at least two levels: that of the simple story and that of the deeper meanings that accompany the simple story.

RAS: Given the events surrounding the 2014 film The Interview which satirically depicted Kim Jong-un and prompted a massive data breach at Sony costing untold millions alongside the release of sensitive information that embarrassed company execs, do you have any concerns that your work of fiction might compromise your professional standing or harm you in other ways (particularly given the proven track-record of pro-Kremlin hackers in ‘defending’ the image of Russia)?

AJM: Vovochka is my eighth novel, and I’ve long since stopped worrying—if, indeed, I ever worried—about the academic world’s reception of my literary efforts. Besides, novels are novels, academic monographs are academic monographs, and paintings are paintings. Despite our general infatuation with interdisciplinarity, I can think of no way of producing syntheses of these three genres. They’re different, and my hope is that people will judge the merits of my novels on literary grounds, my monographs on academic grounds, and my art on aesthetic grounds. As to Putin’s apologists and pro-Kremlin hackers, I trust the book will drive them crazy.

RAS: In the book, you take a few of your fellow academics to task for their slavish support of the Putin regime. While he is not mentioned by name, Princeton professor of Russian history Stephen F. Cohen, is referenced quite explicitly once or twice. Numerous other public figures involved in the affairs of state are mentioned as well, not always in glowing terms. Could you comment on the use of popular culture (in this case, your novel) as a growing means of debating larger issues in international relations?

AJM: There’s also a disparaging reference to me! As to your question, literature—or more generally culture—enables one to address questions and provide answers that would be impossible in non-fiction. Academic studies of international relations are bound by the rules of logic and evidence. You’re not supposed to contradict yourself and you can’t make up facts. Popular culture, in contrast, can violate all these rules. It can embrace contradiction—indeed, the narrator in Vovochka contradicts himself on several occasions—and it can invent facts. In that sense, popular culture is like politics. Much to the annoyance of academics, politicians routinely contradict themselves—and often pay no price for doing so—and they stretch, if not quite invent, facts—again, without paying any substantive price for doing so. In both endeavours, images and representations matter more than logic and facts. That’s OK for culture; it may be less so for politics.

RAS Any interest in having the book translated into other languages? Polish, Ukrainian, German? And in a related question, how do you think the book might be interpreted outside of the US/UK market? Any feedback from Russia as of yet?

AJM: A friend with contacts with a Kharkiv-based publisher will try to persuade them to translate Vovochka into both Russian and Ukrainian. My guess is that readers will fall into one of two camps: they’ll either love or hate the satire. The former are likely to be Putin skeptics; the latter are likely to be Putinophiles. Putin lovers are a decidedly serious bunch who take umbrage at any suggestion that their man is a Mel-Brooksian character. Indeed, who better to play Vovochka in a film than Mel Brooks?

RAS: Putin has become a major focus of your work as of late, including numerous articles, blog posts, three paintings, and now the novel. What next for you and VVP?

AJM: Putin has become a predictable bore. Unfortunately, he’s also one of the most dangerous world leaders who could, through a combination of hyper-masculinity, insecurity, desperation, and foreign policy stupidity, destabilize substantial chunks of the world. Ukraine stopped him, but the eastern Donbas and the Crimea have become, thanks to Putin, unlivable hellholes. Now it’s Syria’s and Turkey’s turn. Estonia and Kazakhstan could be next. Putin bears the responsibility for the deaths of hundreds of Russians in the apartment bombings of 1999, tens of thousands of Chechens, scores of Georgians, 200 passengers of MH17, some 8,000 Ukrainians, and now hundreds, thus far, Syrians. His appetite for death may be limitless, and the longer he continues plying his evil trade, the unfunnier he’ll get. Of course, it’s exactly then that parody and satire will, as Mel Brooks knew, be imperative. But not for me. He’s great material, but I’m waiting for the day that he leaves what is euphemistically referred to as the historical stage and becomes a bad memory.

My sincere thanks go out to Dr. Motyl for his generosity in sitting for this interview.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – The West’s Mental Lockdown over Putin’s Invasion of Ukraine

- Opinion – On 9 May Putin’s Russia Will Glorify War and Stalin

- Putin’s Russia: Violence, Power and Another 12 Years

- Post-Putin Russia: Five Potential Pathways

- Opinion – A Psychological Perspective on Putin’s War with Ukraine

- Vladimir Putin’s Imperialism and Military Goals Against Ukraine