Africa as a continent has continued to face changes in conflicts which have led to the insecurity within its borders. The insecurity has been seen largely in form of coups, genocides, ethnic cleansing, xenophobia, and lately rampant of all is electoral insecurity. This very latter form seems to be institutionalized through democracy. The other cause of insecurity that is sporadic but also dreadful as electoral conflicts, is terrorism. Many factors can be attributed to the changing nature of African conflicts; the collapse of communism and the creation of a unipolar system under the United States administration.

In essence, this means that the political system propagated for practice is democracy thus the normal problems associated with it seem enormous in the local African politics where systems may not want to embrace the democratic culture. This has resulted in so many electoral related conflicts which have more than a single country effect.

Africa Conflicts from old Legacies to New Realities

Perlez (1992) is keen on pointing legacies of Cold War to Africa thus, in many African Countries, an onerous legacy of the cold war is centralized government control, particularly over economic matters, many experts say. In an address in Washington last October, Prof. George B. N. Ayittey, said that while there was a deep-seated fascination with socialism across the continent, the basic problem of Africa is statism. Whatever the ideological professions of African governments, most – even so-called capitalist states – have been characterized by heavy state interventionism, he said and continues, the solution for Africa was a situation in which no individual or group, regardless of religion, race or ideological predilections, can capture the state.

Once avidly wooed by Washington and Moscow with large amounts of economic aid and modern armaments, the impoverished nations of Africa now find themselves desperate for friends. In the late 1980s and early 1990s (Perlez, 1992), superpower rivalry has been replaced by international indifference. Chege (1991) concurs that with the end of the Cold War, Africa has lost whatever political lustre it may have once had,” Michael Chege, wrote in the journal Foreign Affairs. There are no compelling geopolitical, strategic or economic reasons “to catapult it to the top of the global economic agenda,” he said. “Africans must now take the initiative.” He continues to note that the abandonment is vividly evident here in the Horn of Africa. Ethiopia and Somalia, which were at the center of the tussle for influence on the African continent in the 1970’s, now lie devastated, orphans of the post-cold-war era. The end of the Cold War and of apartheid has undermined the logic that once drove America’s alliances of expediency on the continent, which were so inimical to expanding civil liberties in Africa. The West should develop a selective foreign policy, favouring states showing pro-market and pro-democracy traits, and showing equal-opportunity hostility to remaining despots.

Noting that American leaders for generations have emphasized the promotion of democracy abroad as a key element of America’s international role, President Woodrow Wilson proclaimed that America was fighting World War I to make the world safe for democracy. When policymakers decide they are going to try to promote democracy in another Country, they typically reach for various tools. The officials may use diplomatic measures, as either carrots or sticks: criticizing a government that is backtracking from democracy, praising a pro-democracy leader, granting or withdrawing high-level diplomatic contacts in response to positive or negative developments, and so on (Carothers, 2011).

As in Chege (1991), the West may have changed, the policies of the United States and its European allies toward Africa are still not the supportive pillars of stable market-driven democracies they could be. But much also depends on Africa itself. The pace of their own reform, how quickly they can devise new development policies and institutions more consonant with the march of history toward economic and political liberalism, will help determine the full impact of external support for change. Chege may not be right because regionalism in Africa is being supported by the same alliances.

On democracy, Carothers (2011) notes that in extreme circumstances, the United States may even employ military means to promote democracy, intervening to overthrow a dictatorship and install or re-install an elected government although U.S. military interventions that politicians justify on democratic grounds are usually motivated by other interests as well. The most common and often most significant tool for promoting democracy is democracy aid: aid specifically designed to foster a democratic opening in a nondemocratic Country or to further a democratic transition in a country that has experienced a democratic opening.

To observe, donors typically direct such aid at one or more institutions or political processes from what has become a relatively setlist: elections, political parties, constitutions, judiciaries, police, legislatures, local government, militaries, nongovernmental civic advocacy groups, civic education organizations, trade unions, media organizations. Prior to the 1980s, the United States did not pursue democracy aid on a wide basis. In the past two decades, such aid has mushroomed, as part of the increased role of democracy promotion in American foreign policy. According to Carother’s, it started slowly in the 1980s then expanded sharply after 1989 with the quickening of the global democratic trend. By the mid-1990s, U.S. annual spending on such programs reached approximately $600 million and now exceeds $700 million. A host of U.S. government agencies are involved; in 1998 the United States carried out democracy programs in more than 100 Countries, including most Countries in Eastern Europe, the former Soviet Union, sub-Saharan Africa, and Latin America, as well as many in Asia and the Middle East. The current wave of democracy aid is by no means the first for the United States.

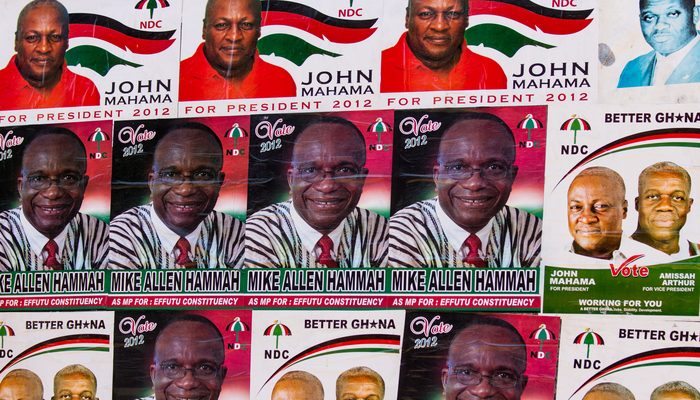

A moral question worth asking is whether democracy is really the antidote to peace in most problems in Africa. This may cast questions on whether the institutions of democracy are peaceful in themselves. As the American policy of democracy increases through activities like elections, so does the level of conflicts also rise. The paradox resulting from the parallelism in which the two rhyme is interesting. Almost explicit to observe in the African content is the connection of democracy wars. These are seen by its failure and now leading to many discontented citizenry as Juma and Oluoch (2013) notes. It thus leads to asking on how democracy through elections will be conducted in order to refocus regional security. In the post-cold war era, a continental shift in terms of the independent era conflicts of coups is really being felt in Africa.

Into Conflicts and Regional Security

In Political Insights into African Democracy (2013), Juma and Oluoch highlight the fact that, since the end of the conflicts of coups and bush wars. Two near waves of conflicts are engulfing Africa, Conflicts from elections and Global Urban Uprisings (GUU). They continue to say … the year 2000 to date, almost ten elections have caused conflicts hence causing worries. Why? Because it antagonizes even those perceived peaceful states and upcoming economic giants.

Human Rights Watch (2004) notes that during the 2003 Federal and States elections in Nigeria, at least 100 people were killed and many more were injured. Approximately 600 people were reported killed in the recent election violence in Kenya, following disputes over the results of the December 2007 presidential elections.

Similarly, (Atuobi, 2008) records that during the August 2007 run-off elections in Sierra Leone, violence erupted following a clash between the supporters of the ruling Sierra Leone People’s Party (SLPP) and the opposition All People’s Congress (ACP). Violent attacks were also reported against the supporters of the SLPP when the ACP leader was sworn in as the new Presidents. The persistence of election-related insecurities manifests as if they are only found in the African continent yet they are global mostly among Developing Countries.

In Ebert (2001), election-related violence is defined as political violence aimed at the electoral process. It is geared towards winning the political competition of power through violence, subverting the ends of the electoral and political process. The erupting election violence or election-related violence is understood as a violent action intended towards some people, property or the electoral process, whose main purpose supposedly has an end goal to influence the electoral process before, during or after elections. Election violence can therefore aptly be deduced to take two perspectives – cultural and structural. The viewpoint by Ebert seems to ignore other forms arising from election violence; systemic and institutional. On the other hand, he deals with a normally formed opinion on African violence.

The second perception presupposes as Ebert points out the existence of a political culture of thuggery that generally predisposes actors to engage in violence and intimidation during political contests, while the structural explanation suggests that society and politics are organized in a manner that generates conflict. These two perspectives are reinforced by ethnic rivalries and mobilization in politics in most African Countries that have been volatile during elections.

There are several factors responsible for election-related violence on the continent, among them structural weakness in election management, and especially the election management bodies; the nature of the electoral system (that is, the winner-takes-all); abuse of incumbency (access to state resources, manipulation of electoral rules); identity politics; heavy-handedness of the security forces during elections; and deficiencies in election observation and reporting (Atuobi 2008). The argument built above exposes the nexus between electoral management and security since the characteristics of Atuobi’s bedrock suggestions are elements that would normally drive disappointed masses to violence. This works so negatively to those who belong to the losing side. Although, even the winning side easily becomes defensive, a situation that builds confrontation.

In other related literature, Ogwora (2015) is assertive that, from Cape Town to Cairo, or from Nairobi to Abidjan, there is a simmering political crisis in every country. The honest observation and assessment of the political atmosphere and progression of African countries is worrying. Today, there is no tension in a particular African country, but this does not mean that issues of social, economic and political turbulence could not emerge. Perennial political instability has existed in countries like Somalia, DRC Congo, Sudan and others.

In my view, whereas Ogwora observes correctly the existence of security threats, he also wants to mean the absence of the same which is a contradiction. In fact, from Cape to Cairo and likewise Nairobi to Abidjan comprise electoral tensions namely Zimbabwe, Kenya, Uganda, Burundi, Rwanda, and Congo the period in years notwithstanding. Ogwora, however, rightly point as Atuobi among the many factors for election-related violence and link them to, two paramount concepts that he thinks can be used to free Africa from the embedded crisis. These conceptions he believes are constitutionalism and democracy. Again from him, mention of democracy is talking about the election since it is a tool for measuring the practicability and existence of democracy.

Similarly, observations by Atuobi indicate that in some Countries including Rwanda, Burundi and Côte d’Ivoire shows many widespread conflicts were preceded by disputes over the electoral process and election results, among other factors in aggregate. In most post-conflict states worldwide, violence and disputes arising from elections and over election results have the ability to derail peace processes and ignite after effects both to originating Country and others in the neighbourhood.

In 1992, following disputes over the election results in Angola, the National Union for the Total Liberation of Angola -(UNITA) returned to war, which lasted almost a decade.

Empiricisms and Normativism of Electoral Security

Security impasse in states creates highly precarious conditions for eco-socio-political developments. Through observation; conflicts, violence, and wars synonymize security hence approach at handling their interplay whether in electoral violence or ethnic altercations are moves to secure states and by extension, those in closely connected regions. According to political theorists (Steffensmeir, Brady, and Collier, 2008), subjects of political inquiry involve the application of political methodology through techniques for clarifying the theoretical definition and meanings of concepts such as revolution. It also provides descriptive indicators for comparing the scope of revolutionary change, presenting an array of methods for making causal inferences that provide insights into the causes and consequences of revolutions. This buoys the essentialism of observation in the study of the phenomenon.

Understanding of electoral management dynamics and East Africa Regional Security (EARS) architecture links insecurity to conflicts. This studiously undertaken requires unravelling of concepts. The study finds nature of conflicts fundamental to clarity in meanings. Gerring (2001) suggests, we might identify and define a concept by adopting a definition others have used; considering what explains the concept or what it explains, exploring its intellectual history, or grouping the “specific definitional attributes” that are available. Shawn Grimsley asserts that inquiry into political issues hangs on a political theory which embodies ideas and values concerning concepts of state, power, individuals, groups, and relationships between them. Theories attempt to describe, explain, and predict scenarios as elections and security for state decisions. In this empirical political theory explains “what is” while normative “what ought” through observation of phenomenon (Govier, 2005).

In summarizing the nature of conflicts in Africa, the research finds it imperative that clinical identification and analogy of characteristics of conflicts is primacy to regional security architecture. Through observations, conflicts characteristics are;

• Multifaceted,

• Intertwined,

• Diverse as any known society,

• Their causes or sources reflect their types,

• Reminiscence of natural sociological tendencies,

• Endemic in countries-in-transition,

• Difficult to know their end except for the relativity of conditions described as peace,

• Complex thus management should reflect this, and

• Contagious and possess geographic proximity cause and effect syndrome.

The characteristics above in relation to EMBs describe the kind of dynamism that EM violence leaks to EARS.

References

Atuobi, Samuel Mondays (2011), Election-Related Violence in Africa; www.ace.org

Carothers, Thomas (2011), Aiding Democracy Abroad: The Learning Curve, The Carnegie Endowment For International Peace, Washington, DC.

Chege, Michael (1991), Remembering Africa; America and the World Issue 1991, Council on Foreign Relations.

Ebert, Fredrick Stiftung and Centre for Conflict Research (2001), Political and Election Violence in East Africa; Working Papers on Conflict Management No. 2, p.1.

Gerring, John (2001). Social Science Methodology: A Critical Framework. Cambridge University Press.

Govier, T. (2005). A Practical Study of Argument. 6th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Human Rights Watch (2004), Nigeria’s 2003 Elections: The Unacknowledged Violence Summary, http://hrw.org/reports/2004/nigeria, 9th January 2008.

Juma, Thomas Otieno and Ken Oluoch (2012), Political Insights into African Democracy and Elections; Lambert Academic Publishing, Germany.

Ogwora, Eric Thomas (2015), Constitutionalism and Constructive Democracy: A Solution to Political Crisis in Africa and The Impact of The American Democratic Model, Online Journal Modelling the New Europe. Dec2015, Issue 17, p93-112. 20p.

Perlez, Jane (1992), After The Cold War: Views From Africa; Stranded By Superpowers, Africa Seeks An Identity, New York Times May 17th 1992.

Steffensmeier, J.M.B., Brady, H.E., and Collier, David (2008). Political Science Methodology: The Oxford Handbook of Political Methodology. Oxford University Press.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The Changing Geopolitical Context of US Support for Human Rights and Democracy Promotion

- Science, Technology and Security in the Middle East

- The Changing Security Dimension of China’s Relations with Xinjiang

- Opinion – The Path Beyond Trump in US Human Rights Policies

- Opinion – Nigeria’s Stagnation on Anti-Corruption Links with Growing Insecurity

- African Democratisation and the One China Policy