In the hope of deterring undocumented migration, key U.S. immigration officials signed off on the April 2018 ‘zero tolerance’ policy to criminalize unauthorized entry. The resulting forced separation of parents/guardians and children prompted accusations of racial violence by a number of human rights organizations, journalists, and concerned U.S. citizens. I argue that one cannot understand how migration deterrence operates without also examining the role of gender violence. I understand gender violence to generally comprise acts and practices, such as interpersonal violence, sexual assault, forced pregnancy, or gang conscription and rituals, that target a person or group in order to punish transgressions of expected gendered behavior; gender violence is also an assertion of masculinist power that disciplines men and women to behave in ways that reinforce gender hierarchy and power relationships.

My focus in the rest of the essay is on the two key lessons we learn by looking at the gendered violence of deterrence. First, I explore how the U.S., through cooperation with Mexico in deterring undocumented migration from Central America as well as drug trafficking, contributes to the very gender violence that prompts migrants to flee their countries. This bilateral relationship also empowers Mexican state officials and criminal networks to target migrants traveling through Mexico with gender violence. Thus, we see how deterrence measures both exacerbate and trap migrants in untenable situations of gender violence.

Second, I show that an examination of gender violence reveals the dynamics of the political responses to gender violence, including narratives about what counts as gender violence and who counts as victims of this violence (Nayak and Suchland, 2006; Nayak, 2015). I accordingly look at the U.S. governmental attempt to deter migrants from applying for asylum due to gender violence by denying that such violence is persecutory, and by signaling that the ‘real’ victims of gang violence are not migrants but rather U.S. citizens.

Regional Cooperative Deterrence

‘The Guatemalan border with Chiapas, Mexico, is now our southern border’, stated then-Department of Homeland Security official Alan Bersin in 2012. The context behind this statement is how the U.S.’s war on drugs in South America increasingly pushed drug production and the accompanying violence north to Mexico and Central America by the 1990s to early-to-mid 2000s. The U.S. has since focused a tremendous amount of attention on Mexico’s southern border, supporting Mexico’s ‘war on drugs’ and deterrence of Central American migrants through the Mérida Initiative (2007-present) and Programa Frontera Sur (Southern Border Plan) since 2014. The Mérida Initiative also includes resources for anti-drug actions in Central American countries, particularly in Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras. But attempts by Mexico and Central American countries to combat drug trafficking have escalated human rights violations by both governments and crime networks, particularly as governments also use these security measures to justify the repression of citizens. The U.S. and Mexico’s cooperative deterrence has only increased the militarized criminalization and profitability of drug trafficking and thus strengthened criminal networks in the region. Crucially, U.S. financial support to Mexico requires and perpetuates a conflation of undocumented migration and drug trafficking as one problem to be controlled through strict border control.

Migration deterrence demonstrates sovereign power, which is how the state constructs itself as sole authority to decide who belongs and who does not, who is worthy and who is not, who should live and who should die (Nayak, 2015). Attempts to showcase sovereign power through border control require both racial and gender violence. Feminist scholarship shows how the militarization of borders increases and necessitates violence, particularly against women, because it normalizes masculinized violence and the importance of domination to control people’s bodies. More specifically, border enforcement displaces poor border communities, particularly working class women, for the sake of gentrification and the accompanying illusion of safety; increases the number of armed officers interacting with local communities and migrants; enables border officials to sexually attack women with impunity; and empowers local officials in border towns to kill “undesirable” people.

Sayak Valencia points to the ironic ‘anything goes’ nature of borders, showing that despite and because of border enforcement, ‘control’ of what and who enters/exits countries requires an environment of chaotic violence (2018: 182). She argues that in the context of the ‘drug war’ in Mexico, the intensification of excessive, brutal, predatory violence against vulnerable bodies is purposeful (19-20). She contends that the Mexican state deals with the ‘increasingly demanding logic of capitalism’ and its contentious relationship with the U.S. through ‘necroempowerment’, which commodifies and profits off of violence and death (19). The Mexican government effectively legitimizes underground economies of drug and weapon trafficking as well as the use of death, kidnapping, and terrifying spectacles of violence because it seeks to ‘delimit [drug cartels]’ rather than eliminate them (52). Guided by the desire to benefit from organized crime’s financial power, the Mexican government asserts its own power through murderous, masculinist acts of ‘settling scores’ with cartels, rather than by protecting citizens (24, 55, 57).

U.S. actions have contributed to gender violence not only at its border but also within Central America and Mexico. First, U.S. support for anti-drug policies and border enforcement has increased gender violence within Central America precisely by, as discussed above, strengthening and militarizing the conflict between organized crime and governments in Central America. Thus, the gender violence that prompts Central American migration is not accidental or mysterious. Central American families are fleeing due to staggering levels of domestic violence, rape, femicide, and sexual violence at the hands of gangs[1], other organized criminal networks, or the governments, or with the tacit approval of governments. Lawyers and human rights advocates who have interviewed separated parents reveal that gang members in the migrants’ home countries had murdered or kidnapped family members, sexually assaulted them or relatives, threatened to murder or rape their children, and brutalized them with the ever-present threat of hypermasculinized payback for failing to obey gang codes. Gender violence is central to how gangs increase and maintain their power, an element of their strategy that government officials systematically overlook, or engage in themselves.

The current situation in Central American countries also finds its roots in the civil wars. With U.S. intervention intensifying the wars, a significant number of migrants fled to the U.S., where they often participated in gang networks as a method of protection and community. When the U.S. deported these undocumented gang members, they were then able to build their size, influence, and financial power in Central America and to create ties with regional drug cartels. Domestic violence and systematic misogyny are two of the legacies of the civil wars in Central America, as is the case in most post-conflict situations.

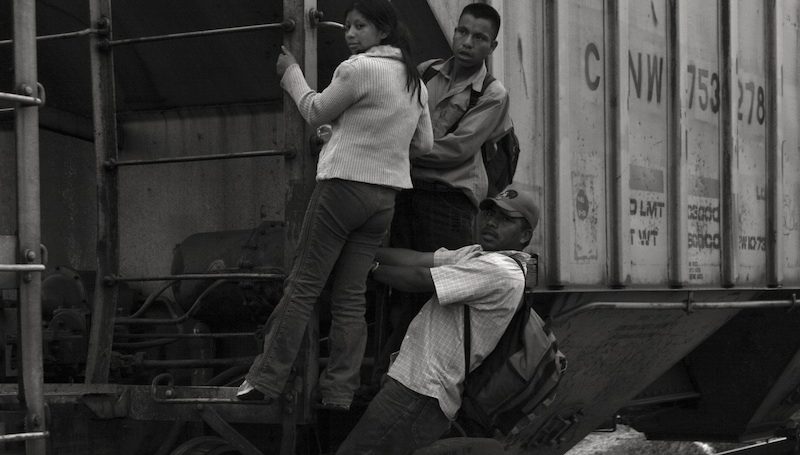

Second, anti-drug and migrant deterrence policies embolden criminal networks and Mexican state officials to target Central American migrants who are crossing into or moving through Mexico. For example, strengthened criminal networks inside Mexico raise fees for smuggling migrants and assault and murder migrants with impunity. As migrants end up on more remote and dangerous trails to avoid border enforcement measures or deportation, they are subject to robbery, extortion, gang conscription, forced sex work, and sexual assault by criminal networks, affiliates of Central American gangs, smugglers, and Mexican officials. The majority of women traveling on migrant routes through Mexico experience sexual assault, to the point that women and teenage girls get birth control injections known as the ‘anti-Mexico shot’ before their journeys.

Mexico also stepped up its deportations of Central American migrants at the behest of the Obama Administration in 2014. In recent years, Mexico deported twice as many Central American migrants as the U.S. did. Deportations send migrants back to the very violence they fled or to increased pressure to join gangs upon their return.

Human rights groups[2] in Mexico and the U.S. routinely critize Mexico for directly engaging in or openly allowing abuses/violence against migrants. Despite knowledge of these acts of violence throughout the region, the U.S. feigns a moral commitment to fighting drugs and undocumented migration as ‘a justification for an interventionist policy that perpetually endeavors to control the countries ‘punished’ by drug trafficking’ (Valencia, 2018: 173). Despite Trump’s bluster about building a wall that Mexico will finance, his administration has greenlighted continuation of funds to assist Mexico in deterring drug trafficking and migration alike. And so the reasons for migration will continue.

Gender Based Asylum

We need to look at not only the causes of gender violence but also responses to gender violence. The U.S. is reframing gender violence to delimit what counts as violence and who counts as a victim, specifically in the context of migrants applying for asylum. Under international and U.S. refugee law, one may be able to receive asylum if he or she can prove he or she fled persecution due to one of five grounds: race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership of a social group. Because gender is not one of the grounds of persecution in refugee law, asylum lawyers and advocates have worked to frame gender-based persecution (such as domestic violence, coercive female genital cutting, forced marriage, rape) as part of the social group category. An example of a domestic violence claim might be ‘persecution due to being a member of the group of married women in Guatemala who are unable to leave their relationships’. Social groups targeted by nonstate actors are considered persecuted groups because governmental institutions enable and reinforce such violence (Nayak, 2015).

Asylum claims by Central American and Mexican migrants in the U.S. are generally not successful. El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala, Mexico, and Haiti are the top 5 ‘asylum-sending’ countries to the U.S., but approximately 80-90 percent of asylum claims from Mexico and Haiti are denied, and approximately 80 percent of asylum claims by Central American migrants are denied, as compared to 50 to 60 percent for migrants in general. Ever since the U.S. started to outsource deportations to Mexico in 2014, asylum rates in Mexico for Central American migrants have risen slightly, but the overall number of asylum applicants remains very low given significant problems with Mexico’s asylum system.

Based on my analysis of data from the Center of Gender and Refugee Studies,[3] domestic violence and gang violence, two types of gender violence, are usually the most cited reasons Central American migrants leave their countries. It is no coincidence that Attorney General Jeff Sessions issued a new policy that domestic violence and gang violence are no longer grounds for asylum, making it even more difficult for these migrants to receive asylum. Sessions has been using the rarely invoked self-referral mechanism, which means intervention in pending or resolved asylum cases to issue a decision that may vacate previous decisions that shape asylum policy. He not only changed procedural options that now make it harder for asylum seekers to get due process, but he decided to interfere with one particular case on domestic violence, Matter of A-B-. A.B., a Salvadoran woman, fled to the U.S. after years of brutal violence at the hands of her husband and the refusal of the police to assist her.

After an immigration judge denied her asylum claim based on her credibility, the U.S. Board of Immigration Appeals (within the Department of Justice) reversed the denial and sent the case back to the same immigration court to conduct background checks necessary for the grant of asylum. But the immigration judge sent the case back to the Board. Months later, Sessions referred the pending case to himself. Instead of focusing on the credibility issue, he decided to look at the very basis of persecution, domestic violence, one that has been widely recognized as a legitimate claim in U.S. asylum law. In June 2018, Sessions changed asylum policy so that persecution due to domestic violence and gang violence could no longer be considered as grounds for receiving asylum.

Why did Sessions refer this particular case to himself? First, his decision illustrates his goal to reframe domestic violence as a private crime rather than as persecutory. He referenced the Matter of Pierre (1975), in which the U.S. Board of Immigration Appeals described domestic violence as personally rather than politically motivated. He thus revived legal reasoning that countless feminist legal scholars and asylum analysts[4] have debunked over the years. This decision, in effect, challenges fifteen years of work that established domestic violence is persecutory. He also used the same rationale invoked by Central American governments for failing to address domestic violence: it is a personal issue. Thus, the Trump Administration’s actions reinforce patriarchal framings of gender violence, which impact not only future asylum cases but also discourses about gender violence, given the importance of asylum cases in messaging how the the U.S. understands gender violence.

Second, framing domestic violence as a private crime committed by a nonstate actor allowed Sessions to name another nonstate actor: gangs. Sessions noted in his decision: ‘The mere fact that a country may have problems effectively policing certain crimes-such as domestic violence or gang violence–or that certain populations are more likely to be victims of crime, cannot itself establish an asylum claim’. As mentioned above, U.S. officials are well aware of the amount of gang violence in Central America as well as how gangs target migrants throughout Mexico. So Sessions mentioned gang violence in the domestic violence case precisely so that the U.S. stops looking at Central American migrants as victims of gang violence. As he noted in the decision, facing gang violence is difficult and unfortunate but not persecutory for Central American migrants. However, as we situate this asylum policy change in the Trump Administration’s immigration discourse, we see that the U.S. government does frame gang violence as persecutory for Americans, the putative real victims of gangs.

Trump signed an executive order to end the family separation policy on June 20, 2018. But on June 22nd, 2018, two days later at 9:43 a.m., he tweeted:

We must maintain a Strong Southern Border. We cannot allow our Country to be overrun by illegal immigrants as the Democrats tell their phony stories of sadness and grief, hoping it will help them in the elections. Obama and others had the same pictures, and did nothing about it.

Later that same day, he hosted families whose relatives were killed by undocumented immigrants. Trump announced: ‘These are the American citizens permanently separated from their loved ones…They are not separated for a day or two days. Permanently separated.’

This jab at the separated migrant families illustrates the Trump Administration’s contempt for these migrants. Central American migrants are not only discounted as victims, but they are also framed as perpetrators: they may be or become gang members. As Trump noted in his January 2018 State of the Union Address: ‘Many…gang members took advantage of glaring loopholes in our laws to enter the country as unaccompanied alien minors’. At an immigration roundtable at the Morrelly Homeland Security Center in May 2018, Trump repeated the claim that ‘[t]hey exploited the loopholes in our laws to enter the country as unaccompanied alien minors. They look so innocent. They’re not innocent’. In the U.S. immigration system, one does not need to be a gang member to be identified or accused as such. The NY Immigration Coalition and CUNY School of Law recently reported the merging of the policing of gangs and immigrants, resulting in false accusations of gang membership based on very flimsy criteria like the presence of a tattoo and subsequent deportation or family separation.

Only about .02 percent of all unaccompanied children apprehended at the U.S. border are suspected or confirmed to have gang ties. Journalist Jonathan Blitzer notes that ‘the president only talks about these gang members as savages and the victims as precious or beautiful people. [But] most of the victims tend to be either immigrants themselves or the children of immigrants’. Raising the issue of gangs in every discussion about immigration or borders not only racializes immigrants as perpetual threats but also strategically sidelines acknowledgment of gang-related gender violence against Central American civilians as persecutory.

Conclusions

Politicians and journalists alike have described the family separation crisis and its aftermath as ‘cruelty for cruelty’s sake’. However, this policy is very much part of the logic of migration deterrence. It is crucial to demystify and contextualize seemingly ‘unfortunate’ harm so as to analyze migration deterrence as a deliberate enterprise. There is increasing attention to the racial violence of deterrence, such as examinations of racial profiling, the dehumanizing rhetoric of migrant ‘infestations,’ and the echoes of U.S. historical practices of separating nonwhite families, such as indigenous Americans, slaves, and interned Japanese-Americans. However, racial and gender violence are undoubtedly intertwined, and we subsequently need a deeper interrogation of all facets of migration deterrence.

In addition to family separation policies, the U.S. also engages in several other tactics meant to deter migrants. For example, Jason De León’s (2015) book brilliantly and comprehensively examines how the U.S. deliberately funnels migrants into the treacherous and deadly terrain of the desert.[5] Other mechanisms include indefinite immigration detention, increasing obstacles to applying for asylum system, channeling migrants into other countries, and threatening to stop aid to countries from which migrants flee.

Despite decades of escalating immigration restrictionism, in rhetoric, policies, and allocation of resources, migrants have not and will not stop crossing into the allegedly impenetrable U.S. Despite Sessions’s ruling, asylum lawyers still have opportunities to make claims for asylum seekers fleeing domestic violence and gang violence. Organizations and groups are increasingly revealing the treatment of migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border, at Mexico’s southern border, in detention centers, and everywhere in between. In other words, deterrence policies fail to do anything but intentionally inflict harm on migrants. At this critical moment of advocacy and analysis, I urge comprehensive research to examine and challenge the racialized and gendered violence of migration deterrence.

Notes

[1] Not all gangs are involved in drug trafficking, but such groups, whether hierarchically or loosely organized, thrive in the context of the conflictual environment between governments and drug trafficking cartels.

[2] See the work of Comision Nacional de los Derechos Humanos, Washington Office on Latin America, the report by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, and the Torn Apart/Separados digital humanities project with a directory of human rights “allies.”

[3] The Center for Gender and Refugee Studies generously gave me access to their data on gender asylum claims, and other data and publications are available through its website: https://cgrs.uchastings.edu/.

[4] See also the following feminist legal analysis by: Caroline McGee; Sara L. McKinnon; and sources recommended by the Center for Gender and Refugee Studies.

[5] I do not have room here to elaborate, but De León traces the racism behind U.S. policies of deterring migration through the weaponization of the desert; he and I share a theoretical commitment to uncovering how sovereign power is constituted through decisions to kill those deemed as unworthy and disposable.

References

De León, J. (2015). The Land of Open Graves: Living and Dying on the Migrant Trail. Oakland: University of California Press.

Nayak, M. and Suchland, J. (2006). ‘Gender Violence and Hegemonic Projects: Introduction,’ International Feminist Journal of Politics, 8 (4), pp. 467-485.

Nayak, M. (2015). Who is Worthy of Protection? Gender-Based Asylum and U.S. Immigration Politics. New York: Oxford University Press.

Valencia, S. (2018). Gore Capitalism. Translated by J. Pluecker. South Pasadena: Semiotext(e).

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Opinion – Covid-19 in Colombia: Migration, Armed Conflict and Gendered Violence

- Opinion – Tackling the Root Causes of Immigration to the US from Honduras

- New Warfare Domains and the Deterrence Theory Crisis

- Technologies of Truth and the LGBTI+ Asylum Reality

- Gendered Border Practices and Violence at the United States-Mexico Border

- Jus Post Bellum and Responsibilities to Refugees and Asylum Seekers