This is an excerpt from The Praeter-Colonial Mind: An Intellectual Journey Through the Back Alleys of Empire by Francisco Lobo. Download the book free of charge from E-International Relations.

In 2011, Stephen Spielberg produced another sci-fi narrative with a prehistoric flavor – Terra Nova, a tv production that despite its promise got canceled after only one season. It follows the exploits of a time-traveling family forced to escape an overpopulated and polluted planet Earth in 2149, making their way to a colony established 85 million years in the past. Their world is not only in the throes of combating climate disaster and demographic collapse; as expected, war is also part of this dystopian tale. More importantly, the leader of the colony, Commander Taylor, is a veteran of the 2138 Somalia War where he fought against such fictional foes as the ‘Axis’ and the ‘Russo- Chinese’. For a show that fell under most people’s radars, Terra Nova’s script does seem to capture some of the main struggles of our time – not least climate change, overpopulation, war, and great power competition. This ‘Russo-Chinese’ plotline, in particular, might have been made in a Hollywood basement, but it may yet become a reality in our present.

Russian-Chinese official relations date all the way back to the seventeenth century, when the Treaty of Nerchinsk was signed in 1689 (Becker Lorca 2015, 114). It was an agreement between two imperial powers, those of Tsarist Russia and Qing Dynasty China (Stent 2023, 255). Fast forward to the mid-twentieth century and the picture does not change much. ‘The Soviet Union of today is the China of tomorrow’. This was the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) official slogan for 1953, the same year Xi Jinping was born (Torigian 2024, para. 4). It was an aspirational slogan, adopted at a time when Chinese admiration for the Soviet model was at an all-time high.

Admittedly, following down the path chartered by the USSR meant not only boosting productivity and growth; it also entailed administering violence, lots of violence at home and abroad, by cracking down on domestic dissent and seeking territorial expansion of its sphere of influence, for the Soviet Union was a land empire in everything but name (Stent 2023, 31). Likewise, the People’s Republic of China aimed to regain its lost imperial grandeur following in the footsteps of its Russian ‘elder brothers’ (Ibid, 262), not only by furthering the communist ideology common to both, but also by displaying an unwavering commitment to the ‘One China’ policy (Maçães 2019, 141) whereby the territorial integrity of this modern-day land empire can only be accomplished if it engulfs Tibet, Hong Kong and Taiwan.

Further, despite their checkered past of cooperation as well as competition (Stent 2023, 253), Russia has openly expressed its support for the One China policy in a 2022 joint statement (Kremlin 2022) – issued only a few weeks before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine – where both nations portray themselves as world powers with rich cultural and historical heritage boasting thousand-years of experience of development. The two land empires likewise vow to defend their common adjacent regions from any type of external interference. This notorious statement underwriting a ‘no limits partnership’, in what has been characterized as ‘Eurasia’s authoritarian heartland’ (Torigian 2024, para. 28), is imbued with a spirit, not only of multipolarity and cooperation, but also of resistance and even defiance against perceived wrongs inflicted by certain ‘unilateral actors’, namely Western countries (Stent 2023, 254), in particular the US. As Bernard-Henri Lévy puts it, these former empires share ‘the same sense of being borne on the back of an incomparable past to which they will always be loyal’ (Lévy 2019, 139).

Yet, in their self-styled crusade against unfair treatment and historical humiliation, Russia and China have to find a way to come to terms with their own imperialist present, a cognitive dissonance that should not be hard to spot for the well-tuned praeter-colonial mind. Indeed, President Zelensky of Ukraine reminded the world of China’s active contributions to Russia’s expansionist war when he attended the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore in June of 2024. There, he called out both superpowers in unequivocal terms: ‘Russia, using Chinese influence on the region, using Chinese diplomats also, does everything to disrupt the peace summit’ (Tharoor 2024c, para. 5) that was to be held later that month in Switzerland. Further, Zelensky decried China’s material support for Russia in the form of components for the weapons used to wage its imperial war of aggression against Ukraine. A few months later, NATO would likewise call China out for being an ‘enabler’ of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine (NATO 2024).

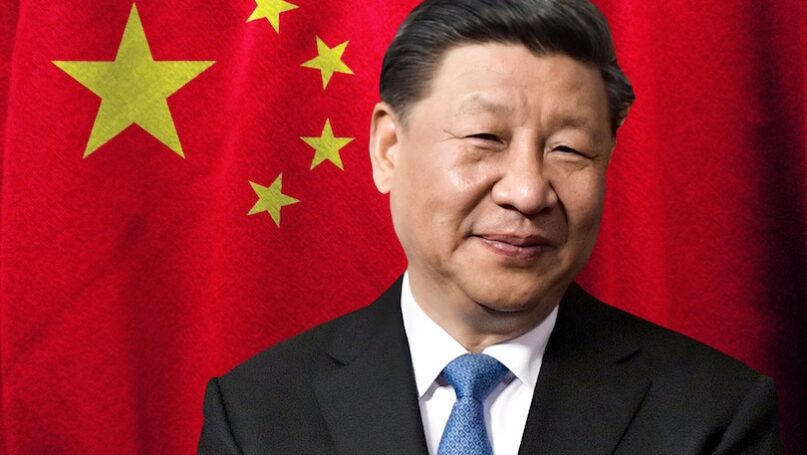

In this chapter, I would like to look at a fascinating case-study of a millenary empire-turned-client state-turned-emerging superpower that may yet rule the destinies of millions. In the words of one of history’s most hapless emperors, Napoleon Bonaparte: ‘Let China Sleep, for when she wakes, she will shake the world’. That day has finally arrived: China is now fully awake, and the praeter-colonial mind will have to make sense of the many implications of the release of this new-old imperialist force into the world.

One Hundred Years of Acritude

May the 4th is a day celebrated by millions to commemorate the valiant struggle for freedom by an oppressed people against an evil empire. I am not talking about Star Wars Day, although ‘May the 4th be with you’ is a popular phrase you will hear from the fans of the sci-fi franchise around the world every year as the calendar marks the fourth day of May. As it happens, 4 May is also a holiday celebrated in China to mark the anniversary of the student- led movement that challenged the government’s weak response to the Treaty of Versailles on 4 May, 1919, when the European powers decided that the territory of Shandong lost by Germany during the war would go, not back to the young Chinese Republic, but to the Japanese Empire (Laikwan 2024, 120). Today, May 4th marks ‘Youth Day’, an official holiday in the People’s Republic of China.

The loss of Shandong is but one episode in a long history of defeat and subjugation suffered by the Chinese people between the nineteenth and the twentieth centuries, beginning with the defeat in the First Opium War (1841- 1842) when the British Empire imposed by force the free trade of narcotics from India, while also taking Hong Kong for itself (Becker Lorca 2015, 116). After that, a streak of military defeats at the hands of Western and other powers would ensue (Laikwan 2024, 58), including the Second Opium War (1857–1860), the Sino-French War (1884–1885), the first Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), the War of the Eight-Nation Alliance (1900), and the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945), A.K.A. World War II.

These ten decades are known, and deeply remembered throughout China to this day, as the ‘century of humiliation’ (Allison 2017, 94; Maçães 2019, 165). To these military defeats and unforgiving post-bellum political arrangements we should add the endemic Sinophobia that was allowed to fester in the United States since the nineteenth century, as illustrated by Steinbeck’s character of Lee in East of Eden, and as formalized through official legislation like the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 banning all immigration to the US. After a revival of Sinophobia due to the Covid-19 pandemic, some see the same institutionalized prejudice behind current American legislation initiatives such as the Tik-Tok ban (Lan 2023).

I believe that, in order to understand what China wants and what it stands for in the twenty-first century, it is critical to understand this humiliation as the main driver of China’s foreign policy, as well as its relationship to a key concept in modern Chinese history, that of ‘revolution’. In a speech delivered in 2021 to mark the centennial of the Chinese Communist Party, Xi Jinping bemoaned the semi-colonial state China was reduced to after the First Opium War, while celebrating the armed revolution that eventually toppled the three counter-revolutionary ‘mountains’ of imperialism, feudalism, and capitalism (Laikwan 2024, 95).

The concept of revolution is at the heart of the CCP’s narrative of popular liberation and is deeply rooted in Chinese history and culture. Revolution or ‘geming’ is understood in China as a mandate from heaven, in the sense of a change of things that in actuality restores the universal order, much as one season is followed by another (Ibid, 83–84). Revolution is, in other words, self-evident natural law. In a similar sense, Fareed Zakaria identifies two meanings of the word ‘revolution’ in a recent monograph: (i) revolution in the sense of radical advance (e.g. the liberal revolutions in Europe and the US); and (ii) revolution as a return to the past, to the natural order of things (Zakaria 2024, 16–17). Zakaria points out that Trump is an example of the second type of nostalgic revolution, with his signature aspiration to ‘Make America Great Again’ (‘MAGA’), a political movement I shall address in the final chapter.

There is an important difference, however, between MAGA revolutionary nostalgia for the past and Xi’s: while MAGA aims at restoring a greatness supposedly lost, China’s ‘century of humiliation’ narrative seeks to redress something, to first right a wrong, so that restoration can then follow. Although Trump claims that America has indeed been wronged by the rest of the world (China included), the truth is that the streak of military defeats and political impositions that are a matter of record in recent Chinese history – and a very recent history at that, for a culture that can boast 5000 years of existence – have no equal in Western history, the closest to such a profound sense of collective humiliation being Weimar Germany after the Treaty of Versailles. Thus, what China wants – what Nazi Germany arguably also demanded – is respect, but of a special kind.

The philosopher Stephen Darwall once distinguished between ‘recognition respect’ – that which we owe to a person or an institution by virtue of a given accepted feature, for example, that we are all human, or that the law commands authority; and ‘appraisal respect’ – namely the respect we reserve only for a specific form of excellence or virtue, for instance, for an impressive athletic feat or a beautifully executed symphony (Darwall 1977). In that sense, China demands not only the ‘recognition respect’ that all the other 192 states members of the United Nations are entitled to by sole virtue of their condition as sovereign entities. What China wants is ‘appraisal respect’, as special consideration on account of its unique cultural and historical achievements. This is a kind of respect the post-colonialist activist may struggle to grasp in a system where all states are supposedly created equal, while at the same time some are ‘more equal’ than others, namely the P5 of which China is also a member. Conversely, the praeter-colonial mind is better equipped to entertain this paradox as contradiction lies at the heart of this particular mindset.

In order to exact this respect from the international community, China has followed two approaches, whether separately or combined. On the one hand, the ‘gentle’ approach is predicated on positive concepts such as the ‘Chinese Dream’, or a vision of national rejuvenation and territorial reunification (including the ‘inevitable’ seizure of Taiwan) (Laikwan 2024, 3). This approach is manifested in such indicators as the foundation of the National Soft Power Research Center in 2013 (the same year Xi became President of China), and the most recent successful exploration of the far side of the Moon in 2024. On the other hand, a ‘tougher’ approach can be observed in the development of a reportedly ultra-masculine style of doing things inside the country (Zakaria 2024, 270; Pesek 2023), as well as an assertive, vitriolic and even aggressive foreign policy carried out by ‘wolf warrior diplomats’ (Xiaolin and Yitong 2023), or diplomats performatively displaying a brand of ultra-sensitive nationalism abroad, inspired by the action movie franchise Wolf Warrior.

The New Westphalians

There is another concept, besides the memory of a ‘century of humiliation’ and the cure of ‘revolution’, that is key to understanding China’s position and aspirations in the world today. It is rooted in the ancient concept of ‘Heaven’ (‘Tian’) conceived not only as a supernatural place where deities dwell, but also as synonymous with propriety and natural or cosmic order, where all things are ‘properly placed and harmoniously related’ (Laikwan 2024, 29). Building on this notion, the idea of ‘All Under Heaven’ (‘Tianxia’) comes to the fore. Tianxia has been understood as a philosophy of universal peace and harmony among all nations; alternatively, and more interestingly for the praeter-colonial mind, it has also been denounced as imperialistic based on China’s self-perceived image as an ancient, superior civilization imposing a tributary system on what are considered lesser polities, as during most of China’s long history (Ibid; Maçães 2019, 33).

Tianxia is further thought of as territory as well as world order and culture (Laikwan 2024, 43), what Xi has called a ‘community of shared destiny’ (Maçães 2019, 26) akin to similar notions such as ‘spheres of co-prosperity’ or ‘spheres of influence’ of which another prominent example today is that of the ‘Russian World’ (‘Russkiy mir’ or ‘Русский мир’). As Pang Laikwan has recently put it: ‘Tianxia is an imagination of a relaxed cultural-political- territorial construct composed of trans-ethnic and trans-regional alliances’ (Laikwan 2024, 45).

Among such transnational initiatives we find what is perhaps the most notorious Chinese global scheme of the past decade, the ‘One Belt One Road’, a trade and infrastructure mega-project along the geographical lines of the old Silk Road in the ‘Greater Middle East’ (Kaplan 2023, xvi) and beyond, a sort of ‘Silk Road 2.0’. According to Bruno Maçães, ‘The Belt and Road is the name for a global order infused with Chinese political principles and placing China at its heart’ (Maçães 2019, 29–30). Although the Belt and Road is deliberately ‘informal, unstructured and opaque’ according to Maçães (Ibid, 34), the truth is that China has also become incredibly proficient at shaping the rules-based international order that is so precious to the West, thus following the recipe of Chinese thinker Wei Yuan (1794-1857): ‘learning from the strength of the barbarians in order to subdue the barbarians’ (Laikwan 2024, 59).

Indeed, as Mark Galeotti highlights, by not directly challenging the rules- based international order created after World War II, instead adroitly mastering its institutions and using its features and capabilities for the creation of new ones such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (of which Russia is also a member) or the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, ‘the Chinese are the true Westphalians now’ (Galeotti 2023, 205). Yet, this customization of the rules-based order to accommodate Chinese interests and grievances betrays the true spirit of international law as a normative system built on the values of respect for the human dignity and human rights of all. The existence of concentration camps within Chinese territory to ‘reeducate’ the Uyghur Muslim minority in the province of Xinjiang (Amnesty International 2021) is an open breach of said values.

Furthermore, although the West, and in particularly the US, is also guilty of selectivity and exceptionalism when it comes to the application and enforcement of the rules-based international order, as discussed previously, it remains to be seen whether China is capable of the same ‘virtuous hypocrisy’ as the West, considering that what we find there is a ‘rule by law’, not a ‘rule of law’ system (Tamanaha 2004, 91–113), or a ‘socialist rule of law with Chinese characteristics’ (Laikwan 2024, 97) where there is no guarantee that individual rights are adequately safeguarded or that checks and balances are in place to curtail power. Again, the Xinjiang concentration camps and the draconian anti-Covid measures imposed throughout the country stand as incontrovertible evidence of China’s disregard for human rights and individual freedoms.

In an era where international political alliances have become à la carte, like Zakaria points out (Zakaria 2024, 304), it remains the choice of the rest of the so-called ‘Global South’ to side with the countries and institutions where there exist a robust rule of law and healthy respect for human dignity, or to go live in supposed harmony ‘All Under Heaven’ but without any possible recourse against the designs sent from above.

The Art of War

In March of 2024, five months into the war in Gaza, the US decided to try something new and bold to alleviate the dire humanitarian situation on the ground: the construction of a floating pier as an alternative entry point to deliver aid. After only two months of operations, and having reportedly delivered only the equivalent of one day’s aid supplies by pre-war standards, the pier was scheduled to be decommissioned and dismantled. Critics point out the waste of resources and effort that went into this fanciful solution, when the land delivery route was perfectly usable were it not for lack of political will on the part of the Israelis. What critics don’t understand is that this was arguably never about Gaza, but about a different isolated piece of land surrounded by water, that is, an island located miles away from the Middle East and where around 10% of the global GDP originates: Taiwan.

Indeed, just as Xi sees China’s seizure of Taiwan as a historical inevitability, the West sees a major military confrontation with China as a result of said irredentism also highly likely. It is what Graham Allison (2017) has dubbed ‘the Thucydides’s trap’ – the situation that arises when a dominant hegemon is challenged by a rising power, for instance Sparta’s dominance being challenged by Athens, or the US place in the world being contested today by China. A potential war between the two powers has accordingly inspired highly realistic works of geopolitical fiction in recent years (Ackerman and Stavridis 2021; Ryan 2023). Thus, by building a pier in Gaza in 2024 the US was in actuality testing its ability to resupply any territory engulfed by water, especially one soon to be reclaimed by an assertive neighbor – one who also happens to be developing movable landing platforms of late.

It is arguably for the same geopolitical considerations that the US and its allies keep a strong presence in the theatre known as the ‘Indo-Pacific’, including in some post-colonial outposts making the news from time to time (to the anti-colonialist’s perplexion and rage), such as the UK’s ‘Last Colony’ (Sands 2022) in Chagos archipelago (where the US leases the Diego Garcia island as the site of a military base); or the French controlled New Caledonia. It is not mere love for tropical climates that keeps these Western powers stationed in the Indo-Pacific; it is grand strategy revamped, ‘The Great Game in the Pacific Islands’ (Sora et al 2024).

Xi of course denies China’s belligerency, even claiming as evidence that his people ‘do not carry aggressive traits in their genes’ (Laikwan 2024, 96) as yet another expedient of China’s exceptional place under heaven. However, as a compelling line from the play An Iliad by Lisa Peterson and Denis O’Hare reminds us: ‘We think of ourselves: not me, I’m not like that, I’m peaceful – but it happens anyway, some trick in our blood and – rage’ (Peterson and O’Hare 2014, 61). As Carl Schmitt reminds us (a fascist political theorist surprisingly popular among Chinese intellectuals today) (Laikwan 2024, 98), any difference or antitheses, whether big or small, but strong enough to reach the threshold of enmity, will bring about the basic political binary ‘friend/ enemy’ (Schmitt 2007, 37) – and, with it, war in its embryonic form, as Clausewitz also once noted (Clausewitz 2007, 100).

What can sometimes be taken as a mere joke, for example, Argentina’s pet name for its smaller neighbor Uruguay (‘provincia rebelde’ or ‘rebel province’), can in other contexts be deadly serious, such as when China similarly calls its own smaller neighbor a ‘breakaway province’ as the former remains poised to reclaim the latter by any means necessary. ‘By any means necessary’ means exactly that, and China has been incredibly proficient in the diversification of the many tools of diplomacy and war to attain its national goals – again, ‘learning from the strength of the barbarians to subdue the barbarians’. Thus, China has come to master what is known as ‘hybrid war’ (Regan and Sari 2024) combining all the so-called instruments of national power (Weber 2019) (i.e. Military, Informational, Diplomatic, Financial, Intelligence, Economic, Law, and Development). As PLA’s Colonels Qiao Liang and Wang Xiangsui wrote in the 1999 classic doctrinal text Unrestricted Warfare:

The expansion of the domain of warfare is a necessary consequence of the ever-expanding scope of human activity (…). The great fusion of technologies is impelling the domains of politics, economics, the military, culture, diplomacy, and religion to overlap each other. (…) Add to this the influence of the high tide of human rights consciousness on the morality of warfare. All of these things are rendering more and more obsolete the idea of confining warfare to the military domain (Qiao and Wang 1999, 189).

Building on the same doctrine, in 2003 the CCP and the Chinese Central Military Commission approved the concept of the ‘three warfares’ (‘san zhong zhanfa’), which amount to: 1) public opinion or media warfare (‘yuhun zhan’); 2) psychological warfare (‘xinli zhan’); and 3) legal warfare (‘falu zhan’) (Wortzel 2014, 29). The latter is also known in the West as ‘lawfare’; defined as ‘the strategy of using – or misusing – law as a substitute for traditional military means to achieve an operational objective’ (Dunlap 2008, 146). In principle, there is nothing wrong with using the law, or what is known in NATO as ‘legal operations’, as an instrument of national power to advance or reinforce the rule of law, namely ‘white legal ops’ (Vázquez Benítez 2020, 142), or lawfare conceived as ‘lawfair’ (Galeotti 2023, 151). It is when legal rules are bent and abused to erode the rule of law that this becomes problematic (i.e. ‘black legal ops’).

In recent years, China has become skilled at waging lawfare to advance its interests in the Indo-Pacific through black legal ops, including what has been characterized as a ‘legal blitzkrieg’ in Hong Kong (Ming-Sung 2020) – through increasingly oppressive national security legislation to crash political dissent and curtail human rights – and a veritable ‘legal imperialism’ whereby it uses juridical arguments and artifices to occupy and claim for itself sizable portions of the South China Sea. Galeotti describes this strategy in the following terms:

Time and again, Beijing’s gambits have been ruled out of order by international courts and arbitration, but it continues to use the forms and language of the law in what is nothing other than a naked land – sea – grab. So why do it? One of the great strengths of lawfare is precisely in the mind games it permits, confusing the issues, obscuring aggression and above all tying law-abiding states up in knots of their own making. In practice, this is straightforward imperialism. However, Beijing has been smart enough to dress it up in judges’ robes, fishermen’s oilskins and coast guard blues. It presents a spurious but determined front of legality (Galeotti 2023, 146).

Finally, it is worth noting that, in addition to hybrid, non-kinetic forms of warfare, China has also been preparing for traditional, kinetic warfare in a most peculiar way. Since it has not been engaged in a major international armed conflict since its inception in 1949 – other than border skirmishes with neighbors, including with the extinct USSR and India, and the brief 1979 Sino-Vietnamese War – the People’s Republic of China has in recent decades stepped up its game in the field of peacekeeping operations. Accordingly, the CCP claims that ‘World peace is indivisible and humanity shares a common destiny’ (China Military Online 2022).

Yet, this ostensibly humanitarian spirit is arguably combined with more pragmatic considerations, namely a chance for Chinese troops to gain some field experience for when the time comes to fight a real war (Lambert 2024), a department in which the US can be said to be leaps and bounds ahead of its main competitor. China knows this, and so it has decided to prepare for war by using the devices of peace. Si vis bellum para pacem. Thus, whether by traditional or hybrid means, both the US and China are preparing for the next big geopolitical confrontation, as they draw parallels and lessons from the current ‘big show’, the war in Ukraine. As the Prime Minister of Japan has put it: ‘Today’s Ukraine could be East Asia tomorrow’ (DSEI Japan 2025).

Indeed, although they are separated by geography, history, and culture, some in Washington see Kyiv and Taipei as ‘geopolitical neighbors’ (Tharoor 2024b, para. 1), while both Taiwan and China are taking notes of the West’s reaction in Ukraine. This last connection is as important as ever, since China’s foreign policy today is not shaped only by resentment and pride, but also by that same existential anxiety Ukraine and Taiwan experience now. This anxiety was instilled in China over a century ago when it woke from its dream of greatness (Laikwan 2024, 185). Although 5000 years of history is a long time compared to which one century of humiliation should be but a hiccup, the truth is that, precisely because we start measuring China’s journey 5000 years in the past, then one hundred years ago happened only yesterday and the long arc of history has not had the chance to fully heal that wound.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Continuity and Change: China’s Assertiveness in the South China Sea

- Is China Under-Exploiting One Legal Avenue in the South China Sea?

- The Implications of China’s Growing Military Strength on the Global Maritime Security Order

- The Taiwan Factor in the Clarification of China’s U-shaped Line

- Legitimacy and Nationalism: China’s Motivations and the Dangers of Assumptions

- Asian Security amid China’s Dominance