This is an excerpt from The United Nations: Friend or Foe of Self-Determination? Get your free copy here.

Whether the United Nations (UN) discourages or encourages self-determination of peoples is a question that is not easy to answer. The position of the UN on self-determination must first be distilled from General Assembly (GA) and Security Council (SC) resolutions and the case law of the International Court of Justice (ICJ). International law on self-determination is criticised for being vague; UN GA Resolution 1514 (XV) (1960), Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples, suggests, for example, both by the wording of the title and the preamble, that the intended subject of the resolution would be colonial peoples. Nevertheless, the drafters of the text chose to use general terms (‘all peoples have the right to self-determination […]’ and ‘Convinced that all peoples have an inalienable right to complete freedom, the exercise of their sovereignty and the integrity of their national territory’). International law on self-determination is also criticised for representing the interests of existing states and thus protecting the status quo in international relations. Furthermore, the answer to the question of whether the UN discourages or encourages self-determination depends on what form of self-determination we are talking about: internal or external self-determination? According to Senese (1989, 19) external self-determination is the idea ‘that each people has the right to constitute itself a nation-state or to integrate into, or federate with, an existing state’ and internal self-determination refers to ‘the right of people to freely choose their own political, economic, and social system’. This does not necessarily require the creation of a new state but can be achieved by receiving autonomy inside existing states.

In this contribution, we argue that the current international legal framework, referred to as the UN paradigm, has a number of shortcomings and is therefore inadequate to answer modern claims involving self-determination, such as the Cyprus conflict. Although internal self-determination is encouraged in limited circumstances, we argue that this approach fundamentally disregards other interests besides state interests and is therefore not able to bring the long-lasting Cyprus conflict to an end. Would alternative approaches to self-determination be more successful?

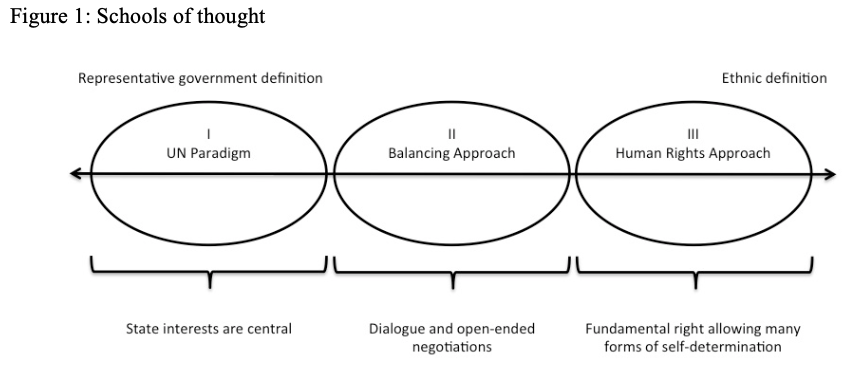

Inspired by Musgrave’s (1997, 148–167) initial distinction between definitions of a people, we explored alternative views on self-determination found in academic literature. These views could be grouped under at least two other schools of thought outside the UN framework (Figure 1). One of these, the balancing approach, suggests that finding a sustainable solution to a conflict should be attempted by respecting and balancing the interests of all groups involved. The outcome of such negotiations is much more open than under the UN approach. The other school, the human rights approach, sees self-determination as a fundamental human right that could hypothetically belong to every ethnic group under very different circumstances. They define a people on the basis of subjective factors of self-consciousness, thereby focusing on ethnic criteria and identifying factors such as a shared history, language, religion and geographical, economic and quantitative factors.

Each of these schools of thought has consequences for the circumstances in which a successful claim to self-determination can be made, and for the range of peoples that may rightfully do so. To answer the question of whether the UN discourages or encourages self-determination, we will describe how the UN paradigm has fared in the Cyprus conflict. We will then see if either of the other schools offers a better resolution to this conflict than the UN approach does.

The Cyprus Conflict in a Nutshell

Cyprus is an excellent case study of how different visions of self-determination could apply to post-colonial situations. Discussions about the constitutional future of Cyprus were organised after the Second World War. Britain, as the formal administrator of Cyprus, proposed partition of the island, but this idea was refused not only by Greek and Turkish Cypriots themselves, but also by the international community. Greek Cypriots had been advocating their desire for the union of the island with Greece (enosis). This in turn led to a Turkish Cypriot call for partition, and thus for Turkish Cypriot independence. The goals of Greek Cypriot irredentism and Turkish Cypriot separation have been totally irreconcilable, yet both have been justified by reference to self-determination (Musgrave 1997, 227).

In 1960, Cyprus became a republic with a constitution based on the political representation of both Cypriot communities. However, political tensions between the two communities remained. Since the outbreak of violence and consequent 1974 division of Cyprus into northern Turkish and southern Greek parts, the UN undertook several efforts to reunite the island under one political administration. Both communities took turns rejecting UN proposals for reconciliation and the reinstitution of a bi-communal (con)federation.[1] See for example UN GA Resolution 37/253 (1983) where the General Assembly deplores the current state of affairs and calls for the continuation of constructive bi-communal deliberate efforts.

In 1983, the Turkish Cypriot Parliament unanimously proclaimed an independent Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), which was immediately condemned by the Security Council in Resolutions S/RES/541 (1983) and S/RES/550 (1984). The Annan plan was the latest serious effort by the UN to unify Cyprus; it and can be found in report S/2004/437 (2004) of the Secretary-General on his mission of good offices in Cyprus. However, Greek Cyprus rejected this plan in 2004. Later attempts, not only by the UN and by the leaders of the Greek and Turkish Cypriot communities, but also by the European Union, did not amount to much either. Thus, the story of a divided Cyprus continues.

UN Paradigm

As the first school of thought, the UN paradigm represents the current and general interpretation of self-determination held by the main organs of the UN. This approach is also supported by contributions in academic literature (Brilmayer 1991, 177–202; Buchanan 2004, 205–208; Gudeleviciute 2005, 48–74; Kirgis 1994, 308). First, we will discuss the general position of the UN with respect to self-determination. Then, we will see how the UN paradigm fared in the context of the Cyprus conflict.

UN Practice

In a sense, the UN has been an advocate of self-determination. Much is owed to the UN for advancing the development of self-determination from a political principle into a legal right, for example by including self-determination as one of the organisation’s purposes in the UN Charter.[2] Also in later UN GA resolutions, the right was recognised as a human right and fundamental principle of international law; for example: the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, GA Resolution 217A (III) of 10 December 1948; the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries, GA Resolution 1514 (XV) of 14 December 1960; the International Covenants on Civil and Political Rights and on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, GA Resolution 2200 (XXI) of 16 December 1966; the Declaration on Principles of International Law Concerning Friendly Relations and Cooperation Among States in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations, GA Resolution 2625 (XXV) of 24 October 1970; the Declaration on the Occasion of the 50th Anniversary of the UN, GA Resolution 50/6 of 24 October 1995.

The effect of these political acts of the UN has perhaps been clearest with respect to the widespread wave of anti-colonialism that went through the world, culminating in the assertion of the right by many colonial peoples in the period from the 1940s to the 1960s. The ICJ, in landmark cases such as the Namibia, Western Sahara, and East Timor cases, approved of the exercise of self-determination by peoples under colonial or foreign occupation.[3] It has also emphasised that self-determination is an erga omnes right, which means that it can be asserted against any state that infringes this fundamental people’s right.[4] Moreover, the ICJ clarified that the right also applies outside the colonial framework, however, within the territorial framework of independent states.[5]

Despite these positive contributions, the UN’s practice also suffers from shortcomings and indeterminacies. For example, none of the UN’s resolutions contain a formal distinction between internal or external self-determination. Neither does the ICJ, in its extensive set of judgments, make this distinction, nor does it give legal clarification of the circumstances required for a successful claim to external self-determination outside a colonial context. In the Secession of Quebec[6] case, the Canadian Supreme Court restated common UN practice, emphasising that ‘international law expects that the right to self-determination will be exercised by peoples within the framework of existing sovereign states and consistently with the maintenance of the territorial integrity of those states [emphasis added], respecting its borders as they have been since independence, in accordance with the principle of uti possidetis iuris. The UN has indeed consistently opposed any attempt at the partial or total disruption of the national unity and territorial integrity of a country for reason of maintaining international peace and stability (Shaw 2017, 202). This raises questions of legitimacy and representativeness, especially if these borders were drawn by former occupying parties regardless of historical or ethnic claims to the territory.

While there have been cases in which the ICJ approved of the use of external self-determination, for example in the Palestinian Wall case[7], this seems to be limited to situations in which human rights are violated as a result of foreign military intervention, aggression, or occupation (including colonialism), or in the most extreme of cases including formal underrepresentation of a minority and serious violations of human rights.[8] Kirgis (1994, 308) formulates this view in the following way:

If a government is at the high end of the scale of democracy, the only self-determination claims that will be given international credence are those with minimal destabilising effect. If a government is extremely unrepresentative, much more destabilising self-determination claims may well be recognised.

In all other cases, the population of a territory may internally pursue political, economic, social, and cultural development through a participatory democratic process. Moreover, the UN and other international organisations have developed some legal frameworks to protect minorities inside existing states. See for example the Copenhagen Document of what was then called the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (29 June 1990), a charter for regional and minority languages (5 June 1992) and a framework convention for national minorities (February 1995) of the Council of Europe (both entered into force in 1998) and a GA Declaration 47/135 on the rights of persons belonging to certain minorities. Thus, despite promoting the importance of self-determination of all peoples in its official documents, the UN seems to adopt a rather conservative approach in practice. State interests generally prevail over the subjective interests of groups in society, so as to prevent the independence and stability of states from being endangered by the challenging of frontiers.

The emphasis on state interests is also reflected in the UN’s involvement in peace agreements and negotiations following conflicts concerning claims of self-determination. Although the UN generally takes an optimistic approach by inviting both sides of the conflict into a mediation process, emphasising the importance of non-violent conflict resolution, it nevertheless directs the entire process and does not allow for deviations by either party from the peace agreement. Crucial in this process is the maintenance of political stability and security of state boundaries; see for example S/RES/1410 (2002) on the establishment of a United Nations Mission of Support in East Timor (UNMISET). Full cooperation of both government and rebellion groups is mandatory and should ideally lead to an inclusive democratic restructuring, thus excluding options that involve territorial changes or extensive political alterations.

Applied to the Cyprus Conflict

How does the UN paradigm fare in the context of the Cyprus conflict? Both key aspects of the UN paradigm – maintaining territorial integrity and interpreting self-determination as an encompassing democratic process – have shaped the UN’s policy in the Cyprus conflict. As far back as the late 1950s, when the British proposed partition of the island as the most viable solution to the conflict, the GA asserted their opposition to partition, and therefore external self-determination (Kattan 2015, 22–23). Prior to the colonial declaration (1960), partition was seen as a method or technique of decolonisation and had been applied in a number of cases, for example in the Japanese colony of Korea and French Indochina in 1945 and in British India in 1947 (ibid.). Consecutive resolutions urged the involved parties to respect the full sovereignty, independence, territorial integrity and non-alignment of the Republic of Cyprus and to cease any form of interference with internal affairs.[9] In S/RES/367 (1975) and S/RES/1251 (1999), any attempts at unification with another state or at the partition of the island were expressly condemned. Moreover, the UN SC stated its expectations in S/RES/1251 (1999) about a Cyprus settlement as follows: ‘[it] must be based on a State of Cyprus with a single sovereignty and international personality and a single citizenship, with its independence and territorial integrity safeguarded, and comprising two politically equal communities […].’ General state interests, meaning keeping the territory intact, have thus prevailed over either community’s wishes of partition or unification.

From this perspective it makes sense that the UN SC immediately rejected the unilaterally proclaimed independence of the TRNC in S/RES/541 (1983) and repeated in S/RES/550 (1984). Instead, the Greek-Cypriot government of Cyprus has been regarded as the single representative administration of the entire island until today. In 1993, Greek Cyprus entered into negotiations with the European Union to assess eligibility to European Union membership. In the same year, the European Court of Justice imposed a trade embargo on the TRNC. As tensions on the island remain, the UN SC keeps urging the communities to commit to finding a sustainable solution because the status quo is unacceptable. On this basis, the UN Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus (UNFICYP) is also continued on a yearly basis as confirmed in the latest Resolution S/RES/2453 (2019). Solving the conflict is considered an internal affair that should be solved by both communities on an equal basis and comprising the entire population on the island. In 2001, it was estimated that the ratio of Greek and Turkish Cypriots on the island is nearly 80% to 20% respectively (World Population Review 2019). However, determining the exact number of Greek and Turkish Cypriots is not an easy thing and numbers vary. It is unclear who actually counts as a Greek or a Turkish Cypriot. Additionally, both parties tend to exaggerate their own number in this ‘war of numbers’ (Hatay 2007, 4). Despite numerical differences between the communities, both are referred to by the UN as together being one people. In this way, the UN clearly sees self-determination as an encompassing democratic process.

It is uncertain whether the Cyprus conflict can be solved in the near future as long as the UN paradigm constitutes the standard interpretation. Both communities are confronted with an imposed form of self-determination that depends on their collaboration, while they are scarcely on speaking terms. Maintaining the TRNC does not fit into the picture; the Turkish Cypriots can only receive international recognition for invoking the right to external self-determination if they fall under the exceptional circumstances of non-representation or gross human rights violations. Since UN representatives have made numerous attempts to reconcile both groups, hearing their political expectations and concerns, these exceptional circumstances do not exist. To conclude, the continuous efforts of the UN to bring both communities together into one state structure is an ambitious, but also an unattainable goal which keeps negotiations in a stalemate.

Alternative Approaches

The two alternative views that we composed from academic literature – the balancing and the human rights approach – are both more accommodating towards self-determination than the UN paradigm. The balancing approach discourages the creation of fixed categories of people, and the development of a rigid single legal framework. Rather, flexibility is recommended when it comes to evaluating diverse claims to both internal and external self-determination. The state is no longer considered the most important factor in (inter)national affairs. The human rights approach even takes it a step further by seeing self-determination as a group right potentially belonging to diverse nations or ethnic groups living in the same state. These groups have the right to defend their identities and claims to self-determination must be taken seriously. It therefore takes a sympathetic attitude towards both internal and external forms of self-determination. Both schools will be discussed below.

Balancing Approach

In the balancing approach, flexibility is central. Proponents of this approach argue that neither complete adherence to territorial integrity nor unconditional approval of external self-determination can assure satisfaction on all sides of a dispute (Babbitt 2006; Cassese 1995; Griffiths 2003; Hannum 2006; Horowitz 1998; McCorquodale 1994). Thus, in each specific situation, a negotiation or reconciliation process involving all parties is recommended. By consent, the parties can choose either to terminate the struggle for self-determination, or to allow for increased internal political rights and autonomy. Claims for external self-determination could even overrule territorial integrity.

Hannum (2006, 76–77), for example, argues that the international community should look for the most appropriate solution to separatist aspirations, in exceptional cases allowing for the creation of a new state. In a similar vein Cassese (1995, 344–362) argues, that the regulation of the right to self-determination is blind to the demands of ethnic groups, and national, religious, cultural, or linguistic minorities, who often find themselves unequipped with rights to improve their situation within existing states. He wants international customary law to develop in such a way as to allow for the free and genuine choice of government in addition to the static model of representative government adopted by the UN. Robert McCorquodale (1994) suggests considering the concept of self-determination as a human right but limited in scope by compelling societal interests, which are protected by the state, but may under no circumstances lead to the oppression of peoples. Horowitz (1998, 181) emphasises that the solution to ethnic territorial claims requires careful balancing to accommodate all interests involved. He suggests that external self-determination would not likely be in everyone’s benefit. Martin Griffiths (200, 3) agrees that aspirations to secession are permissible under certain circumstances. Since secession is generally unable to provide the most agreeable solution and will often even appear inadequate, he calls to consider alternatives for secession, such as minority rights. To summarise in the words of Eileen Babbitt (2006, 165):

As we gain greater understanding of the causes of self-determination conflicts and a better appreciation of the many alternatives that might be put forward to resolve these conflicts, ‘negotiating self-determination’ may become the norm, rather than the exception.

Balancing Approach Applied to the Cyprus Conflict

Taking a balanced approach to the Cyprus question would first mean not rejecting the aspirations of the Turkish Cypriots to self-determination outright as the UN approach basically does. The goal would be a peaceful solution with which all parties can live, negotiated between the parties. Third parties are helpful if they act as impartial mediators who facilitate meetings between representatives of both sides. Under this approach, an international forum of negotiation would be established. However, contrary to the UN attempts, territorial integrity would not be the ultimate goal. Instead, the outcome is open-ended and could be the status quo, regional autonomy or external self-determination. The revival of the 1960s bi-communal state structure would be a viable option, as would the creation of two states or becoming part of Turkey or Greece. Following the balancing approach, finding the most appropriate solution to the conflict and creating (a) safe and stable political unit(s) on the island in which both peoples are respected and at least sufficiently satisfied, should be an ultimate goal.

Human Rights Approach

The human rights approach comprises diverse critical positions in academic literature against the current standard interpretation of self-determination (Koskenniemi 1994; Margalit and Raz 1990; Pavković 2003; Philpott 1995). Instead of seeing self-determination as a democratic process that involves an entire population, as the UN does, the human rights approach focuses on ethnicity and nationality as the binding elements in societies. According to Daniel Philpott (1995, 353), self-determination is equally essential to a people as is freedom to an individual. For a group, it is the most important instrument in the process of social growth towards their specific social (or economic, legal, political) ideals. As self-determination is a human right that belongs to every (ethnic) group, this approach is also very lenient on the admissibility of many forms of self-determination to assert this right in practice. For instance, secession from an existing state could be an option under certain circumstances. However, a necessary restriction of the prima facie right to self-determination is sought by each author from a different perspective; all groups of peoples do possess a fundamental right to self-determination, but it would not be preferential if each group were in a position to assert this right.

Margalit and Raz (1990, 439–461), for example, find the necessary restriction in the applicability of ethnic and social factors. Self-determination would qualify as an instrument for social groups to retain or preserve their identity and to protect themselves against (cultural) oppression by other cultures. It is a right that may belong to a group that forms a majority in a certain territory and shares the same political ideal (Margalit and Raz 1990, 457):

That importance makes it reasonable to let the encompassing group that forms a substantial majority in a territory have the right to determine whether that territory shall form an independent state in order to protect the culture and self-respect of the group, provided that the new state is likely to respect the fundamental interests of its inhabitants, and provided that measures are adopted to prevent its creation from gravely damaging the just interests of other countries.

In this view, the possibility of changes in a state’s territory is made subordinate to subjective group interests, provided that the group acts responsibly.

Human Rights Approach Applied to the Cyprus Conflict

In general, the human rights approach seems most promising to minorities within states that wish to pursue their political aspirations. The notion of cultural distinctness of a group, which is central to the human rights approach, implies that the Greek-Cypriot and the Turkish-Cypriot communities should not be considered one people. Both communities differ on aspects of ethnicity, language, culture, and history. They have a different set of social ideals and have different ideas about how politics or law can accommodate their group identity. From this perspective, the UN’s solution, namely, forcing these distinct groups to commit to the same political ideas under one constitution, appears unrealistic. Both the Greek-Cypriot and the Turkish-Cypriot communities may qualify as encompassing groups as they constitute a numerical majority on their respective territories on the island. If they acted responsibly and represented the political will of the majority, then external self-determination could be a vital method in the preservation of each group’s identity and cultural distinctness. There would be more respect and understanding from the international community for the Turkish-Cypriot feeling of cultural distinctness and, accordingly, their declaration of the TRNC. Since the human rights approach adopts a less fixed notion of the execution of the right to self-determination, diverse claims of self-determination can be made – including secession. In this respect, the division of the island along the lines of the two communities could be a viable solution to the conflict.

Conclusions

So, does the UN discourage or encourage self-determination of peoples? Under the exceptional circumstances of the decolonisation process, the UN supported self-determination of colonial peoples. Nowadays, the UN has a clear preference for internal over external self-determination. Especially in the last decade of the twentieth century, efforts have been made – not only by the UN – to ensure that minorities should enjoy the greatest amount of self-determination as is possible in their particular situation. Thus, alternative solutions to secession have been created. This way, the state would remain intact, but a political process of devolution and the granting of partial autonomy would meet minorities in their aspirations to self-determination. When it comes to external self-determination, however, the UN is more reluctant to give in. Claims to secession take second place behind the territorial integrity of a state. For the Cyprus conflict this means that a single state including both communities is the only acceptable solution.

The alternative approaches suggested in the academic literature are much less state-centric and more favourable towards external self-determination. When compared to these approaches, the UN approach looks like a strong opponent of external self-determination. Although looking at the Cyprus conflict through the eyes of the alternative approaches revealed different solutions that cannot be imagined under the UN paradigm, they are far from providing a realistic solution to the conflict. For any of the alternative approaches to have a real impact on international politics, a paradigm shift supported by the international community away from the UN paradigm towards one of the alternative approaches has to occur.

Notes

[1] www.cyprusun.org provides an overview of GA and SC resolutions concerning the Cyprus conflict (Cyprusun 2012).

[2] See articles 1(2), 55, and Chapters XI, XII, XIII of the Charter, which provide regulations with regard to non-self-governing territories.

[3] See the Namibia case (Legal Consequences for States of the Continued Presence of South Africa in Namibia (South West Africa)) notwithstanding Security Council Resolution 276 (1970), Advisory Opinion, I.C.J. Reports 1971, 16), the Western Sahara case (Western Sahara, Advisory Opinion, I.C.J. Reports 1975, 12) and the East Timor case (East Timor (Portugal v. Australia), Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1995, 90), all concerning decolonization.

[4] See the East Timor case (East Timor (Portugal v. Australia), Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1995, 90) par. 29, the Barcelona Traction case (Barcelona Traction, Light and Power Company, Limited, Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1970, 3) par. 33, and the advisory opinion in the Palestinian Wall case (Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Advisory Opinion, I.C.J. Reports 2004, 136) par. 88.

[5] Burkina Faso v. Republic of Mali case, Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1986, 554–567, supported by the Canadian Supreme Court in the Secession of Quebec case, Reference re Secession of Quebec, [1998] 2 SCR 217, 1998 CanLII 793 (SCC).

[6] Secession of Quebec case, Reference re Secession of Quebec, [1998] 2 SCR 217, 1998 CanLII 793 (SCC). Emphasis added. The principle of uti possidetis iuris was also mentioned in relation to self-determination in the Burkina Faso v. Mali case (I.C.J. Reports 1986, 554–567), and the Arbitration Commission of the European Conference on Yugoslavia, Opinion no. 2, 92 ILR, 167–168.

[7] Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Advisory Opinion (I.C.J. Reports 2004, 136).

[8] GA Resolution 72/159 of 19 December 2017, on the universal realization of the right of peoples to self-determination.

[9] See primarily UN GA Resolution 3212 (1974) and UN SC Resolution 365 (1974), and subsequent resolutions.

References

Babbitt, Eileen F. 2006. “Negotiating Self-Determination. Is it a Viable Alternative to Violence?”. In Negotiating Self-Determination, edited by Hurst Hannum and Eileen F. Babbitt, 159–165. Lanham: Lexington Books.

Brilmayer, Lea. 1991. “Secession and Self-Determination: a Territorial Interpretation.” Yale Journal of International Law 16: 177–202.

Buchanan, Allen. 2004. Justice, Legitimacy, and Self-Determination. Moral Foundations for International Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cassese, Antonio. 1995. Self-Determination of Peoples: A Legal Reappraisal. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe. 1990. Document of the Copenhagen meeting of the Conference on the Human Dimension of the CSCE, available from https://www.osce.org/odihr/elections/14304?download=true.

Council of Europe. 1992. European Charter for Regional and Minority Languages. European Treaty Series-No. 148, available from https://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list/-/conventions/rms/0900001680695175.

Council of Europe. 1995. Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities and Explanatory Report. H (95) 10, available from https://rm.coe.int/CoERMPublicCommonSearchServices/DisplayDCTMContent?documentId=09000016800c10cf.

Cyprusun. 2012. “UN Documents on Cyprus – Reports”. Accessed June 31, 2019. http://www.cyprusun.org/?cat=52.

General Assembly Resolution 217A (III), International bill of human rights – universal declaration of human rights, A/RES/217(III) (10 December 1948), available from https://undocs.org/en/A/RES/217(III).

General Assembly Resolution 1514 (XV), Declaration of the granting of independence to colonial countries and peoples, A/RES/1514(XV) (14 December 1960), available from https://undocs.org/en/A/RES/1514(XV).

General Assembly Resolution 2200 (XXI), International covenants on civil and political rights and on economic, social and cultural rights, A/RES/2200 (XXI) (16 December 1966), available from https://undocs.org/en/A/RES/2200(XXI).

General Assembly Resolution 2625 (XXV), Declaration on principles of international law concerning friendly relations and cooperation among states in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations, A/RES/2625(XXV) (24 October 1970), available from https://undocs.org/en/A/RES/2625(XXV).

General Assembly Resolution 3212 (XXIX), Questions of Cyprus, A/RES/3212 (XXIX) (1 November 1974), available from https://undocs.org/en/A/RES/3212(XXIX).

General Assembly Resolution 37/253, Question of Cyprus, A/RES/37/253 (13 May 1983), available from https://undocs.org/en/A/RES/37/253.

General Assembly Resolution 47/135, Declaration on the rights of persons belonging to national or ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities, A/RES/47/135 (18 December 1992), available from https://www.un.org/documents/ga/res/47/a47r135.htm.

General Assembly Resolution 50/6, Declaration on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the United Nations, A/RES/50/6 (24 October 1995), available from https://undocs.org/en/A/RES/50/6.

General Assembly Resolution 72/159, Universal realization of the right of peoples to self-determination, A/RES/72/159 (19 December 2017), available from https://undocs.org/en/A/RES/72/159.

Gudeleviciute, Vita. 2005. “Does the principle of self-determination prevail over the principle of territorial integrity?” International Journal of Baltic Law 2 (2): 48–74.

Griffiths, Martin. 2003. “Self-Determination, International Society and World Order.” Macquarie Law Journal 3: 29–49.

Hannum, Hurst. 2006. “Self-Determination in the Twenty-First Century.” In Negotiating Self-Determination, edited by Hurst Hannum and Eileen F. Babbitt, 61–80. Lanham: Lexington Books.

Hatay, Mete. 2007. “Is the Turkish Cypriot Population Shrinking? An Overview of the Ethno-Demography of Cyprus in the Light of the Preliminary Results of the 2006 Turkish-Cypriot Census.” International Peace Research Institute: Oslo. https://www.prio.org/Global/upload/Cyprus/Publications/Is%20the%20Turkish%20Cypriot%20Population%20Shrinking.pdf.

Horowitz, Donald L. 1998. “Self-Determination: Politics, Philosophy, and Law.” In National Self-Determination and Secession, edited by Margaret Moore, 181–215. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kattan, Victor. 2015. “Self-Determination during the Cold War: UN General Assembly Resolution 1514 (1960), the Prohibition of Partition, and the Establishment of the British Indian Ocean Territory (1965).” Max Planck Yearbook of United Nations Law 19: 419–468.

Kirgis, Frederic L. Jr. 1994. “The Degrees of Self-Determination in the United Nations Era.” The American Journal of International Law 88 (2): 304–310.

Koskenniemi, Martti. 1994. “National Self-Determination Today: Problems of Legal Theory and Practice.” International and Comparative Law Quarterly 43 (2): 241–269.

Margalit, Avishai and Joseph Raz. 1990. “National Self-Determination.” The Journal of Philosophy 87 (9): 439–461.

McCorquodale, Robert. 1994. “Self-Determination: A Human Rights Approach.” The International and Comparative Law Quarterly 43 (4): 857–885.

Musgrave, Thomas. D. 1997. Self-Determination and National Minorities. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pavković, Aleksandar. 2003. “Secession, Majority Rule and Equal Rights: A Few Questions.” Macquarie Law Journal 3: 73–94.

Philpott, Daniel. 1995. “In Defence of Self-Determination.” Ethics 105 (2): 352–385.

Security Council report 2004/437, Report of the Secretary-General on his mission of good offices in Cyprus, S/2004/437 (28 May 2004), available from https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N04/361/53/PDF/N0436153.pdf?.

Security Council Resolution 276, The situation in Namibia, S/RES/276 (30 January 1070), available from http://unscr.com/en/Resolutions/doc/276.

Security Council Resolution 365, Cyprus, S/RES/365 (13 December1974).

Security Council Resolution 367, Cyprus, S/RES/367 (12 March 1975) available from https://undocs.org/S/RES/367.

Security Council Resolution 541, Cyprus, S/RES/541 (18 November 1983).

Security Council Resolution 550, Cyprus, S/RES/550 (11 May 1984), available from https://undocs.org/S/RES/550 (1984).

Security Council Resolution 1251, Cyprus, S/RES/1251 (29 June 1999) available from https://undocs.org/S/RES/1251 (1999).

Security Council Resolution 1410, East Timor, S/RES/1410 (17 May 2002), available from https://undocs.org/S/RES/1410 (2002).

Security Council Resolution 2453, The situation in Cyprus, S/RES/2453 (30 January 2019), available from https://undocs.org/S/RES/2453 (2019).

Senese, Salvatore. 1989. “External and Internal Self-Determination.” Social Justice 16 (1): 19–25.

Shaw, Malcolm N. 2017. International Law. 8th edition. Cambridge: University Press.

United Nations. 1945. Charter of the United Nations and Statute of the International Court of Justice (adopted 26 June 1945, entered into force 23 March 1945) 59 Stat. 1031, available from https://www.un.org/en/sections/un-charter/introductory-note/index.html.

World Population Review. 2019. “Population Cyprus”. Accessed June 32, 2019. http://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/cyprus-population/.

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- The UN as Both Foe and Friend to Indigenous Peoples and Self-Determination

- The Precarious History of the UN towards Self-Determination

- Opinion – Attacks on UN Peacekeepers in Cyprus Threaten a Fragile Status Quo

- Turkey and the Eastern Mediterranean: A Chance for Cooperation or a Warning of Conflict?

- National Responses to the Syrian Refugee Crisis: The Cases of Israel and Cyprus

- Could Trump and Putin Solve the Cyprus Conflict?