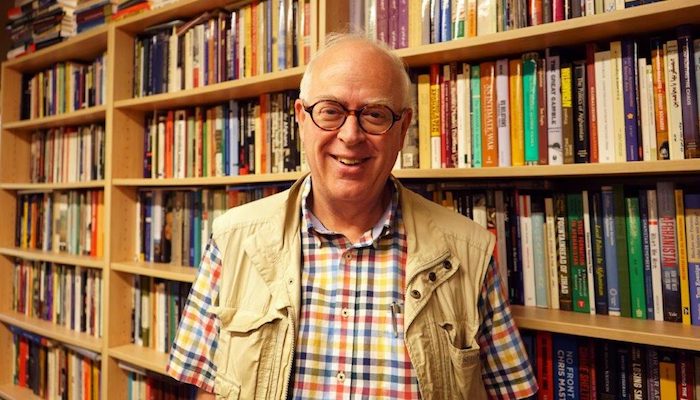

Professor William Maley is Professor of Diplomacy at the Asia-Pacific College of Diplomacy, where he served as Foundation Director from 1 July 2003 to 31 December 2014. He taught for many years in the School of Politics, University College, University of New South Wales, Australian Defence Force Academy, and has served as a Visiting Professor at the Russian Diplomatic Academy, a Visiting Fellow at the Centre for the Study of Public Policy at the University of Strathclyde, and a Visiting Research Fellow in the Refugee Studies Programme at Oxford University. He is a Barrister of the High Court of Australia, Vice-President of the Refugee Council of Australia, and a member of the Australian Committee of the Council for Security Cooperation in the Asia Pacific (CSCAP). He is also a member of the International Advisory Board of the Liechtenstein Institute on Self-Determination at Princeton University. In 2002, he was appointed a Member of the Order of Australia (AM). In 2009, he was elected a Fellow of the Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia (FASSA).

Where do you see the most exciting research/debates happening in your field?

My own work covers several different fields, each with its own exciting dynamics. One of these areas is refugee studies, and there, some of the most innovative theoretical work has been concerned with the circumstances in which collective action problems, notoriously prevalent when one seeks cooperative solutions to refugee challenges, might be overcome. Here the work of Alexander Betts on suasion games and issue-linkages has played a very important role in exposing the difficulty of promoting regional solutions in response to refugee flows, a difficulty obvious both in Australia, and in Europe in the light of the 2015 refugee movements from Syria and Afghanistan. The other main area I cover is Afghanistan, and here by far the most exciting development has been the emergence of a new generation of Afghan scholars whose cutting-edge contributions can comfort an older generation of researchers with the knowledge that their area of research interest is in no danger of dying out.

How has the way you understand the world changed over time, and what (or who) prompted the most significant shifts in your thinking?

The most significant stimulus to a shift in my thinking about the world was the end of the Cold War and the collapse of communism as a serious model for how societies should be organised. The intellectual case against Marxism, and even more against Marxism-Leninism, had of course been mounted with great effect long before these events, and one can argue that Marxism as a credible philosophy did not survive the publication in 1978 of Leszek Kolakowski’s devastating trilogy Main Currents of Marxism. Nonetheless, it took the fall of the Berlin Wall fully to expose the bankruptcy of Soviet-type societies. But that said, once the Cold War was over, the role of the United States as a global power took on a different light, and the invasion of Iraq in 2003 highlighted the perils of the US’s shift, under the Bush administration, from a status quo to a revisionist approach to the world. Suddenly, being allied to the United States felt like engaging in bungee jumping without knowing the length of the rope. For me that feeling has persisted under the Trump administration

In your book What is a Refugee? you argue that refugees are a symptom of the state system. Do you feel that a structure of ‘us and them’ is inevitable in a state system that emphasises borders and sovereignty?

Yes, but what we understand by ‘them’ can have several meanings. There is no doubt that the rise of populism has fostered a decidedly non-cosmopolitan view of the world, but for some citizens within a territorial state, the particular focus of their Angst will not be everybody outside their borders, but simply those who seek to cross those borders and enter the state. The irony in this is that having borders is very different from having border controls. In the contemporary world there are vast numbers of uncontrolled borders, for example those separating different states of the USA. Borders of this kind serve to demarcate legal jurisdiction rather than provide a basis for the exclusion of those who are not residents of the particular state. Until relatively recently in human history, this was true not just of federal systems of government, but of the system of states more broadly. Border controls emerged in a very ragged and irregular fashion, and until the First World War it was possible to travel the world without a passport if one had the wherewithal to do so.

Is it possible for liberal states to achieve a politics built on human rights and cosmopolitanism amid the stark expansion of populist, anti-asylum regimes in the international system?

Yes, but it requires leadership, such as Angela Merkel sought to supply in Germany. One of the difficulties that arises when populist movements take shape is that more mainstream parties can embark on an unseemly competition to win back the votes of those who may have been tempted to move in a populist direction. Hostility to refugees and asylum seekers can be a relatively cheap way of doing this, since those who are targeted in this way rarely have the vote, and may not be supported by strong domestic constituencies poised to express outrage at the demonisation of those fleeing persecution or the threat of persecution. One only needs to return to the 1930s to realise that prevailing current hostilities to refugees represent nothing new. Some of the rhetoric that was deployed in western countries against Jews fleeing Nazi Germany can still send a shiver down one’s spine.

Why has it been so difficult for EU member states to find a cooperative, collaborative approach to asylum and the so-called European refugee crisis? Is a unified approach possible?

Given the constitutional structure of the EU, it is difficult to impose a solution on member states, and attempting to negotiate a solution then runs into significant free rider problems. The 2015 mass movements (of a kind with which African states are quite familiar) saw close to a million asylum seekers arriving in just two states, Greece and Italy. Faced with numbers of this kind, Greece in particular, struggling with its own domestic economic difficulties, had an overwhelming incentive to allow people to move on. Yet the ‘crisis’ was ultimately not one of numbers – even a million people do not amount to that many when one is talking about a continent with a population of over 500 million – but rather a political crisis of management and distribution in circumstances where domestic constituencies in many states were keen to avoid doing more than the absolute minimum in response to the refugee movements. That said, the ‘solution’ of warehousing refugees in Turkey is a very dangerous one, since large concentrations of refugees denied any hope of meaningful lives can be attractive recruitment areas for extremist forces looking for foot-soldiers.

To what extent do you feel the anarchic nature of the international system causes the ‘crisis’ of refugee crises; or is anarchy as Wendt famously put it “what states make of it”?

If the moral justification for a system of states, anarchic as it may nevertheless be, is that it gives rise to a protective responsibility between a vulnerable citizen and a protecting state, then refugees can be seen as the detritus produced by the imperfect operation of the system, either because states turn against their own, or because states prove incapable of protecting citizens from threats posed by other kinds of actors, such as militias or terrorist groups. Even in the event that the anarchy of the system could be mitigated to some degree by much denser networks of global governance, this problem would likely still exist, since it arises from the malevolence or incapacity of particular states.

Despite considerable media and political focus on the European refugee crisis, according to the UNHCR, 85% of the world’s refugees and displaced people are actually in what it considers developing countries. Will developed nations have to take on more responsibility in this area? If they continue to outsource the ‘problem’ to poorer, less stable states what will be the consequences?

Developed nations certainly should take on more responsibility; whether they actually will is another question entirely, since asymmetries of power give them a considerable capacity to resist pressures to do so. Nonetheless, the temptation to outsource the problem to poorer and less stable states is one to be resisted, since the perils associated with such moves are potentially considerable. If the stability of a poor country is put at risk by an unmanageable burden of refugees, resultant instability may have knock-on effects in the vicinity of the country and beyond, sufficiently adverse to raise serious questions about whether it was a good idea in the first place to leave such a country with such a burden.

In your latest book Transition in Afghanistan: Hope, Despair and the Limits of Statebuilding, you argue that for many Afghans “hope seems to have given way to despair.” What accounts for this shift? Which aspects of statebuilding efforts since 2001 do you see as the most damaging to Afghanistan?

Several factors have contributed to this problem. First, the high expectations of international involvement in Afghanistan that arose with Operation Enduring Freedom in 2001 dissipated fairly rapidly as US attention drifted from the Afghan theatre of operations to Iraq; as former US Defense Secretary Robert Gates noted in his memoirs, this had the effect of sucking oxygen out of the Afghan theatre at a crucial moment. Second, within Afghanistan under President Hamid Karzai, a neopatrimonial system emerged, in which formal institutions were entwined with patronage networks, leaving ordinary Afghans for the most part out in the cold and disengaged from a political order which they saw as serving sectional interests rather than addressing issues of concern to society as a whole. Third, in order to minimise the risk of Indian influence, Pakistan found it convenient to provide sanctuaries from which the Taliban and their associates could mount attacks against targets in Afghanistan, which over the last decade have killed more than 20,000 civilians, and created an atmosphere of extreme apprehension.

What future do you see for Afghanistan? Are there workable policy options that could significantly address Afghanistan’s problems?

The key to addressing Afghanistan’s problem is recognising the psychological dimension of the conflict. If ordinary people think that the Taliban will come out on top, they probably will, as it does not pay to be on the losing side in Afghanistan, and at critical moments people tend to shift their prudential loyalties to those whom they think will prove victorious. The main task for the Afghan government and its backers is to block developments that might give rise to this perception. The most important single step that could be taken would be effective pressure on Pakistan to shut down the Taliban’s sanctuaries. US pressure would be part of this story, but even more important is to engage China as a source of behind-the-scenes pressure, since Islamabad is more receptive to pressure from Beijing than from Washington, and depends upon China to provide crucial protection in the UN Security Council from criticisms that Pakistan might otherwise encounter.

What is the most important advice you could give to young scholars of International Relations?

I would offer three pieces of advice. First, never lose sight of the human and ethical dimensions of international relations. It is these that ultimately make the study of international relations worthwhile, even if they do not necessarily figure prominently in the minutiae of one’s research or scholarship. Second, try to master the complexities of the domestic politics of at least one state; this can protect one against excessively formalistic modelling that carries one far away from any notion of reality. Third, strive at all costs to write about complex ideas in language that is nonetheless accessible to people who may not be IR specialists. Specialist vocabularies can have their place, but there is little that I find more frustrating than struggling through a text so obscure that one begins to feel that Wittgenstein must have been wrong to deny the possibility of a private language!